WUNRN

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/12/23/us/gender-gaps-stanford-94.html?_r=1

USA

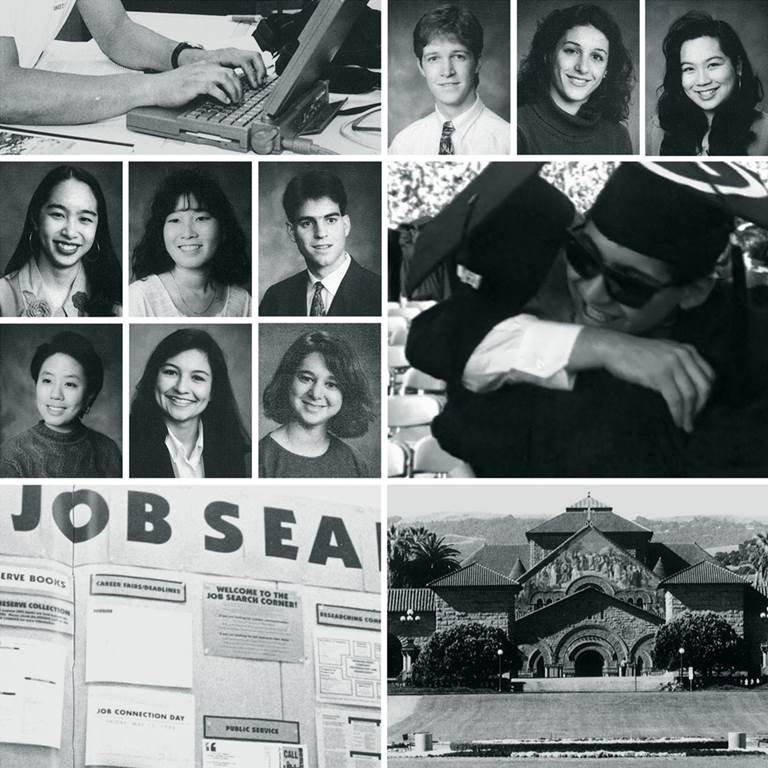

- STANFORD U – CLASS of 1994 – INSTEAD OF NARROWING GENDER GAPS, THE TECHNOLOGY

INDUSTRY CREATED VAST NEW ONES – 20-YEAR ANALYSIS

By JODI KANTOR DEC. 23, 2014

Palo

Alto, California - Instead of narrowing gender gaps, the technology industry

created vast new ones for Stanford University’s class of 1994.

In the history of American higher education, it is

hard to top the luck and timing of the Stanford class of 1994, whose members

arrived on campus barely aware of what an email was, and yet grew up to help

teach the rest of the planet to shop, send money, find love and navigate an

ever-expanding online universe.

They finished college precisely when and where the

web was stirring to life, and it swept many of them up, transforming computer

science and philosophy majors alike into dot-com founders, graduates with

uncertain plans into early employees of Netscape, and their 20-year reunion

weekend here in October into a miniature biography of the Internet.

A few steps from the opening party, the original

Yahoo servers, marked “1994,” stood at the entrance to an engineering building,

enshrined in glass cases like religious artifacts. Brunch the next morning was

hosted by a venture

capitalist who had made a key investment in Facebook. At a

football game, the alumni brandished “Fear the Nerds” signs and gossiped about

a classmate who

had recently sold the messaging service WhatsApp for over $20 billion.

“I tell people I graduated from Stanford the day

the web was born,” said another alumnus, Justin Kitch, whose senior thesis

turned into a start-up that turned into an Intuit acquisition.

The reunion told a more particular strand of

Internet history as well. The university, already the most powerful incubator

in Silicon Valley, embarked back then on a bold diversity experiment, trying to

dismantle old gender and racial barriers. While women had traditionally lagged

in business and finance, these students were present for the creation of an

entirely new field of human endeavor, one intended to topple old conventions,

embrace novel ways of doing things and promote entrepreneurship.

In some fields, the women of the class went on to

equal or outshine the men, including an Olympic gold medalist and the class’s best-known celebrity. Nearly half the

1,700-person class were women, and plenty were adventurous and inventive,

tinkerers and computer camp veterans who competed fiercely in engineering

contests; one won mention in the school paper for creating a taco-eating

machine.

