WUNRN

Slumping

Fertility Rates in Developing Countries Spark Labor Worries

Elderly people, above, at a

health center in rural

By JAMES

HOOKWAY –

March 10, 2014

BAAN TAM TA

KEM,

Birthrates

have fallen in

Out here among

the green rice fields and plantations of rural

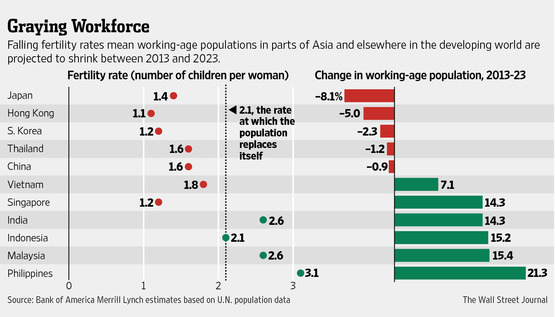

Other pockets

of the developing world also have seen sharp declines in fertility rates,

including

"Aging is

occurring nearly everywhere, and it's happening faster than many people

think," says Babatunde Ostimehin, executive director of the United

Nations' population program. "If governments don't respond, they could end

up facing a crisis."

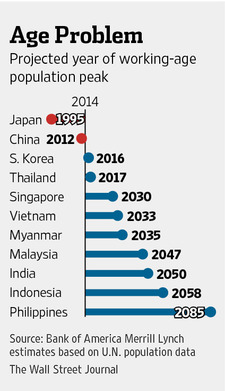

Demographers

such as Michael Teitelbaum at Harvard Law School and Jay Winter, a history

professor at Yale University, note that already more than half the world's

population lives in aging countries where the fertility rate is less than 2.1

children per woman—the rate required to replace both parents, once infant

mortality is taken into account.

This is both

an opportunity and a threat. On one hand, it could help preserve natural

resources in nations that have been taxed by rapid population growth. But some

economists blame a slowdown in population growth for contributing to such

disparate events as the Great Depression and

Some developing

nations that built their economies on an expanding supply of young people

entering the workforce are rethinking their growth plans.

Chile's

government last year announced plans for a "baby bonus" for parents

who have a third child, following the lead of countries such as France and

Australia, which already have incentives for parents to have more children.

Fertility

rates rise and fall. The improving economy in the

In the

developing world, fertility rates are likely to continue falling. More people

are moving to crowded megacities where housing and education are increasingly

expensive, and the cultural changes sparked by these migrations are difficult

to reverse.

"

In

Retirees make

up a significant and visible proportion of the demonstrators who regularly take

to the streets in

"There

are a lot more of us now, and we have a voice," said Suchakree Somkong, 74

years old, waving a yellow royal banner with his friends at one recent protest.

"This is old-people's power."

Younger Thais,

meanwhile, are struggling to makes ends meet even as unemployment rates remain

consistently low. For many, having more children—or any at all—isn't going to happen

soon.

Angsana Niwat,

38, moved to

"If you

want to work, you need to find somebody and pay them to look after the

kids," says Ms. Angsana, who no longer works. "Then you have to think

about paying for extra tuition to make sure they get into a good university.

It's a struggle to make ends meet." She is dipping into her savings from

her old job in public relations, she says, because her husband's business

installing mirrors barely pulls in enough money to cover mortgage payments.

Some academics

such as Therdsak Chomtohsuwan, an economics professor at

In rural

villages, community leaders are trying to devise ways to cope with the changes.

In Baan Nong

Thong Lim, a 35-year-old monk at the local Buddhist temple began teaching

elderly villagers last July how to adjust to life with fewer young people

around to care for them. The monk, Phra Weera Sripron, gave lessons on how to

coax lime trees to yield fruit all year round by constraining their roots in

upturned cement pipes, and how to grow mushrooms, a cash crop, in homemade,

darkened gazebos.

"At the

same time we teach them about self-sufficiency and other Buddhist

principles," says Phra Weera, who sports close-cropped salt-and-pepper

hair with his saffron robe. "There are many more people coming in to the

temple now."

Local

villagers agree. "When we came to the temple before, we would just

contribute merit for the next life," says Sanit Thipnangrong, a

58-year-old grandmother. "But by doing this, we can improve our prospects

in this life and not wait around for anybody else to help us."

Some Thais

contend that rather than trying to persuade people to have more children, the

nation needs to figure out how to make do with fewer.

Mechai

Viravaidya, a veteran health campaigner, picked up the nickname "Mr.

Condom" in the 1980s when he launched a program to encourage Thai women to

have fewer children and to protect against AIDS. He traveled the country

teaching the proper use of contraception to nudge down birthrates and improve

living standards.

"People

aren't going to start having more children," he says. "That horse has

already left the stable. What we are doing here is teaching elderly people in

rural communities to learn more, earn more and increase their own

productivity."

To that end,

Mr. Mechai founded the

The goal is to

teach Thai youngsters—and their parents, grandparents and guardians, who drop

in frequently—how to produce more. Lecturers from nearby colleges stop in

regularly to tell students how to find markets for their products and earn

cash. Mushrooms and bean sprouts are potentially big earners, Mr. Mechai says.

"The yield on bean sprouts is 700%," he says. "That's better

than marijuana."

The school

also aims to redress some of the shortcomings of the country's education

sector. In last year's Program for International Student Assessment tests, run

by the international Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development,

Thailand, with a per capita income of just over $5,000 a year, lagged far

behind competitors such as China, South Korea and Singapore, ranking 48th of

the 65 countries participating.

In the nearby

A decade ago,

the area was mostly thick jungle. But now land has been cleared to raise a

variety of crops, including limes and orchids. The villagers also produce local

delicacies such as crickets fried with rock salt and fiery chili peppers, and

homeopathic remedies such as pillows stuffed with herbs that they sell as far

away as

Prisoners at a

nearby jail were taught new agricultural techniques while in detention, and

police chief Col. Narongchit Maneechote put his latest batch of recruits from

the police academy to work digging out weeds and planting saplings on the

police station's grounds.

"When

people used to see police officers with some extra money, they thought we were

getting it from protection rackets for illegal lotteries," Col. Narongchit

said. "Now they know it comes from farming."

Such self-help

programs are small steps. "But it's getting closer to the answer,"

says Mr. Therdsak of

In Hua Ngom, a

village of about 6,000 in Chiang Rai province in

"At first

we thought it was something to do with the crisis," says Mr. Winai,

referring to the Asian financial problems in the late 1990s that threw

One

73-year-old woman, he recalls, flung herself down a water well. "She

wasn't poor," he says. "She was wearing several gold necklaces. But

deep down she was overcome by the pressure of living on her own."

There have

been no suicides in recent months, he says, as older residents learn about home

farming and study languages such as English. But birthrates remain stubbornly

low. Last year, only three children were born in Hua Ngom.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________