|

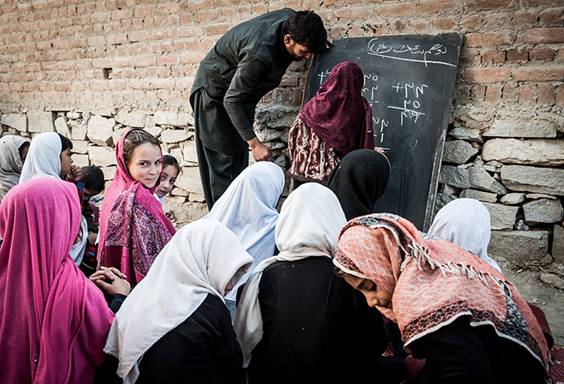

An Norweigan

Refugee Council -supported school in Nangarhar province, Afghanistan,

welcomes IDP

children into its classes.- NRC/Christian Jepsen, November 2013

WOMEN

& CHILDREN INTERNALLY DISPLACED IN AFGHANISTAN

Internally

displaced women and girls are particularly vulnerable as their low economic

status, social isolation and lack of traditional social protection

mechanisms place them at higher risk of abuses such as prostitution and

early and forced marriages. Widowed women, who represent an estimated 19.3

per cent of the IDP population, are disproportionately at risk due to the

removal of their traditional social protection mechanism, a male family

member, and often poverty prevents them from making inheritance claims (Samuel

Hall, January 2014, pp.82-83, NRC, March 2014, p.59).

This is related to economic hardship brought on by lack of income and

hardships exacerbated through displacement. While domestic violence is a

national concern, women reported that violence occurred more often during

displacement, because their husbands were “more stressed” (FMR, May 2014, p. 34;

Samuel

Hall, January 2014, pp.82- 83; NRC, 2008).

Discrimination

against displaced women is often exacerbated by detrimental social norms

and practices within Afghan conservative society. In particular, the legal

status of women and the decision-making power remain linked to that of a

male relative, and they are unlikely to own land, inherit or have security

of tenure should their husband or another male relative from which they

depend die, divorce or disappear (NRC, 2014).

In eastern Afghanistan, maternal and child health, protection against

sexual gender based violence and child abuse, are almost completely absent

from sector responses and there are hardly any prevention and response

mechanisms. Access to education is lowest among conflict-induced IDPs, with

the strongest reluctance towards girls’ education (Samuel Hall/CFA 2013,

p.38 and p.85).

Children

are often forced into child labour to support their families, preventing

them from attending school and putting them at risk of child recruitment (OCHA,

November 2013 p. 15) The Taliban have used children to carry-out suicide

attacks. Interviews with children who survived due to mechanical failures

or who were imprisoned after a failed attack, stated they did not even know

what a suicide attack was (Xinhua,

August 2013, HRW,

August 2011). Afghanistan adopted a Juvenile Code-Procedural Law for

Dealing with Children in Conflict with the Law in 2005 and in 2009 a Law of

Juvenile Rehabilitation Centers which incorporate basic principles of

juvenile justice set out in the Convention on the Rights of the Child

(CRC). However, children in detention continue to face rights violations

including sometimes being detained with adults, not adequately provided

with food, care, protection, education and vocational training and abuse

and torture (UN

CRC, February 2011, p.17). Children are not also provided with legal

aid, including before courts, and often statements are forcibly extracted (UN

CRC, February 2011, p.17).

IDP

children who go to unfamiliar places looking for firewood during the winter

are at a higher risk of injury or fatality as they may readily mistake

‘butterfly’ mines for toys. UNAMA documented 511 child casualties in 2013

due to IEDs, a 28 per cent increase from 2012 while nearly 55 per cent or

964 child casualties resulted from actions of NSAGs (UNAMA,

February 2014, p.59).

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Afghanistan

is in a political, security and economic transition. The International

Security Assistance Forces (ISAF) will hand over full responsibility for

security to the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) at the end of 2014,

a new president and provincial authorities will assume office and the

economy will need to adjust to a loss of international military spending.

During this period of transition, Afghanistan’s political, security and

economic stability are uncertain. As such, humanitarian access has become a

key concern, particularly for internally displaced people (IDPs) in rural

or remote areas where development and humanitarian actors have limited

access due to insecurity and on-going conflict. Shrinking

humanitarian space does not translate into shrinking needs and, if

anything, multiplies them. Internal displacement continues to rise against

a backdrop of continuing armed conflict, high rate of civilian casualties,

increased abuses by non-state armed groups (NSAGs) and pervasive

conflict-related violence.

|