WUNRN

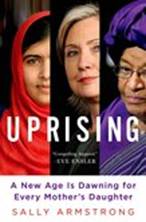

From Africa to Asia to the Americas, women are the key to progress on ending poverty, violence, and conflict. Award-winning humanitarian and journalist Sally Armstrong shows us why empowering women and girls is the way forward, and she introduces us to the leading females who are making change happen, from Nobel Prize winners to little girls suing from justice. Uprising tells dramatic and empowering stories of change-makers and examines the stunning courage, tenacity and wit they are using to alter the status quo. From mud-brick houses in Afghanistan to the forests of Congo, where women still hide from their attackers, to a shelter in northern Kenya, where 160 girls between 3 and 17 have won an historic court case against a government who did not protect them from rape, to Pakistan, where Malala Yousafzai is fighting for the rights of women everywhere, Uprising is about the final frontier for women: having control over your own body, whether in zones of conflict, in rural villages, on university campuses or in your own kitchen. In this landmark book that ties together feminism and our global economy, Sally Armstrong brings us the voices of the women all over the world whose bravery and strength is changing the world as we know it.

About the Author, Sally

Armstrong - Human rights activist and journalist SALLY ARMSTRONG has covered

stories about women and girls in zones of conflict all over the world. Her eye

witness reports have earned her awards including the Gold Award from the

National Magazine Awards Foundation. She received the Amnesty International

Media Award in 2000, 2002 and 2011, and she was a member of the International

Women’s Commission, a UN body whose mandate is assisting with the path to peace

in the Middle East.

CHAPTER

1 - THE SHAME ISN'T OURS, IT'S YOURS

The first corner turning was realizing we weren’t crazy. The system was

crazy.GLORIA STEINEM

Rape is hardly the first thing I would want to mention after delivering the

uplifting news that women have reached a tipping point in the fight for

emancipation. But as much as major corporations now want women on their boards,

and the women of the Arab Spring have flexed their might in overthrowing

dictators, and the women of Afghanistan and elsewhere are prepared to go to the

barricades to alter their status, sexual violence still stalks them. It doesn’t

stop women from reforming justice systems, opening schools, and establishing

health care. It doesn’t eliminate them from leadership roles or prevent them

from acting as mentors and role models. But rape continues to be the ugly

foundation of women’s story of change. Burying the terrible truth is as

ineffective as wishing it hadn’t happened. Naming the horror of sexual violence

is a crucial part of the change cycle.

Rape as punishment or as a means of control still lurks in the lives of women.

Marital rape is an old story. Date rape is relatively new. In many households,

husbands still claim that they own their wives and have the right to sex on

demand. Defenseless children are sexually abused by fathers, uncles, and

brothers; in some countries, men think that having sex with a virgin girl child

will cure HIV/AIDS. The impunity of men when it comes to rape constitutes a

centuries-old record of disgrace. For women, sexual violence has been a life

sentence.

I’ve spoken to women in Africa and Europe, in Asia and North America about the

role of rape in their lives. Some of the stories they told me made me gasp in

near disbelief at the extent of the horror inflicted on them. Others made me

cheer for the awe-inspiring courage they showed in demanding justice. They all

described perpetrators who banked on the silence of society and the shame of

the victims to protect them from consequences. But they also spoke of the

fearlessness and tenacity it takes to end this scourge.

Some people think you shouldn’t talk about rape. If it happens to you, be

quiet, don’t tell, because the stigma could prevent you from getting a job,

making new friends, finding a partner. People say, “Put it behind you. There is

no good in rehashing the past.” Others still dare to say, “She asked for it.

She was dressed like a whore.” Or worse, “She needed to be taught a lesson.”

And too many people refuse to accept the statistics. They don’t want to believe

that one human being could be so brutal to another human being, so they dismiss

the topic as not fit for polite conversation. People who don’t intervene when

something is wrong give tacit permission for injustice to continue, proving

that there’s no such thing as an innocent bystander.

Rape has always been a silent crime. The victim doesn’t want to admit what

happened to her lest she be dismissed or rejected. The rest of the world would

prefer to either believe rape doesn’t happen or stick to the foolish idea that

silence is the best response.

Today the taboo around talking about sexual violence has been breached.

