WUNRN

FOR YEARS, WITH HOPE & HEARTACHE, WOMEN SEARCH FOR THE MISSING, THE

VICTIMS OF ENFORCED DISAPPEARANCES

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Link to Full

UNArticle: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=14970&LangID=E

INTERNATIONAL DAY OF THE VICTIMS OF ENFORCED DISAPPEARANCES - 30 AUGUST

REMOVE ALL

OBSTACLES TO AID INVESTIGATIONS ON FATE OF DISAPPEARED PERSONS

GENEVA (30 August

2014) –Two United Nations

expert groups on enforced disappearances call on States “to remove all

obstacles” to aid investigations into the fate of disappeared persons.

On

the International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances, the Committee

on Enforced Disappearances and the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary

Disappearances urge Governments to support relatives of the disappeared by

removing all obstacles hindering their search for loved ones, including through

the opening of all archives, especially military files.

“More

than 43,000 cases, the majority dating back decades, remain outstanding with

the United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances.

These cases stay open for several reasons, often because relatives have no

support in finding out what happened.

The

search for disappeared family members and, in many cases, the identification of

discovered remains, is always the most pressing request of relatives who endure

tremendous suffering in their long wait to know the fate or whereabouts of

their loved ones. Many relatives face unjustified hurdles in their search, due

to the lack of political will, or insufficient and inadequate

investigations......

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

http://www.ipsnews.net/2012/05/no-celebration-for-mothers-of-the-missing-in-mexico/

"Where are they?" ask mothers looking for their missing sons

and daughters.

Credit:Daniela Pastrana/IPS

MEXICO

CITY, May 15, 2012 (IPS) - Emma Veleta and Toribio Muñoz were married 40 years

ago and had seven children, four boys and three girls. They lived in the town

of

Armed men

wearing federal police uniforms stormed into their house and took away Muñoz, a

retired railway worker, and all of his sons, a nephew, a son-in-law, and a

grandson. Veleta has never seen them again.

"I

thought that if I came to

Guadalupe

Aguilar, a retired nurse, is also searching for a missing loved one: her son José Luis. The

last she knew of him was on Jan. 11, 2011, when the 34-year-old went to meet

his brother in the city of

"It

was a 12-minute drive, but he never got there. His car turned up later in

Colima (a neighbouring state)," said Aguilar, who on Sept. 7 managed to

speak to President Felipe Calderón when he visited Guadalajara, and asked him

for help finding her son.

Calderón

"told me to go to the Procuraduría de Víctimas (

Veleta,

Aguilar and many other women in this country did not celebrate on May 10, which

is Mother’s Day in

"We

came (to the capital) to remind

The first

group of women set out on Monday May 7 from violence-stricken cities in

After a

2,000-km drive, they reached the capital on Wednesday May 9, where they met

with the mothers who have come together in the Committee of Relatives of Dead

and Missing Migrants of El Salvador (COFAMIDE), which has documented 319 cases

of Salvadoran migrants who have gone missing in

On Friday

May 11, they met with Attorney General Marisela Morales to express their main

demands: federal investigations and an immediate search for all of the missing

persons, as well as the creation of a national database on cases of

disappearance, a special prosecutor’s office on disappearances, and a federal

programme to assist the families of victims.

They also

called for the implementation of a protocol on the procedures to be followed in

investigations of disappearances, and of United Nations recommendations in

cases of forced disappearance.

The

interior minister, Alejandro Poiré, cancelled the meeting the mothers had

scheduled with him.

"Where

are they?" the mothers-turned-activists ask at every door they knock on.

In the

caravan, they were accompanied by members of HIJOS, an organisation made up of

the sons and daughters of victims of forced disappearance of

"Don’t

lose faith," they were told by Senator Rosario Ibarra, founder of the

Committee for the Defence of those Imprisoned, Persecuted, Disappeared and Exiled

for Political Reasons (known as the Eureka Committee).