Yet instead of narrowing gender gaps, the

technology industry created vast new ones, according to interviews with dozens

of members of the class and a broad array of Silicon Valley and Stanford

figures. “We were sitting on an oil boom, and the fact is that the women played

a support role instead of walking away with billion-dollar businesses,” said

Kamy Wicoff, who founded a website for

female writers.

It was largely the men of the class who became the

true creators, founding companies that changed behavior around the world and

using the proceeds to fund new projects that extended their influence. Some of

the women did well in technology, working at Google or Apple or hopping from

one start-up adventure to the next. Few of them described experiencing the

kinds of workplace abuses that have regularly cropped up among women in Silicon

Valley.

But even the most successful women could not match

some of their male classmates’ achievements. Some female computer science

majors had dropped out of the field, and few black or Hispanic women ever

worked in technology at all. The only woman to ascend through the ranks of

venture capital was shunted aside by her firm. Another appeared on the cover of

Fortune magazine as a great hope for gender in Silicon Valley — just before

unexpectedly leaving the company she had co-founded.

Dozens of women stayed in safe jobs, in or out of

technology, while they watched their spouses or former lab partners take on

ambitious quests. If the wealth among alumni traveled across gender lines, it

was mostly because so many had wed one another. When Jessica DiLullo Herrin, a

cheerleader-turned-economics whiz, arrived at the tailgate party, her

classmates quietly stared: She had founded two successful start-ups, a living

exception to the rule.

Not everyone was troubled by the imbalance. “If

meritocracy exists anywhere on earth, it is in Silicon Valley,” David Sacks, an

early figure at PayPal who went on to found other companies, emailed that

weekend from San Francisco, where he was renovating one of the most expensive

homes ever purchased in the city.

Without even setting foot back on campus for the

reunion, he was stirring up old ghosts. Because Stanford was so intertwined

with the businesses it fostered, the relationships and debates of the group’s

undergraduate years had continued to ripple through Silicon Valley, imprinting

a new industry in ways no one had anticipated. Mr. Sacks had fought the

school’s diversity efforts bitterly; those battles had first made him an

outcast among many of his classmates, and then sparked his technology career.

Every reunion is a reckoning about merit, choice

and luck, but as the members of the class of ’94 told their stories, that

weekend and in months of interviews before, they were also grappling with the

nature of the industry some had helped create. Had the Internet failed to

fulfill its promise to democratize business, or had the women missed the

moment? Why did Silicon Valley celebrate some kinds of outsiders but not

others?

“The Internet was supposed to be the great

equalizer,” said Gina Bianchini, the woman who had appeared on the cover of

Fortune. “So why hasn’t our generation of women moved the needle?”

When Stanford students of the early 1990s got

rejection letters, especially from banks and consulting firms, they often

posted them on the doors of their dorm rooms, as if to thumb their noses at

conventional notions of what they would achieve.

Even by the standards of the young and

Californian, their world felt open and new. Mikhail S. Gorbachev came to

campus, talked about sweeping away the Cold War and pronounced that “the ideas

and technologies of tomorrow are born here in California.” The front page of

The Stanford Daily featured a picture of Rachel Maddow, a campus activist

before she became a news host, locking lips with her girlfriend at a gay rights

march, then a startling sight.

The university retooled its curriculum and

residential life to prepare its students for a more diverse future. No one was

allowed to know the name of his or her freshman roommate before arriving on

campus, to prevent prejudgments based on ethnic names. In seminars by day,

students read texts by Aboriginal Australian writers; in the evenings, dorm

counselors held programs on black and feminist issues. With no iPhones, text

messages or even websites to distract them, students immersed themselves in

long discussions about how sexism had expressed itself in their families back

home or, in later years, about Condoleezza Rice’s policies as provost.

The first issues of Wired magazine were published

while they were undergraduates, capturing a spirit of optimism. “Life in

cyberspace seems to be shaping up exactly like Thomas Jefferson would have

wanted: founded on the primacy of individual liberty and a commitment to

pluralism, diversity, and community,” Mitchell Kapor, founder of Lotus,

would write in an

early issue.