Women from Bosnia, Rwanda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo have blown

the whistle about rape camps and mass rapes and even re-rape, a word coined by

women in Congo to describe the condition of being raped by members of one

militia and raped again when another swaggers into their village. Instead of

being hushed up, cases such as that of Mukhtar Mai, the Pakistani girl who was

gang-raped by village men who wanted to punish her for walking with a boy from

an upper caste, have made headlines around the world. And the raping of an

unconscious girl in Steubenville, Ohio, in 2012 got everyone’s attention,

mostly because some of the media reported that the “poor boys who raped her

were going to jail and their lives were over.” An outraged public responded

with a conversation that went viral: “If you’re so worried about your high

marks and your great ‘rep’ and your football scholarship, don’t go around

raping unconscious girls and posting the photos on YouTube.”

The causes and consequences of rape are at last being debated at the United

Nations. The International Criminal Court in The Hague declared rape a war

crime in 1998. The UN Security Council decided that rape was a strategy of war

and therefore a security issue in 2007. The announcement was welcome news to

the activists, but most people asked what the Security Council could or would

actually do with their newly forged resolution, which called for the immediate

and complete cessation by all parties to armed conflict of all acts of sexual

violence against civilians. The resolution also called for states to provide

more protection for women and to eliminate the impunity of men. Getting

traction on a UN resolution is like hoping for rain in the middle of a drought.

Women are fed up with waiting for action. Eve Ensler, the award-winning

playwright, author of The Vagina Monologues, and founder of V-Day, the global

activism movement to end violence against women and girls, had an idea. What if

1 billion women around the world stood up on the same day and sang the same

song and danced the same dance? What if together they claimed their own space,

raised their own voices, took back the night? Would that send a message that 50

percent of the population has had it with violence against women? The naysayers

said it could never be done. But the naysayers hadn’t asked the world’s women.

On February 14, 2013, 1 billion women from India and the Philippines to the

United States, the United Kingdom, and Germany danced, sang, and reclaimed

their own bodies.

On February 14, 2014, they did it again. Thousands of pairs of feet stomping, hands clapping; little kids and grannies, businesswomen and teenagers flooded into public squares in 207 countries. They danced, raised their arms skyward, and sang in a victory chant that was heard all over the world.

I dance ’cause I love,

Dance ’cause I dream,

Dance ’cause I’ve had enough,

Dance to stop the screams

Dance to break the rules

Dance to stop the pain

Dance to turn it upside down

It’s time to break the chain

They were taking part in One Billion Rising, which was the largest global action

in history to end violence against women. Like a rising tide, the decision to

stop the oppression, the abuse, the second-class citizenship of women was

already surging in Asia, in Africa, in North America and Europe. When Eve

Ensler did the math, she made a startling announcement: “One in three women on

the planet will be raped or beaten in her lifetime. One billion women violated

is an atrocity. One billion women dancing is a revolution.”

The idea came to her when she returned to the Democratic Republic of Congoto

Bukavu and the City of Joy she had built with the women who had suffered the

worst and likely most depraved abuse the world had ever known. It was a bald

and thin Eve Ensler who had just stumbled out of the fog and fear of uterine

cancer treatment who fell into the welcoming arms of the women she had worked

with in what had come to be known as the rape capital of the world. Eve linked

her own cancer to the cancer of cruelty that these women knew. In her new book,

In the Body of the World, she describes “the cancer from the stress of not

achieving, the cancer of buried trauma” and the epiphany she had that “cancer

was the alchemist, an agent of change”: “I am particularly grateful for the

women of Congo whose strength, beauty, and joy in the midst of horror insisted

I rise above my self-pity.”

It was there she imagined the dance. “It could transform suffering into action

and pain into power. We could call on all women to dance, to take back the

spaces, put their feet on the earth, reclaim their bodies.” The idea spread

like wildfire: urban and rural women, farmers and fishers, artists and teachers

all said they would dance.

Eve Ensler says, “Dancing is a genius form of protest. You can do it together

or alone, it gives you energy, makes you feel you own the street. Corporations

can’t control it.” She lists dozens of events that made up One Billion Rising:

a flash mob in the European Parliament, more than forty events in New York

City, participation by cell phone in Tehran, a human chain in Dhaka,

Bangladesh, and acid attack survivors in that country who rallied and danced.