"Don’t

ever think that they are dead. Look for them as hard as you can, fight as hard

as you can. I have been fighting since 1975, I’m already old now," said

Ibarra, who visited the mothers at the camp they set up on Thursday May 10 at

the Ángel de la Independencia monument, a focal point for protest in Mexico

City.

Most of the

women are indirect victims of the war on drugs and crime launched by President

Calderón at the start of his term in December 2006. Since then, the groups that

organised the caravan have documented more than 800 disappearances.

There are

no official figures. The only indication of the magnitude of the phenomenon has

come from the National Human Rights Commission - an independent government body

- in April 2010, when it reported that it had received 5,397 reports of people

who have gone missing since the start of the Calderón administration, and that

nearly 9,000 dead bodies had never been identified.

Nitzia and

Mita, 16-year-old twins, are looking for their mother, Nitzia Paola Alvarado,

who was detained by members of the military on Dec. 29, 2009 along with their

uncle José Ángel and their cousin Rocío in the town of

Due to

harassment and threats, 37 members of the family were forced to flee the state.

The

caravan, which returned north over the weekend, received a letter from victims’

relatives who formed the group LUPA (the Spanish acronym for Struggle for Love,

Truth and Justice), in Nuevo León, one of the states hit hardest by the

spiralling violence, where 49 decapitated and dismembered bodies were found

along a highway on Sunday.

"There

are no words to describe the pain that mothers feel when a son or daughter

disappears…but if we had to try to describe it, if we had to find words, we

would tell you it is a terrible ordeal, a via crucis that never ends, unending

agony," says the letter.

"Our

pain and our struggle for our missing sons and daughters are heightened when we

see that part of society is indifferent, when we see a government that also

contains corrupt authorities who are in league with criminal elements,"

LUPA adds.

These women

who have lost sons and daughters and who don’t know what to tell their

grandchildren when they ask what happened to their father or mother have

decided to channel their pain into the struggle for justice.

Julia

Ramírez has 12 children. Alejandro, the oldest, decided to migrate to the

"My

children told me there would be a mother’s day festival. It was really hard for

me to leave them, but I have to continue the search; they’re at home, but their

brother isn’t," she said.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

WHEN THE MISSING DON'T RETURN

- October 17, 2013

- Some call it ‘frozen loss,’ a

point in time that families and relatives find almost impossible to extricate

themselves out of, even years after their loved ones have disappeared.

“The

families of the missing get into a [state of] tunnel vision,” says Bhava

Poudyal, mental health delegate for the International Committee of the Red

Cross (ICRC) in Azerbaijan. He is talking about the thousands of families still

searching for their loved ones who have gone missing in his native Nepal, or in

Sri Lanka, Azerbaijan and dozens of other countries.

It’s a

situation that does not let go of its captives easily. “Their lives are

dominated by the missing, there is no release,” he tells IPS. “They live with

the ambivalence of hope and despair day in and day out.”

“Everyone seeks answers all the

time, the state of ambiguous loss is torture."

It’s a

condition Santhikumar, a bicycle repairman in his forties in Oddusudan village

of the Mullaitivu district in Sri Lanka’s Northern Province, is all too

familiar with. It has been four years since his brother-in-law went missing

during the final stages of the Sri Lankan military’s war against the rebel

Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in April 2009.

Santhikumar

has been helping his sister and her two daughters make ends meet even as he

joins them in the search for the breadwinner of their family. He has visited

every official detention centre in the north and nearby areas, but with no luck

so far.

“People come

and tell us that they saw him on this location on this day. So we go looking

for him there,” he says. “But we have not found anything concrete yet.”

The family

has got used to the never-ending search, he adds. “There are good days and bad

days. Mostly we are okay, but there are days when my sister just stares

aimlessly for hours, or when her daughters break down crying. Birthdays are the

hardest, the girls have so many memories of appa (father).”

