WUNRN

http://us4.campaign-archive1.com/?u=5d5693a8f1af2d4b6cb3160e8&id=7c2cd8c3fa&e=1e22dbc3a0

Direct Link to Full 84-Page 2014 Mali FGM Report:

http://www.28toomany.org/media/uploads/mali_final.pdf

With Mali in Political Turmoil,

High FGM Rates Persist

By Dulcie Leimbach - Nov 20, 2014

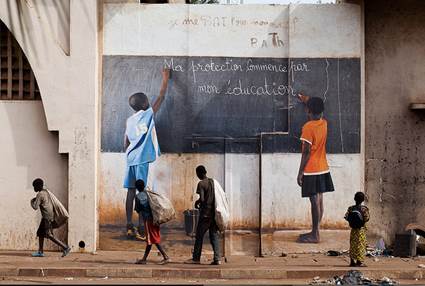

As part of a campaign tackling violence

against women, including the practice of excision, in Mali, various photo

exhibitions, “From Shadow Into Light,” above, were presented by Oxfam

International and other groups in 2013. VINCENT TREMEAU

BAMAKO, Mali — In the primarily Francophone

and Anglophone region of West Africa, Mali is said to have one of the highest

rates of female genital mutilation, with about 91 percent of girls and women

having undergone the circumcision — a rate that has not only stayed stubbornly

high but may also be inching upward. Younger females are also being subject to

the procedure — cutting of their genitalia — starting at infancy.

The political impetus to ban the practice

is severely lacking, say experts in Mali and elsewhere. The only country in

West Africa that may claim higher prevalence rates, studies suggest, is Guinea,

while Sierra Leone and Gambia closely compete with Mali in percentages. The

practice is common in Burkina Faso, Guinea-Bissau and Liberia as well.

A new report

on Mali produced by a private charity in Britain, called 28 Too Many, said that

the prevalence of female genital mutilation, or FGM, has not decreased in the

last 20 years and that the estimated rate among women and girls, aged 15 to 49,

was 91.4 percent in 2013.

The report noted that the 2013 survey did

not include northern Mali, which is politically rocky, so it concluded that the

rate has not changed much in the last decade. The charity took its name from

its original attention on the 28 countries in Africa where certain communities

practice FGM, although it is now widely known that the practice occurs in parts

of the Middle East and Asia as well. (In Egypt, which bans the practice, the

father of a girl who died from the procedure was on trial recently as was the

doctor who did the surgery; both were acquitted.)

One main obstacle in getting Mali to

abandon the practice is the lack of legislation prohibiting excision, as it is

called in French-speaking African countries. Gambia and Sierra Leone have no

legal bans against the practice, either, said Louise Robertson, the

communications manager for 28 Too Many, based in London.

The low priority on passing such a law in

Mali, despite past motions, reflects the lingering side effects of the

political turmoil that struck the country in 2012 and continues today, making government

attempts and commitments by nonprofit groups to improve conditions for women a

huge struggle.

Mali was at one point on a legal track to

fighting the practice of excision, having ratified several international

conventions focused on the well-being of women and girls, including the

Convention to Eliminate All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, or Cedaw.

But a draft law banning excision has been sitting in the General Assembly since

2009. (Only 10 percent of parliamentarians are women.)

The challenge could not be more formidable

in a country that legally requires a woman to obey her husband. News of Ebola

cases now hitting Mali could put promotion of the rights of girls and women

behind further, given that the health ministry, woefully inept, must contend

with containing the disease.

“It’s definitely a difficult conversation

where it’s still legal with the government,” said Jennifer Melton, a child

protection specialist with Unicef,

referring to excision. She was interviewed this summer at the agency’s sunny,

open compound in the Cité des Enfants neighborhood of Bamako, not far from a

rickety old amusement park of the same name.

Although Mali has ratified international

treaties that prohibit excision, it has yet to conform to FGM and early

marriage provisions in the pacts. The government has an action plan addressing

the issue through a program in the Ministry of Women, Children and Family, but

the action plan expires this year and a new one is to be drafted. Melton said

it could enable better coordination on fighting excision, though not

necessarily ban it.