Fifteen city blocks in Manila had to be closed to accommodate more than a

million women dancing. Two hundred women and men marched in front of the

parliament in Afghanistan. There was the first-ever flash dance in Mogadishu,

Somalia, and more than two hundred events in the United Kingdom. Hollywood

actors like Anne Hathaway rose up. So did the Dalai Lama and politicians and

CEOs. Eve says the participation was beyond her wildest dreams. She’s on a

mission to stop the violence that she calls “the methodology of oppression”

once and for all. Her goal was to find the right steps to end violence “so it’s

not perpetual Groundhog Day.”

One Billion Rising was the wind needed to blow on the coals so the fire would

ignite. And now she wants the international community to step up and keep

stoking the fire. “Our time has come,” she says. “This is the moment to trust

what you know, trust your instinct, move knowledge into wisdom. Now is the

moment to stop waiting for permission. Stand up for your truth.” She calls

women the people of the second wind and calls on all of us to keep rising.

One Billion Rising isn’t a single assault on violence against women. It’s part

of a collection of volleys against sexism and oppression that is gaining in

strength around the world today.

One of the most stunning examples comes from Kenya, where in 2011 there was a

watershed moment everyone had been waiting for. In the northern city of Meru,

160 girls between the ages of three and seventeen sued the government for

failing to protect them from being raped. Their legal action was crafted in

Canada, another country where women successfully sued the government for

failing to protect them. Everyone from high court judges and magistrates in

Kenya to researchers and law-school professors in Canada believed these girls

would win and that the victory would set a precedent that would alter the

status of women in Kenya and maybe all of Africa.

These are grand claims for redressing a crime as old as Methuselah, but the

researchers and lawyers working on the case insisted that the evidence was on

their side.

The suit was the brainchild of Fiona Sampson, winner of the 2014 New York Bar

Association Award for Distinction in International Law. She is the project

director of the Equality Effect, a nonprofit organization that uses

international human rights law to improve the lives of girls and women. It came

about by way of a touch of serendipity and a lot of tenacity. Sampson was doing

a master’s degree at Osgoode Hall Law School in Toronto in 2002 when she met

fellow students Winifred Kamau, a lecturer from the University of Nairobi Law

School, and Elizabeth Archampong, vice dean at the Faculty of Law at Kwame

Nkrumah University in Ghana, who had come to Canada to study international law.

Their mutual interest in equality rights drew the women together. A few years

later, when Seodi White, a lawyer from Malawi, was a visiting scholar at the

Center for Women’s Studies at the University of Toronto, the trio became a

foursome. When the African women wondered if the model used in Canada in the

early eighties to reform the law around sexual assaultin which legal activists

successfully lobbied to rewrite the law, educate the judiciary, and raise

awareness with the publiccould work in Africa, Sampson started thinking about

ways to tackle the entrenched violence against women in countries like Kenya,

Malawi, and Ghana.

Eight years after their initial meeting, the quartet gathered in Nairobi in

2010 with the pick of the human rights legal crop from Canada and Africa for

the historic launch of Three to Be Free, a program that targets three

countries, Kenya, Malawi, and Ghana, with three strategieslitigation, policy

reform, and legal educationover three years in order to alter the status of

women. Their intention was to tackle marital rape and make it a crime. But when

the lawyers returned home and started their research, another serendipitous

meeting took place. A woman named Mercy Chidi was in Toronto taking a course at

the Women’s Human Rights Education Institute at the University of Toronto. One

of the lawyers working on the marital rape case, Mary Eberts, was teaching the

course and heard Chidi’s story. She called Sampson and suggested she meet

Chidi, who was the director of a nongovernmental organization called The

Ripples International Brenda Boone Hope Centre (which is known locally in Meru

as Tumainithe Swahili word for “hope”). First a word about Brenda Boone, the

Washington-based executive whom the shelter is named for. She met Mercy in 2006

when Mercy was in Washington raising money to rescue kids with AIDS who’d been

abandoned. “I invited Mercy and her husband to come to my housethey arrived in

full African attire in my Capital Hill home that was full of antiques and

Victorian furniture.” Brenda asked how she could help, and when they asked her

for a computer, she provided one immediately, along with a check for $5,000. A

year later, Mercy was back in Washington to receive the International Peace

Award. Brenda invited the Chidis back to her home“I served them fried chicken

because it was Sunday and I’m Southern”and Mercy explained that they had made

a business plan and decided to open a shelter for girls who had been raped.

“That pierced my heart,” says Brenda. “I gave them another check, this time for

$25,000, and committed to financing everything to get the place going.” Brenda

knew the missing piece was the legal action required to stop the raping of

girls.