Some 2,300

km and a whole country away, Rena Mecha shares the same feeling of despair in

the Jalthal village of Jhapa district in eastern Nepal. The 36-year-old mother

of a boy and girl, 16 and 14 respectively, has been searching for her husband

who went missing during the pro-democracy movement in the country in 2006. “I

lost everything when he went missing,” she tells IPS. “Nothing can bring that

life back.”

The current

ICRC documentation shows that around 1,400 people have been missing in Nepal

since the 2006 peace agreement. In the country’s rural areas, the wives of the

missing men desist from calling themselves widows, as that would entail a whole

new set of complications, like having to dress in white and being considered a

‘bad presence’ by others.

In southern

Sri Lanka too, the immediate community has ostracised women who have accepted

that their missing husbands are dead, accusing them of betraying their

husbands, says Ananda Galappatti, a medical anthropologist who works with the

families of the missing in the country.

In

Azerbaijan, says Poudyal, many families continue to cook meals and set a plate

for a missing person even long after their disappearance. Close to 4,600 people

went missing during the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between the republics of

Azerbaijan and Armenia after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

“It is the

constant state of waiting which makes closure very difficult, if not

impossible,” Zurab Burduli, the ICRC protection delegate in Sri Lanka, tells

IPS.

Galappatti

says the families are assailed by an identity crisis that can be exacerbated by

the social environment. “Am I a married woman or a widow? Am I a child without

a father? Am I a parent whose daughter is dead? Planning for the future

becomes extremely difficult in this situation,” he tells IPS.

In Sri

Lanka, the number of missing persons is a contentious issue. A presidential

task force set up to investigate the southern insurrection by the Janata

Vimukhti Peramuna (JVP) in the late 1980s recorded at least 30,000 cases of

missing people in 1995. The ICRC has a current caseload of 16,090 missing

persons in Sri Lanka dating back from 1990.

According to

Burduli, the first step in assisting these families is to recognise their

complex situation and devise assistance plans targeting them.

“The ICRC’s

experience around the world shows that because of the complexity of the needs

and their multi-disciplinary nature, coordinative national mechanisms are best

suited to address those needs in a comprehensive and consistent manner,” he

says.

In Nepal,

the families of the missing admit that once the national tracing programme

began following the 2006 peace agreement, their situation improved slightly.

“I was the

only one in my village with someone missing, I felt so alone,” says Mecha. “Now

at least there are people who understand my situation.”

Grassroots

groups provide families psychosocial support here, something that is yet to

take root in Sri Lanka.

“It is

imperative that any public process also includes the psychosocial accompaniment

of families – with sensitive and skilled practitioners on hand to support

families as they prepare for or go through these processes,” says Galapatti.

At the same

time, officials with the Nepali Red Cross who work as tracing officers warn

that the process of dealing with the families is slow and time-consuming.

“Everyone

seeks answers all the time, the state of ambiguous loss is torture,” says

Shubadhra Devkota from the Nepali Red Cross.

____________________________________________________

WUNRN

http://www.ammsa.com/content/missing-and-murdered-aboriginal-women

CANADA - CALL FOR INVESTIGATION INTO MISSION NATIVE/ABORIGINAL WOMEN

& GIRLS

Women’s Marches Demand Justice for the Disappeared Aboriginal Women.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

WUNRN

The

Russia-Chechnya - Women with Photos to Mourn

"Disappeared" Relatives

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

WUNRN

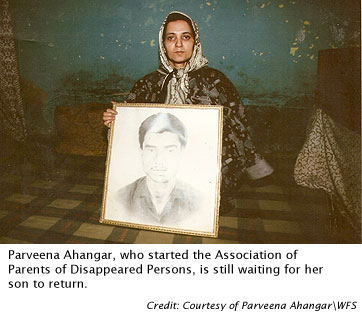

INDIA-KASHMIR - MOTHERS OF THE DISAPPEARED SEARCH & SUFFER

Ahangar

hasn't known peace for years.

Ahangar

hasn't known peace for years.

"I can't describe how each day passes. I keep taking medicines

every single day to control my tension. At night, I'm awake. I just can't

sleep," Ahangar says.