So the residents of one dorm, Donner House, were

floored in the spring of 1991 to discover graffiti in their common room

reading, “If a woman says no, she means yes!” and “You’re all [expletive]

slaves.”

The graffiti, written by four students, caused an

uproar and led to a dorm-wide meeting. Afterward, David Sacks, an awkward

freshman who often had trouble looking other students in the eye yet showed a

flair for theatrical, cutting remarks, argued that the graffiti writers had

been treated unfairly. He made it clear that he found the graffiti itself

deplorable, calling it “sexist and violent,” in his first essay for The

Stanford Review, a conservative-libertarian campus newspaper.

But he also argued that an earlier round of

graffiti — including a crude statement about President George Bush — had been

just as offensive. A dorm discussion of the incident had a “mob mentality,” he

wrote. “Why was an apology demanded of the writers of the sexist graffiti,” he

asked, and not of the Bush slur?

Almost no one else in Donner House saw it that

way. “I remember David being stunned by the reaction” to his arguments, Adrian

Miller, his resident counselor at the time, said later.

Shunned by many of his dorm mates, Mr. Sacks made

a new home at The Review, which was founded by a law student named Peter Thiel

to critique what he saw as incessant political correctness. He and Mr. Sacks

saw themselves as relentless defenders of excellence, and they viewed the

university’s diversity efforts as its enemy, a clunky, top-down effort at

redistributing power. In the pages of The Review, they defined feminism in

negative terms — alarmist, accusatory toward men, blind to inherent biological

differences. Feminists “see phallocentrism in everything longer than it is

wide,” Mr. Sacks wrote. “If you’re male and heterosexual at Stanford, you have

sex and then you get screwed.” By his sophomore year, he was the editor of The

Review.

There were just a handful of women at The Review,

and some were peeling away. “I didn’t think I could stand up” to Mr. Sacks,

Samantha Hamlin, formerly Samantha Martinez-Colson, said in an interview,

adding that as a Latina she found the social penalty for being a writer there

to be too high.

Years later, in interviews, Mr. Sacks and Mr.

Thiel would emphasize The Review’s independence of spirit, its willingness to

take on the political correctness that more than a few classmates found

suffocating. “There was a creative contrarian ethos which encouraged rethinking

problems from first principles, and not just accepting the world the way it

was,” Keith Rabois, another former editor, said in an interview. But there was

an ugly side as well; Mr. Rabois left campus in 1992 after yelling “Can’t wait

until you die,” punctuating it with a homophobic slur. He said afterward that

he had been protesting campus speech codes.

Mr. Sacks was almost as abrasive, joking in print

about an imaginary course called “Bathroom Self Defense for Heterosexuals.” The

editors made easy fun of the excesses of Stanford’s diversity drive, but it was

not clear that they recognized the basic concerns of many female and minority

students — that they would not have the same opportunities as their white male

peers.

There was no time to waste. Before the Internet

era, most revolved around the “sole possession of a piece of technology that

was hard for others to replicate,” like a new kind of circuit, said John L.

Hennessy, the Stanford president and an engineer-entrepreneur himself, during

an interview over the reunion weekend.

But with the web, “all of the sudden we began

moving to a market where first mover advantage became enormous,” he said.

Connection speeds were growing faster, Americans were starting to shop online,

and multiplying e-commerce sites fought gladiatorial battles to control most

every area of spending.

Midway through the conversation, he paused. If the

dawn of the start-up era meant that consumer-oriented ideas were becoming more

important than proprietary technology, he asked himself aloud, shouldn’t more

women have flooded in?

“The natural inclination would have been, in the

consumer space, with a lower technical investment, a lowering of the threshold

for women to participate,” he said, sounding puzzled.

But there were still many hoops women had greater

trouble jumping through — components that had to be custom-built, capital that

needed to be secured from a small number of mostly male-run venture firms.

Ms. DiLullo blew past those limits; at 24, she

threw herself into an idea for an online gift registry. When she and her

business partner met with one venture capitalist, he looked at them and said,

“I see the pretty girls. Beyond the pretty girls, what do you have for me?”