Besides the political crisis, involving a

coup in 2012 and a takeover by jihadists in the north, who remain entrenched in

spots, an influx of refugees fleeing from the north to the south of Mali has

apparently led to increased numbers of females undergoing excision.

Traditionally, the north, inhabited mainly

by Tuaregs, did not practice female genital mutilation, but refugees now living

in Bamako and the outskirts find themselves facing new cultural traditions. The

pressure for women and girls to be accepted in their new communities (and

marry) can mean following local customs like cutting.

“There is concern and risk that more girls

are being cut from people who moved to the south from the north,” Melton said,

adding that the displaced people do not intend to go back home soon, aware of

rising attacks in the north. (The UN’s peacekeeping mission in Mali has been a

repeated target, with 32 peacekeepers killed, mostly in the north, since the

mission was deployed in July 2013.)

Even when a country passes a law banning

excision, it does not mean the ritual vanishes, as in the case of Egypt. Many

countries in West Africa try to end the practice — if the political will exists

— in various ways, like stressing the human rights of women and girls;

emphasizing the damning health effects, including depression and fatal

infections; and offering the excisors, or women who do the cutting, new lines

of work.

The 28 Too Many report described how the

ritual is done in the village of Sikasso, Mali, for example. Young girls who

undergo cutting are washed afterward in a liquid of ebony tree leaves, followed

by cooled ash to stop the bleeding and then wrapped in applications of shea

butter to aid healing.

Lamine Boubakar Traoré, a program

specialist for the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) in Bamako, said in an interview at his

office in August, located in a neighborhood near the American embassy, that

meeting with new parliamentarians to discuss a legal ban has been slow, and a

“majority of the population is still for FGM.”

One of the Oxfam photo campaigns, focused

on women, in Bamako, the capital. The prevalence rate of female genital

mutilation in Mali, considered a form of violence, is stuck above 90 percent.

VINCENT TREMEAU/OXFAM INTERNATIONAL

Traoré noted that the population supported

excision because most of the country is Muslim, and they say the tradition is

Islamic. “It is not true, but it is very difficult for our parliament to pass a

law,” as such a law would mean a stand against religion.

“The main strategy is to have discussions

with religious leaders,” Traoré said, which is problematic in Mali, as “our

political leaders are afraid” of challenging such people. “We have many

sessions with religious leaders, but they already refused to talk about law.

They say it is God’s recommendation.”

Mali, he said, is a patriarchal society,

and “women have no power to stop it.”

Traoré and his colleagues will still work

with communities directly, he added, noting that “if a community wants to

change, the religious leaders will change too” – and that “if you continue to work

with communities, more and more people banish FGM.”

That is not a sure bet in villages where

religious leaders — primarily imams — insist that excision is integral to their

culture. If an entire village accepts the practice, it is difficult to persuade

one family to say no.

“They [religious leaders] also say we can’t

marry a women that is not cut — the status of men will go down if they have sex

with a woman who has not been cut,” Traoré, who is Malian, said.

Yet programs to ban excision go on, albeit working

largely in silos, to Melton’s dismay, she said, because of the political

crisis. Each program, whether it is done by a private charity or by a UN

entity, approaches the issue differently, with varying degrees of success, if

any.

Getting everyone on board takes major

coordination, a hurdle in a country that operates with little urgency and lacks

extensive networks of paved roads. Government goals to tackle the issue seem

muddled, Melton said, though she expected efforts to start again nationally with

Unicef and the UN Population Fund.

“Lots of stuff is going on, but it’s

difficult to say with 100 percent confidence that there’s a real concerted

effort,” she said of work by the government as well as by other organizations.

(As an example of the silo effect, a top UN official at the peacekeeping

mission in Mali was unaware of the high rates of excision in the country.)

About 1,000 villages have walked away from

excision, Melton said, a tally counted through public declarations, although

the true geographic picture is not precise, so mapping needs to be done to

clarify which villages have actually dropped the practice. It takes years to

achieve community abandonment, and what wins in one village does not always

translate into another.