She's felt this way, she says, ever since the day 21 years ago when she

lost her son.

"My teenaged son, Javed, was picked by the security agencies in

1990," she says.

"Security men came to our Batmaloo home to pick him up, saying they

were taking him for interrogation. We pleaded with them, saying he couldn't

have done anything wrong, that he had just passed his matriculation. But they

didn't listen and took him to the interrogation center at Pari Mahal. We never saw

him again."

Ahangar's husband fell ill because of the trauma, and gave up working.

He remains in poor health today.

Ahangar lives in the India-administered state of

She has scoured the

Many other women in the

"I can't describe how

each day passes. I keep taking medicines every single day to control my

tension. At night, I'm awake. I just can't sleep," Ahangar says.

She's felt this way, she

says, ever since the day 21 years ago when she lost her son.

"My teenaged son, Javed,

was picked by the security agencies in 1990," she says.

"Security men came to

our Batmaloo home to pick him up, saying they were taking him for

interrogation. We pleaded with them, saying he couldn't have done anything

wrong, that he had just passed his matriculation. But they didn't listen and

took him to the interrogation center at Pari Mahal. We never saw him

again."

Ahangar's husband fell ill

because of the trauma, and gave up working. He remains in poor health today.

They say they've sold land, homes, jewelry; exhausted every asset in the

search for their children.

Never Giving Up'

Ahangar provides leadership for many of them through the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP), which she co-founded in 1996.

"I have decided never to give up this nonviolent protest of ours

until my last breath," she says.

On its website, the APDP describes the problem of "enforced

disappearances" as starting in 1989, when a group of young men took up

arms against the Indian state in support of the longstanding popular movement

for self-determination in Kashmir, which began in 1947 after the creation of

"In the name of national security and state interest the massive

Indian security apparatus in the state has been operating in a climate of

impunity shielded by emergency legal provisions like the Disturbed Area Act and

Armed Forces Special Powers Act, which grant immunity against being held

accountable," says the site.

Ahangar began her organization after a small group of parents, all of

whom had undergone the trauma of having their children taken away from them and

then found missing, came together.

Support has been building.

This year, she was nominated for the Frontline Human Rights Defenders

Award 2011. Civil libertarians in

The once-tiny group now has offices in almost all districts of the

She is currently trying to prosecute security forces for the

disappearance of her son through a lawsuit in the High Court with a prominent

lawyer, Zafar Shah, volunteering to represent her.

"I could not have afforded a lawyer," says Ahangar.

"Fortunately for me, Zafar sahib is not charging me. In fact, there are

many lawyers in the state who have taken up the cases of missing children

without charging a paisa (a cent) because they realize that we are not in a

position to pay and the issue is a crucial one that needs to be redressed. It

is an outrage that while we continue to suffer, those responsible for the crime

have not been booked and are, in fact, roaming about freely."

The Same Question

The APDP members have met numerous prominent political leaders of the

Ahangar says she asks all of them the same question: How would they feel

if their own young sons were picked up and never seen again?

When Radha Kumar, the government appointed interlocutor, visited the

APDP office in Srinagar, Ahangar says she asked her to ask all the high-ranking

female politicians in New Delhi how they would react if their innocent children

were to be picked up and tortured by security agencies.

The APDP has long argued that over 8,000 men have gone missing in the

The state government has now even offered to conduct DNA profiling on

these bodies in order to identify them.

Ahangar, however, refuses to be diverted by the issue of unmarked

graves.

"I know this whole issue of unmarked graves is a very serious

one," she says, "but don't link the missing with that issue because

then attention will get diverted. This is what the government authorities want;

they don't want attention to be focused on our missing children."

She points out how, over the years, misleading facts and figures have

been put out for public consumption, but the truth has always remained hidden.

With no closure in sight, Ahangar says there is no APDP member who will

ever give up.

"I just pray to Allah to give me the 'himmat' (courage) to carry on," she says.

__________________________________________________