They ignored the slight, took his money and dropped out of Stanford Business

School to start their company, Della & James, which competed with

WeddingChannel.com and then merged with it, riding the wave of the dot-com

boom. In 1999, Ms. DiLullo appeared on “The Oprah Winfrey Show” as a can-do

example of female entrepreneurship. Hundreds of women contacted her in the

weeks after, wanting to know how they could start businesses, too.

But a year later, the dot-com bubble burst,

leaving Silicon Valley so despairing that some classmates remember the local

U-Haul companies running out of trucks. The bust had come right before their

30th birthdays, just as many of them were looking for stable jobs that could

accommodate marriage and children.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

A Slow Slide for Women in Technology

The share of women working in technology

dropped after the sector collapse in 2000. Although the sector recovered,

participation by women is lower than in 1998.

Change

1998-2013 in % of women in the technology sector. Change from

1998-2013 in % of technology managers who are women.

Source: U.S. Equal Opportunity Employment Commission

Even Ms. DiLullo retreated. She wanted to start

companies, not work for them. But WeddingChannel.com had become a big

organization with three co-founders, and she and her new husband, Chad Herrin,

wanted children, which she could not reconcile in her mind with a dot-com life.

So the class’s most prominent female entrepreneur moved back to Austin for her

husband’s career and took a safe corporate job at Dell.

David Sacks, on the other hand, was unmarried and

unencumbered, and in 1999 he left politics, his law degree and a job at the

consulting firm McKinsey & Company to join his Stanford Review friends at a

technology start-up, because of “the desire to live on the edge, to fight an

epic battle, to experience in a very diluted way what previous generations must

have felt as they prepared to go to war,” he wrote at

the time. For his generation, he wrote, “instead of violence, unbridled

capitalism has become the preferred vehicle for channeling their energy,

intellect and aggression.”

Led once again by Peter Thiel, the men had found a

new way to translate their libertarian impulses and hatred of bureaucratic

impediments: They wanted to create an alternative to the monetary system, but

they settled for an electronic payment method that bypassed banks. They would

go on to call their vision PayPal, and it provided Mr. Sacks with the war he

craved: The new service fought competitors, regulators and Russian hackers who

stole tens of millions of dollars.

PayPal had a hard time hiring women, Max Levchin,

another co-founder, later told a class at

Stanford, “because PayPal was just a bunch of nerds! They never talked to

women. So how were they supposed to interact with and hire them?”

“The notion that diversity in an early team is

important or good is completely wrong,” he added. “The more diverse the early

group, the harder it is for people to find common ground.”

Later, in an interview, Mr. Levchin said he had

been speaking about diversity of programming backgrounds, not race or gender.

But intentionally or not, he stated something many people quietly believed: The

same thing that made Silicon Valley phenomenally successful also kept it

homogeneous, and start-ups had an almost inevitable like-with-like quality.

The kind of common ground shared by the early PayPal

leaders “is always the critical ingredient on the founding teams,” Mr. Thiel

said in an interview. “You have these great friendships that were built over

some period of time. Silicon Valley flows out of deep relationships that people

have built. That’s the structural reality.”

Later, well after Mr. Sacks, Mr. Thiel and their

crew had weathered the dot-com crash, conquered the hackers, beat the

competitors, taken the company public and then sold PayPal to eBay in

2002 for a billion and a half dollars, Mr. Sacks called the company “the

template for the modern Silicon Valley start-up.” Less than 10 years after

graduation, he and Mr. Thiel had been transformed from outcasts into favorites

with a reputation for seeing the future. Far from the only libertarians in

Silicon Valley, they had finally found an environment that meshed perfectly

with their desire for unfettered competition and freedom from constraints. The

money they made seemed like vindication of their ideas.

“Those who win get to rewrite the history,” said

Fred Turner, a Stanford historian of technology.