A few years later, when Mercy met Fiona Sampson and told her about the shelter

and about the girls who can’t go home because the men who raped them are still

at large, they both knew it was time to tackle the root of the problemthe

impunity of rapists and the failure of the justice system to convict them.

Sampson admits it was her own sense of urgency that made the concept take

flight. “I am the last thalidomide child to be born in Canada,” she explains,

referring to the anti-morning-sickness drug whose side effects in utero had

affected the development of her hands and arms. (The drug was banned in 1962.)

“There was a culture of impunity in the testing of drugs at that time,” she

explains, “so I’m consumed with the desire to seek justice in the face of

impunity.”

Kenya has laws on its books designed to protect girls from rape, or

“defilement.” The state is responsible for the police and the way police

enforce existing laws. Since the police in Kenya failed to arrest the

perpetrators and fail on an ongoing basis to provide the protection girls need,

the lawyers filed notice that the state is responsible for the breakdown in the

system. Sampson said at the time, “We will argue that the failure to protect

the girls from rape is actually a human rights violation, that it’s a violation

of the equality provisions of the Kenyan constitution. It’s the Kenyan state

that signed on to international, regional, and domestic equality provisions and

it’s therefore their obligation to protect the girls. Only the state can

provide the remedies we’re looking for, which is the safety and security of the

girls.”

Sampson and other human rights lawyers in Canada have done this successfully

for approximately twenty-five years since the introduction of Section 15, the

equality provision of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Their track record

includes considerable success with precedent-setting cases that establish the

state’s responsibility to protect the rights of Canadian women. One of them was

a case in Toronto in 1986 involving a woman raped by a man referred to as the

Balcony Rapist, who was targeting the women of one downtown neighborhood,

gaining access to their bedrooms by breaking in through second- and third-floor

balconies in the dark of night. The woman, who called herself Jane Doe, sued

the police, claiming it was their responsibility to warn the potential targets

of the Balcony Rapist and thereby protect them. The police tried to have her

case dismissed using the argument that if they had warned the potential

targets, it would have tipped off the rapist. But Jane Doe argued that the

Toronto police used her as bait to draw out the predator. Her courage and

dogged determination turned her case into a cause célčbre. In 1998, she won.

Mary Eberts, who is working on the Kenyan girls’ suit, explains the connection

between the two cases: “The police knew about this guy, they knew about his

method of operation, and they knew where in the city the women he liked to

target would be living, but they did not warn those women about the potential

danger they were in. Jane Doe was raped by this guy, as the police might have

predicted. She brought this case, which we are using as a precedent in the 160

girls’ litigation, to say there is a duty on the part of the police to enforce

the lawthat’s why the law is there. And if the police do not enforce the law,

if the government does not enforce the law, then they are guilty of violating a

person’s equality.”

Eberts knows that the stars need to be aligned for precedent-setting cases to

work. Her colleague Winnie Kamau says a case like this couldn’t have happened

even a few years ago. “I think the timing was actually quite perfect,

particularly in the Kenyan context,” Kamau says. “We have a new constitution

that was enacted in August 2010, and in the last half dozen years we have had

some very progressive laws passed in our country. Five years ago it would have

been difficult to bring everybody together, but the timing now I believe is

right. There’s also a lot more awareness among African women about their

rights, and they have the feeling, the sense that they need to change. We can

harness these energies.”

The new Kenyan constitution contains powerful provisions that provide for

increased equality for women and girls, provisions that have not yet been interpreted

by the country’s courts. This is precisely where the Canadian courts were

twenty-five years ago when the Charter of Rights and Freedoms was enacted. New

laws must be tested and interpreted in the courts. Reflecting on their own

experience with charter challenges, the Canadian lawyers see this case as an

opportunity to ensure that the courts interpret and apply constitutional

provisions in ways that guarantee the human rights of women and girls. The

process is time-consuming and expensive, but it’s the best way to establish

precedents that the courts can rely on for future cases. The Three to Be Free

activists plan to take similar action in Malawi and Ghana once this case is

won.