Unicef takes a collective abandonment

approach to its program work on excision. Melton and her colleagues are engaged

in about 100 communities and begin by identifying a village where the chief is

amenable to broaching the topic and some rapport can be built. Such “change agents”

and communities with strong grass-roots groups are often important candidates

for cultural shifts. Not every religious leader is amenable, so coming on

strong can backfire, Melton said.

After she and her colleagues talk with the

chief, the larger community is targeted next. Sometimes, a cluster of villages

with social or economic ties may have similar value systems and social norms,

like intermarrying, presenting strategic opportunities to ending excision on a

wider scale.

Moving along in the discussion, excisors

also need to be convinced to put away their razors for other livelihoods.

Mothers must be certain that ending the practice will not affect their

daughters’ marriageability. Youths — boys and girls — need to support

abandonment, too.

Nearly every villager might need to be

reassured that the practice has nothing to do with Islam or any other religion,

so they are not breaking doctrine if they forgo excision.

Sometimes, the mere mention of pleasure —

that it’s all right for women to enjoy themselves during sex — wends into the

anti-FGM narrative. (Often, the rationale for cutting is to remove women’s

sexual desire and the possibility of her straying to another man or losing her

virginity too soon.)

Despite reams of UN and other major studies

delving into female circumcision, little is said about its effects on a woman’s

ability to orgasm. Melton and Traoré suggested it depends on the type of

excision — from a nick of external genitalia to more invasive measures.

When asked if excision interferes with a

woman’s sex life, Traoré said, “Absolutely.”

“If a girl is not cut before marriage, her

husband knows,” he said. “He will tell the parents: Take your daughter, have

her cut and then return her. I can’t have sex with your daughter because she

hasn’t been cut.” He added that the woman who is not cut is viewed the same as

a man, as having a penis.

Complicating matters, he said, women agree

to be cut because they believe men don’t like them without excision.

In villages, dialogue between men and women

is sparse, so Unicef programmers hold separate discussions on traditional

lines, discovering that men think women want to keep the tradition and women

think men revere it, a paradox that gives anti-FGM programmers a chance, Melton

said, to “break the misunderstandings about each other.”

When 80 percent of the community finally

endorses abandonment, a public declaration is announced and celebrations are

held. Follow-up discussions continue with village leaders — on prevention,

change and health matters — coupled with activities like theater skits. Indeed,

the dialogue may never stop — with the change agents meeting in small and large

groups, a mix of men and women. But smaller groups are generally preferred for

talk about the nitty gritty — reproductive organs, sexuality — in separate

gender groups.

“It’s taboo to discuss anything related to

sex in mixed companies,” Melton said. Some talks will use anatomically correct

drawings or wooden dolls to show the effects of cutting on female external

organs.

Once abandonment takes hold, talking about

excision flows more freely. “Now they can express their feelings about it; it

means people are thinking about it,” Melton said.

Success in villages beyond the capital has

not influenced hearts and minds there, however, as reports — many anecdotally

based — of infants being cut have been circulating in the last year.

Fifteen to 20 years ago, excision was done

on older girls, but the practice is apparently moving to newborns and toddlers.

This development appears to have sprung up to avoid arguments with older girls

who rebel against being cut. Some practitioners also think that the sensation

of pain is minimal at infancy, yet there is no proof of that.

Traoré said that in Bamako, 84 percent of

people practice excision, compared with Timbuktu, where it is less than 10

percent. The surgery occurs in unsanitary conditions, like toilets, possibly

because health ministers have taken steps to banish the practice from occurring

in hospitals and health centers.

The increase of babies being cut is a

phenomenon not counted in current statistics, since the surveys are done with

women and girls aged 15-49, so it will take another 15 years to incorporate the

new numbers, Melton said.

She expressed optimism about long-range

successes to banning excision. With a new government in place — Ibrahim

Boubacar Keita was voted into the presidential palace in 2013 — it is time for

Mali to move forward, as “things are now in place.”

Yet more recently, with Ebola rearing its deadly head in Bamako and some jihadists in the north unwilling to negotiate a peace treaty with the government, it hardly seems possible that Mali will move ahead on ending excision.