The success of the struggle to create PayPal, and

its eventual sale price, gave the men a new power: the knowledge to create new

companies and the ability to fund their own and one another’s. Billion-dollar

start-ups had been rare. But in the next few years, the so-called PayPal Mafia

went on to found seven companies that reached blockbuster scale, including

YouTube, LinkedIn, Yelp and a business-messaging service called Yammer, founded

by Mr. Sacks and sold a few years later to Microsoft for $1.2 billion.

At the time of the sale, Yammer’s executive team

was half female. The harshness of the Stanford Review crowd’s old arguments was

largely forgotten; Mr. Rabois, who had once yelled the homophobic slur, and Mr.

Thiel had come out as gay.

Mr. Sacks said in an email that he was

“embarrassed by some of the things I wrote in college over 20 years ago, and I

am sorry I wrote them,” adding that he was “horrified” by his old views on

homosexuality and that he calls himself a supporter of gay rights and marriage

equality. “These views do not represent who I am or what I believe today,” he

said.

But Mr. Sacks did not entirely lose his touch for

provocation. For his 40th birthday, just after the Yammer sale was announced,

he threw himself a Marie Antoinette-themed bash, shipping cakes as invitations,

hiring the rapper Snoop Dogg to perform, and appearing at the party in

head-to-toe 18th-century French court dress.

The next chapter of Jessica DiLullo Herrin’s

career unfolded in a kind of alternate Silicon Valley reality in which venture

capital firms don’t figure much, like-minded women start companies together,

and innovation unfurls on a new-mother-friendly schedule.

She deliberately started low-key, driving around

Texas in 2004 with a car full of wires and glass beads, asking friends to host

“trunk shows” where they could make their own jewelry. (“It’s easy and

rewarding to host a Luxe Jewels party,” her fliers said.) Her real goal was to

update the direct-sales industry — like Mary Kay makeup or Tupperware parties,

transformed for the Internet age. But she was also pregnant with her first

child, so instead of relying on venture capitalists who would impose a firm

timetable, she funded the new business with her own money and the revenue that

began trickling in so no one else would control her schedule. (She later relied

on investors to expand the company.)

She let the project slow for a time after she gave

birth and then picked it up again, eventually switching to premade costume

jewelry. Once her second daughter, Tatum, reached 6 months old in late 2006,

she recruited the rest of the initial team.

“When we reached a million in revenue, I stopped

breastfeeding,” she said.

Her company was nearly as homogeneous as Paypal,

stacked with female Stanford graduates interested in business and fashion.

“O.K., who is in?” she asked her college girlfriends. At a Stanford reunion,

she met a jewelry designer who became her partner, and they renamed the company

after their grandmothers: Stella & Dot.

But it was not precisely a Silicon Valley company.

Ms. Herrin was giving sellers their own web pages and using Facebook to

showcase goods, not trying to create a new device or software.

“I’ve never tried to sit at the boys’ table,” she

said.

That may have been the safer bet. Of the tiny

number of 1994 women who were starting and funding more technology-centric

ventures, two were having a bruising time. Gina Bianchini had a sense of hustle

and ambition similar to Ms. Herrin’s, also attended Stanford Business School,

and also co-founded a company in 2004. Called Ning, it allowed people to create

their own networks organized around specialized interests, like the “Twilight”

franchise or working at I.B.M. Her co-founder was the Netscape founder Marc

Andreessen, and together they took on over $100 million in funding. Ms.

Bianchini was called a “Web 2.0 Hottie,”

and Fortune featured her on the cover as one of “The New Valley Girls.”

“She never, ever, would have founded a company

about weddings,” said Kamy Wicoff, her classmate. But one day in 2010, her

college friends got a text from her saying she was leaving unexpectedly, and

soon Mr. Andreessen had sold the company. Some classmates whispered that she

had only gotten the chance to co-found the company because the two had once

dated — even though work and personal lives often overlapped in close-knit Silicon

Valley.

Another woman from the class of 1994 was quoted in

the Fortune article:Trae

Vassallo, who was Traci Neist when she built the taco-eating machine

all those years ago, attended Stanford Business School with Ms. Herrin and Ms.

Bianchini, co-founded a mobile device company, and then joined Kleiner Perkins,

a premier venture capital firm. Ms. Vassallo did well, eventually playing key

roles in two of its most successful deals

of 2014, including the sale of Nest Labs, a maker of networked home alarms and

other devices that was acquired by Google for $3.2 billion.

