WUNRN

RUSSIA - 5 SENTENCED FOR MURDER OF

JOURNALIST ANNA POLITKOVSKAYA

VIENNA, 10

June 2014 – OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media Dunja Mijatović

today welcomed the sentences handed down to five individuals for the murder of

journalist Anna Politkovskaya in 2006, but called for the investigation to

continue to bring the masterminds to justice. “The Politkovskaya case is still

not closed until those who ordered this horrific murder are identified and

convicted. Anna’s family, friends and colleagues around the world deserve

justice”, Mijatović said. On June 9 the Moscow City Court found five

individuals, including three defendants acquitted in the previous trial, guilty

of planning, participating, and carrying out the murder of Politkovskaya. They

received lengthy prison sentences. The court ruling was based on the jury trial

verdict which on 22 May found all five suspects guilty. The court also

confirmed that Politkovskaya was killed for her critical reporting. However,

the investigation was unable to name the masterminds of the crime.

Journalist

Anna Politkovskaya was shot and killed in Moscow on 7 October 2006, in her

residential building. Politkovskaya was known for her critical views and

reports, including on the Chechnya War.

____________________________________________________________________

----- Original Message -----

From: WUNRN

ListServe

To: WUNRN ListServe

Sent: Saturday, August 27, 2011 10:01 AM

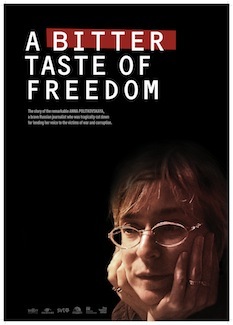

Subject: Russia - Anna Politkovskaya Slain Rights Journalist - Movie

WUNRN

Website Link Includes Film Segment.

ANNA POLITKOVSKAYA,

SLAIN RUSSIAN RIGHTS JOURNALIST - NEW MOVIE

by

Alexandra Marie Daniels

Someone tried to silence Anna Politkovskaya. An investigative journalist with a

bleeding heart, she was assassinated on October 7, 2006 at age 48 in her

apartment building in

As expressed in the

opening scenes of the new film A

Bitter Taste of Freedom, Anna was

Though other films were made about Anna Politkovskaya after her

death, A Bitter Taste of

Freedom is unique. It is a ‘visual portrait,’ a window into Anna’s

life, created by one of her most intimate friends, Russian filmmaker Marina

Goldovskaya.

As part of the

International Documentary Association's 15th Annual DocuWeeks™ Theatrical

Documentary Showcase I had the opportunity to sit down with Marina

Goldovskaya and discuss their friendship and her new film.

Anna Politkovskaya and

her husband Sasha were former students of Goldovskaya at

As a documentary

filmmaker Goldovskaya's goal is to preserve history. As a woman experiencing a

transformative period in Russian history she did not hesitate to film every

possible moment she could.

“With Gorbachev,”

Goldovskaya explains, “It was euphoric…Freedom was something we didn’t know,

and we still know very little about…We thought, this is the beginning of a

completely new era…My goal was to make a film to show the changes, where they

are going, and I started shooting.”

But Goldovskaya feels

that “in order to make a film about a political issue, it has to be very

well-grounded in the reality, in life.”

At age 48 Anna

Politkovskaya was assassinated in

During the making of A

Taste of Freedom, Sasha was often away on assignments and

Goldovskaya spent many hours filming conversations with Anna at the Politkovsky

home while she raised her two children. A

Bitter Taste of Freedom spans their 20-year friendship.

Taking time with her

words as she takes time with her coffee, Ms. Goldovskaya explains “there are

people with very thick skin…There are people with thin skin and there are

people without skin…I have a thin skin. I really take things very close to

heart…Anna was a person with no skin at all.” Deeply affected by what she saw,

Anna’s emotions were raw and it was for this reason that Anna did her work and

genuinely did it well.

Despite her fear Anna

traveled regularly back of forth between

She explains how Anna

disguised herself as a Chechen woman by wearing long skirts; how despite poor

vision, Anna would remove her glasses because Chechen women did not wear

glasses; and how she put a scarf on her head to hide.

“She would go there and

talk to people in villages, in private homes, and of course she never knew what

was going to happen. A couple of times she was arrested by the Federal Russian

Guard. She continued to do it, risking her life, it was a part of her.”

Anna became a human

rights activist defending the innocent civilians whose lives were destroyed. “Shocked

and traumatized,” she felt she had no choice but to report on the atrocities of

war. The work was dangerous but Anna never looked back.

The chief editor of Novaya Gazeta, the

newspaper where Anna worked, said many times “stop going, I am afraid for you;”

but Anna maintained an attitude of “if not me, then who?”

Goldovskaya never

accompanied Anna on her trips to

Investigative journalist for

As a journalist Anna was not able to ignore her responsibility to

society. Russian authorities did not like her reporting from

Dmitry Bykov, a writer

interviewed in the film, believed that “her point of view was deeply affected

by what she saw,” and commented that “by virtue of her passionate female

concern for

Striking me as absurd, I

asked Goldovskaya about Bykov’s comment. She explains “it is a part of Russian

patriarchal society, the remnants…an inescapable part of Russian mentality.”

She tells me “Anna Politkovskaya made many of her colleagues uncomfortable. Her

feminine perspective even disgusted some.”

]

Despite the conflicting

feelings towards her, Anna followed her raw emotions. She became a voice for

the Chechen people - establishing relationships and becoming someone they could

trust. In 2002, Politkovskaya was asked to be a negotiator during the Nordost

theater siege by armed Chechen rebels. Very sadly, Anna was not able to help.

Thirty-nine rebels along with at least 129 hostages were killed when Russian

forces pumped toxic gas into the theater to end the raid.

