WUNRN

Israel - Rites of Marriage

No

civil marriage - Religious rules prevail.

By Ariel David

|

Jun. 3, 2014

An

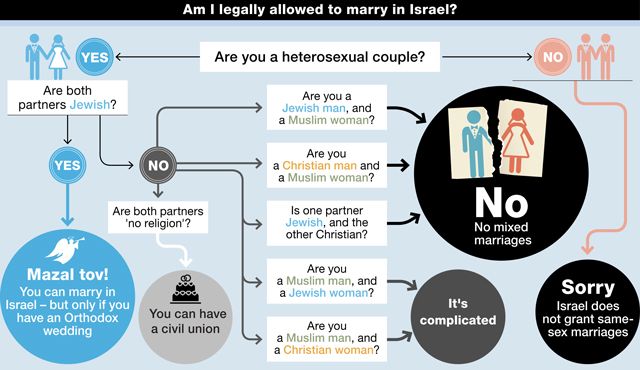

easy, simplified guide to intermarriage in

On the website of Hiddush, a nonprofit

organization that promotes religious freedom and equality in

Marriage in the Jewish state is a complex

matter, and is almost entirely under the purview of religious authorities.

There is no civil marriage. Jews can only be

married in a religious ceremony, by an Orthodox rabbi under the authority of

the Chief Rabbinate, the top religious authority for Jews in

Other religious authorities recognized by

This religious monopoly, which has no equal

among other Western democracies, puts people whose religious status is

registered as “other” in a particularly precarious position. This mainly

affects immigrants from the former

In 2010, in an attempt to solve this issue,

the Knesset passed a law that recognizes civil unions, but only if both

partners are registered as not belonging to any religion. Civil rights groups

criticized the law for being too restrictive and stigmatizing because, in

practice, it forces these immigrants to marry only amongst themselves.

According to Hiddush, which filed a freedom

of information request with the Interior Ministry, only an average of 18

couples a year have taken advantage of the new law.

Some of these immigrants and other non-Jews

residing in Israel attempt to solve the problem by officially converting to

Judaism, but only Orthodox conversions are considered valid and the process is

lengthy and complex, and requires applicants, most of whom are secular, to

pledge a high degree of observance of Jewish rules.

Since the 1960s, following a landmark Supreme

Court ruling, many interfaith couples have been able to get around the law by

marrying abroad – Cyprus is the closest and one of the most popular

destinations – and then having the union recognized by Israel’s Interior

Ministry.

This process too can be tedious and

intrusive, particularly when one of the couple’s members is not Israeli, which

leads ministry officials to demand proof that the marriage was genuine and not

done for the purpose of obtaining citizenship. Couples are subjected to

detailed questioning and asked to produce pictures, letters and other evidence

of the nature of their relationship.

Rabbi Uri Regev, the president and CEO of

Hiddush, noted that even Israeli couple in which both partners are

unquestionably Jewish according to Orthodox religious law increasingly reject

marriage in favor of cohabitation, because of the Orthodox establishment’s

power over the institution. Some secular Israelis object in particular to what

they see as the non-egalitarian nature of the Orthodox ceremony, he said.

They also do not want to fall under the

jurisdiction of rabbinical courts in the event they decide to divorce. Under

Jewish law, in order for a couple to divorce the husband must grant a get, or a

divorce decree, to the wife. This stipulation can transform a woman into an

“agunah,” a wife who cannot remarry and is “chained” to her husband until he agrees

to grant the divorce.

Same-sex couples are also excluded from

marrying. Several proposals for a law introducing civil marriage in