WUNRN

https://www.devex.com/news/does-getting-pregnant-cause-girls-to-drop-out-of-school-85810

Schoolgirl Pregnancy & Education Dropout – Variables to Address for Specific Solutions

Investing the time and resources to understand the causes of

schoolgirl dropout in each setting will pay off with more effective

interventions. Photo by: Ashish Bajracharya / Population Council

By Stephanie

Psaki - 27 March 2015

Does pregnancy really cause girls

to drop out of school? Globally, “schoolgirl pregnancy” is cited as one of the

primary barriers to girls’ education. But the story may not be as simple as it

seems.

Yes, an adolescent girl’s formal

education is usually over the moment she becomes a mother. Laws and culture

often discourage girls from returning to school after giving birth. Unmarried

girls may be pressured to marry the father of the child. Married or not, having

a child can put an adolescent girl under intense financial strain. Finding work

might be the only way to provide for her young family. Going back to school may

feel impossible.

So how do we intervene? What can

be done to support adolescent girls — to help those who want to prevent

pregnancy and stay in school, and to help girls who give birth to continue

their education?

Before intervening, it’s

important to understand the different possible causes of school dropout. Is

pregnancy the only issue? Could there be other factors in a girl’s life that

make her both more likely to become pregnant and more likely to leave school

prematurely?

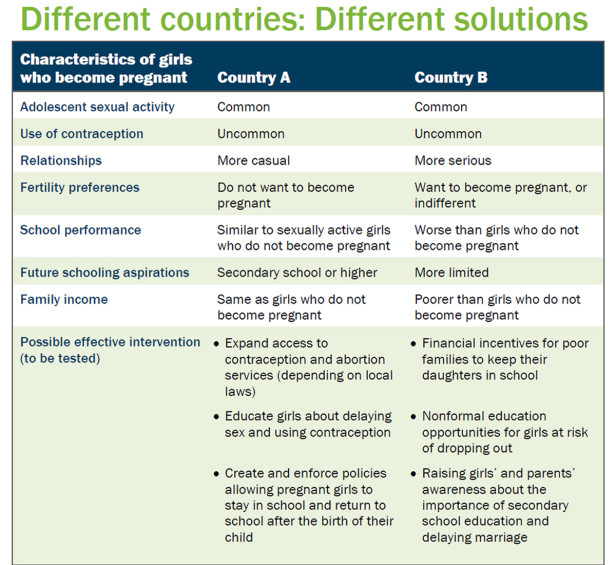

Picture two countries: We’ll call

them Country A and Country B. In both countries, 25 percent of girls have a

pregnancy before they leave school.

In Country A, premarital sex is

common and contraceptive use is low among adolescent girls; schoolgirl

pregnancies are usually unplanned. In this country, while girls who are

sexually active may differ from their peers who are not, girls who do become

pregnant are just like their sexually active peers who do not: They perform

just as well (or just as poorly) in school, they are just as likely to want to

continue on to secondary school, and their parents have similar incomes.

In other words, if these girls

had not become mothers, they would have remained in school as long as their

peers. The relationship between schoolgirl pregnancy and school dropout in

Country A is similar to patterns that Population

Council research has identified in parts of Malawi and Kenya.

In Country B, adolescent

schoolgirls are having sex, but usually in the context of serious relationships

or marriage. Among girls who are performing poorly in school, and come from

poorer households, pregnancies may be planned — or at least not actively

prevented. Their families may not put a high value on secondary education. They

may perceive fewer opportunities awaiting them if they continue in school.

For all of these reasons, girls

in Country B may well have dropped out of school prematurely even if they did

not become pregnant. The general patterns in Country B are more like what our

research has found in parts of Bangladesh.

The bottom line: In Country A,

pregnancy “causes” school dropout — because sexually active adolescent girls

who get pregnant are similar to peers who do not. In Country B, pregnancy is

not causing school dropout. The girls who are getting pregnant are doing worse

than their counterparts in other ways too.

Addressing schoolgirl pregnancy requires understanding country

contexts.

The solution to the problem of

schoolgirl pregnancy — and to school dropout more broadly — is not

one-size-fits-all. The cause — and remedy — will be different in different

situations. Investing the time and resources to understand the causes of

dropout in each setting will pay off with more effective interventions.

In Country A, effective

interventions would expand access to contraception and abortion services

(depending on local laws) for adolescent girls, including educating girls about

rights and gender norms, delaying sex and using contraception. Creation and

enforcement of policies allowing pregnant girls to stay in school and return to

school after the birth of their child may also improve girls’ education in

these settings.

In Country B, combating school

dropout would require interventions such as financial incentives for poor

families to keep their daughters in school, informal education opportunities

such as tutoring and girls’ groups for those at risk of dropping out, and raising

girls’ and parents’ awareness about the benefits of secondary school education

and delaying marriage.

First lady Michelle Obama and

other luminaries have called recently for bold and creative action to keep

girls in school and give them the opportunities they deserve. Championing

girls’ education is critical. But what’s necessary

for progress is to understand what’s threatening girls’

education so we can take the right measures to address these threats.