Former Soviet leader

Mikhail Gorbachev describes Anna in the film as “a remarkable

journalist…because she was a remarkable person.” He explains that she was

strong and ethical and went on to say that “life is always hard for such people…In

her heart and in her mind she wanted to see the country improved, for the

people to feel…confident. And free.”

Anna’s conscience

propelled Goldovskaya to make A

Bitter Taste of Freedom; and through it, she continues to live.

After seeing the documentary and speaking with Marina Goldovskaya I believe we

should all ask, “if not me, then who?”

About the Author:

Alexandra Marie

Daniels

is a writer, dancer, and filmmaker. She has made three films with the director

Bernard Rose, including The

Kreutzer Sonata (2008) and Mr.

Nice (2010) and has worked with the director Martyn Atkins as a

script supervisor on concerts such as Eric

Clapton and Steve Winwood: Live from Madison Square Garden and The Crossroads Guitar Festival 2010.

Alexandra is The WIP's Arts, Culture, and Media Editor.

_____________________________________________________________________

----- Original Message -----

From: WUNRN

To: WUNRN ListServe

Sent: Wednesday, July 23, 2008 10:22 AM

Subject: Anna Politkovskaya - Slain Russian Journalist Rights

Defender - Movie: "Letter to Anna"

WUNRN

Letter

to Anna: Movie

The Story of

Slain Russian Journalist Anna Politkovskaya's Death

Anna

Politkovskaya

Анна

Степановна

Политковская

|

Born |

|

|

Died |

|

|

Occupation |

|

Letter

to Anna: Movie - Summary

Anna

Politkovskaya was a Russian reporter who regularly wrote for Novaya Gazyeta,

one of the country's few independent journals. In a nation where political

corruption is widespread and exposing the misdeeds of the nation's leaders often

has dangerous consequences, Politkovskaya was a fearless voice whose stories

demanded responsibility from Vladimir Putin and his colleagues while decrying

Russia's actions in Chechnya, which she labeled as genocide. While

Politkovskaya writings earned her respect and made her one of the nation's best

known journalists, they also angered many powerful people; she nearly died

after she was poisoned in 2004 while covering the Beslan school hostage case,

and in October 2006 she was shot and killed by an unknown gunman while riding

an elevator in her apartment building; many of her friends and family believe

she was assassinated by government agents. Filmmaker Eric Bergkraut struck up a

friendship with Politkovskaya while making his documentary Coca: The Dove From

Chechnya, and Ein Artikel zu viel: Der Mord an Anna Politkowskaja (aka Letter

To Anna: The Story Of Journalist Politkovskaya's Death features archival

interviews with the late reporter, as well as contributions from colleagues and

loved ones who discuss her work and offer their views on her suspicious

passing. Letter To Anna received its North American premiere at the 2008

Toronto Hot Docs Film Festival. Mark Deming, All Movie Guide

______________________________________________________________________

WUNRN

TRIBUTE TO SLAIN RUSSIAN WOMAN

JOURNALIST

ANNA POLITKOVSKAYA

Politkovskaya:

A Life for Justice

By Swanee

Hunt

October 10, 2006

Everyone needs a hero. Anna Politkovskaya was mine. And others’. In addition to the 2005 Civil Courage Prize, she received the Courage in Journalism Award from the International Women's Media Foundation in 2002, as well as prizes from the Overseas Press Club and Amnesty International. In 2004, she was a joint winner of the Olof Palme Prize for her human rights work.

I met Anna in November, 2000, at Women Waging Peace, a network of about 450 leaders within the Initiative for Inclusive Security, which advocates for the full inclusion of women in peace processes around the world. That initiative was incubated at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. We try to protect and support women peace experts in part by bringing them to the attention of policy makers at the State Department, World Bank, White House, and other halls of power.

This past Saturday Anna was executed: shot point blank in the head with a revolver outside her apartment. The gun was placed by her side, indicating a contract-killing. She was 48.

Born in 1958, Anna graduated from

She told me once that because she was female, she was considered less

threatening and could get behind the lines, where she reported on abuses the

army was perpetrating against Muslim communities under cover of fighting

terrorism. She described how, to avoid a military checkpoint, she’d made her

way down to a river, then trekked through deep snow all night. Another

time, she posed as a farm wife sitting on a pile of hay in a wagon; she smiled

that without her wire-rims she couldn’t see a thing. Another time she was

apprehended by Russian forces but freed as night fell by a sympathetic major.

In February 2000, the FSB (former KGB) confined her in a pit in

Despite those dangers, like many of the women we have sponsored, Anna Politkovskaya kept working to expose the injustices around her. Fearless, but not naïve, she knew her life was on the line as she described the moral decay of 100,000 security forces, whose abuses only spawn more terrorism. Still, she continued to document zachistka ("mop-up"), where young men, or any others considered suspicious, are rounded up from their homes, sometimes tortured, and often executed.

Because of her standing with the Chechens, Politkovskaya acted as a mediator

during the Dubrovka Theater siege in

I last saw Anna in December. She and a small group were discussing the role of women in the security sector, as protectors of human rights, journalists, politicians, and leaders of civil society. They called for women’s solidarity internationally to ensure peace and stability. Anna spoke about freedom of speech and how crucial it is for NGOs to challenge the government. Her words then bear the weight of her sacrifice now.

That day I took two pictures of Anna: the first, somber; the second, her head back, laughing. I think of those two images of her as we mourn her murder and celebrate her life. She understood that with freedom comes responsibility to work for those denied such freedom. As we grieve her death, forty years too soon, we must redouble our efforts and carry forward her legacy.

Swanee Hunt, former