Historically, when you alter the status of one woman, you alter the status of

her family. When a girl is confident and knows what her rights are, she knows

what she can claim from the state and that the state owes her certain things by

virtue of the fact that she’s a citizen of that state. She can claim an

education, livelihood, and shelter. She can claim that she has the right not to

be marginalized. Once the state is held accountable for its obligation to

promote women’s human rights and to protect women and girls from violence, a

climate of intolerance for violence against women follows. There’s more

likelihood that people who talk casually about violating women and girls will

be censured by their friends and that women themselves will speak out, bring

charges, demand justice.

* * *

It’s a four-hour drive from Nairobi to Meru (population 1 million) and the

shelter where the Kenyan girls are staying. We drive through banana farms and

tea plantations, past dark umbrella-like acacia trees, inhaling the dry scent

of the savannah. Bleating goats and signs declaring JESUS SAVES dot the

landscape. Mango trees and roadsides drenched in pink, orange, and red

bougainvillea smack up against fluorescent green billboards advertising Safari,

the country’s cell phone provider. When we cross the equator on the way to

Meru, the heat intensifies but the traffic remains the sameheavy and fast, a

series of near misses for both vehicles and pedestrians.

The rutted red dirt road into the Ripples International shelter is shaded by a

canopy of lush trees that offer refuge from the heat of the equatorial sun.

Hedges of purple azalea and yellow hibiscus camouflage the fence that keeps

intruders away from this bucolic place that is a refuge for the 160 girls who

are poised to cut off the head of the snake that is sexual assault.

I’d been briefed in Nairobi about what to expect when I met the girls whose

cases have been selected for the lawsuit. The first one I’m introduced to is

Emily. The size of the child takes my breath away. Emily is barely four and a

half feet tall, her tiny shoulders scarcely twelve inches across. But when she

sits down to tell her story, her husky eleven-year-old voice is charged with

determination. “My grandfather asked me to fetch the torch,” she explains. But

when she brought it to him, it wasn’t a flashlight he wanted. “He took me by

force and warned me not to scream or he would cut me up.” Along with thousands

of men in Kenya and indeed throughout sub-Saharan Africa, Emily’s grandfather

believes that having sex with a girl child will cure HIV/AIDS, a belief that

led him to rape his own granddaughter to presumably heal himself. What’s worse,

men believe that the younger the child is, the stronger the cure will be. Now

she is taking the old man to the high court in Nairobi. Even Emily knows the

case is likely to be history making. This little kid, along with the other 159

plaintiffs, knows that she may be the one who strengthens the status of women

and girls not only in Kenya but in all of Africa.

“These men will learn they cannot do this to small girls,” says Emily, who,

like the other girls I met, balances the victim label with the newfound

empowerment that has come to her from the decision to sue.

Charity is also eleven and her sister Susan only six. Their mother is dead.

Their father raped themfirst Charity, then Susanafter they came home from

school one day during the winter months. Charity says, “I want my father to go

to the jail.” Her sister is so traumatized that she won’t leave Charity’s side

and only eats, sleeps, and speaks when Charity tells her it’s okay to do so.

Perpetual Kimanze, who takes care of these girls and coordinates their

counseling and therapy, keeps a close eye on Susan when the little girl begins

to talk to me in a barely audible voice, uttering each word with an agonizing

pause between, and says, “My … father … put … his … penis … between … my … legs

… and … he … hurt … me.”

It’s been six days since Emily was raped; she still complains of stomach pain.

She can’t sleep. She says in her native Kiswahili (a local dialect of Swahili),

“Nasikia uchungu sana nikienda choo, kukojoa.” It hurts to go to the bathroom.

Doreen, fifteen, has a four-month-old baby as a result of being raped by her

cousin. Her mother is mentally ill. Her father left them years ago, and they

had moved in with her mother’s sister. When Doreen realized she was pregnant,

her aunt told her to have an abortion; when her uncle found out, he beat her

and threw her out of the house. She was considering suicide when she heard

about Ripples and came to their Tumaini Centre.

In Kenya a girl child is raped every thirty minutes; some are as young as three

months old. If a girl doesn’t die of her injuries, she faces abandonment;

families don’t want anything to do with girls who have been sexually assaulted.

She almost certainly loses the chance to get an education. Some can’t go to

school anymore because they’ve been raped by the teacher. Others are prohibited

by the stigma; the girls are doubly victimized by being ostracized. They often

become HIV positive as a result of rape, so their health is compromised.

Urinary tract infections and sexually transmitted diseases plague them. Without

an education, with poor health and no means of financial support, the girls

drift into poverty. Their childhood is over and they become the face the world

expects of Africapoor, unhealthy, and destitute.