But in early 2014, Ms. Vassallo was quietly let

go. The firm was downsizing over all, especially in green technology, one of Ms.

Vassallo’s specialties, and men were shown the exit as well. But in interviews,

several former colleagues said it was far from an easy environment for women,

with all-male outings and fierce internal competition for who got which board

seat — meaning internal credit — for each company, not to mention a sexual discrimination lawsuit filed

by a female junior partner, scheduled for trial in early 2015.

They also said that Ms. Vassallo,

earnest and so technical that she started a robotics program at a local girls’

school, had not been as forceful, or as adept a politician, as some of her male

peers. If that was the case, the irony seemed cruel: She had just the kind of

engineering background that everyone was always saying more women needed, but

lost out, in effect, for being too much of a geek.

Kleiner Perkins said that gender did not play a

role in Ms. Vassallo’s departure and that 20 percent of its partners were

women. “We very much value Trae’s contributions to the firm, and we continue to

have a strong relationship with her,” a spokeswoman said. Ms. Vassallo declined

to comment.

Her departure became a source of frustration among

women in her field. “A travesty,” Ann Miura-Ko, a fellow venture capitalist,

called it in an interview. Since 1999, the number of female partners in venture

capital has declined by nearly half, from 10 percent to 6 percent, according

to a recent Babson College study.

By that time, Ms. Herrin, Ms. Vassallo’s

classmate, was getting ready to attend the 20-year reunion. She had annual

sales of over $200 million in six countries; tens of thousands of stylists, to

whom she had paid out hundreds of millions of dollars in commissions; and the

beginning of an expansion into other products.

The frenzy had an unlikely effect on the some

members of the Stanford Review group: They were becoming cheerleaders for women

in technology, not for ideological reasons, but for market-based ones.

“Conservatives must acknowledge their role to expand the free labor market and

kindle social progress by championing female technologists,”wrote Joe

Lonsdale, another former Stanford Review editor and the co-founder of Palantir,

a data analysis company, in The Review a week before the reunion. Like many

others, he was finding that the biggest obstacle to starting new companies was

a dearth of technical talent so severe they worried it would hinder innovation.

“Everybody here has a huge incentive to get all

the talented people we can, and that includes 50 percent of the population,”

said Mr. Sacks, who a few weeks later joined and invested in a fast-growing start-up whose

employees were 40 percent female, high by industry standards.

The real surprise of the reunion weekend, however,

was that more of the women in the class of ’94 were finally becoming

entrepreneurs, later and on a smaller scale than many of the men, but founders

nonetheless.

The rhythms

of their lives and the technology industry were finally clicking: Companies

were becoming easier to start just as their children were becoming more

self-sufficient, and they did not want to miss another chance. Their young

companies matched technology

companies with freelance legal talent; displayed art and

photography on flat-screen televisions; and made electronic wristbands that

enabled parents to keep track of children playing outdoors.

Some of the

female doctors in the class, ambitious yet risk-averse in their choices two

decades ago, were taking the leap, too, founding companies that sold

custom-blended vitamins online and helped monitor patients with chronic diseases.

Dr. Dayna Long, a pediatrician, created a web-based screening tool to identify invisible

factors that sapped patients’ health, like hunger and unsafe living conditions.

When she pitched the idea to start-ups, requesting pro bono technical help, she

was almost always the only black woman in the room. She was not an

entrepreneur, but she had a vision for a new way to use technology, which she

had persuaded hospitals across the Bay Area to adopt.

As the

reunion weekend drew to a close, Gina Bianchini sat down with Arielle Miller

Levitan, the physician who co-founded the vitamin site, and a laptop to coach

her on everything from font size to funding. Within a year of leaving Ning, Ms.

Bianchini had started over, with her own company, named Mightybell.

The way to prevail, she felt, was to be resilient, to risk failing twice, to

pursue her years-old vision about connecting like-minded people and refine it

until it was exactly right.

“Silicon

Valley loves redemption. So do I,” she said.