Twenty-five percent of Kenyan girls aged twelve to twenty-four lose their

virginity due to rape. An estimated 70 percent never report it to the

authorities, and only one-third of the reported cases wind up in court. If the

prosecutor can prove that a girl was under the age of fifteen when she was

assaulted, the rapist’s sentence is life in prison. But there’s the rub. The

laws are not enforced, and rape is on the rise. More than 90 percent know their

assailant: fathers, grandfathers, uncles, teachers, prieststhe very people

assigned the task of keeping vulnerable children safe. And raping little girls

as a way of cleansing themselves from HIV/AIDS isn’t the only reason they act.

Says Hedaya Atupelye, a social worker I met at the shelter run by the Women’s

Rights Awareness Program in Nairobi, “Men think having sex with a little girl

is a sign of being wealthy and stylish. Some of these men are educated beyond

the graduate level, but they want to be the first to break the flower so they

seek out young girls.”

If it’s the breadwinner who’s guilty, the family will go hungry if he’s sent

to jail, so even a child’s mother will choose to remain silent. “It’s our

African culture,” says Kimanze. “No one wants to associate with one who’s been

raped or who’s lived in a shelter. We need to stand up and say the shame isn’t

ours, it’s yours.”

In Kenya, people can pay to have their police charges disappear. Or they can

bribe a police officer and no charges will be brought. If the case is taken

seriously, statements are taken, the child is sent to a doctor for examination,

and the file with the doctor’s report is returned to the police. “This is also

where money changes hands,” says Atupelye. “If a girl, or for that matter a woman,

goes to the police on her own, she is usually ridiculed and harassed. It was

suggested half a dozen years ago that the police create a gender desk where a

female would be safe in reporting the crime, but invariably the gender desk

isn’t manned and is covered with dust.”

“One of the challenges is that our culture doesnt allow us to speak out about

sexual things,” says Mercy Chidi. “My only advice from my mother when I got my

period was ‘Don’t play with boys; you’ll get pregnant.’ My own uncle tried to

rape me, and to this day I have not told my mother. We have to break this

silence.” When the girls arrive at the shelter, she says, they are severely

traumatized and don’t want to talk to anyone. Some are frightened, others

aggressive. They tend to pick on one another. And as much as they come around

and begin to heal, Mercy says that they never completely overcome the trauma.

“It’s like tearing a paper into many pieces. No matter how carefully you try to

put the pieces together again, the paper will never be the same. That’s what

sexual assault does.” One little girl at the shelter begins to cry every night

when it starts to get dark and the curtains are drawn. “It’s the hour when her

father used to come and rape her,” Chidi says.

In the program at Tumaini Centre, the girls stay for six weeks; they receive

prophylaxis drugs to prevent HIV/AIDS and pregnancy as soon as they arrive and

medical care and counseling for the duration. If it isn’t safe for them to

return home, they go to a boarding school or stay on in the residence at the

center. Those who go home come back once a month for six months and then every

three months for ongoing counseling and support. When I visited, there were

eleven girls in residence.

One of them, a fifteen-year-old called Luckline, had been raped by a neighbor.

She was thirty-nine weeks pregnant when we met. When she talked about what had

happened to her, she didn’t sound like a victim. She sounded like a girl who

wanted to get even, to make a change. She said, “This happened to me on May 13,

2010. I will make sure this never happens to my sister.” When I asked what she

would do after the baby was born, she said she wanted to return to school

because she planned to become a poet. With little prompting, she read me one of

her poems.

Here I come

Walking down through history to eternity

From paradise to the city of goods

Victorious, glorious, serious, and pious

Elegant, full of grace and truth

The centerpiece and the masterpiece of literature

Glowing, growing, and flowing

Here, there, everywhere

Cheering millions every day

The book of books that I am.

This from a teenager who is disadvantaged in every imaginable way. Yet she

was preparing to sue her government for failing to protect her. This is how

change happens. But it takes commitment and colossal personal strength for a

girl to tackle the status quo and claim a better future for herself.

Back in Nairobi, I visit with Nano, a magistrate in the children’s court. She

insisted that her full name not be used, as she must be seen as totally

impartial both to the children and to the system that she criticizes. “The

difficulty,” she said, “is that the police lack knowledge of the law. Not all

but most need training and sensitization around sexual assault.” And, she said,

“It’s hard to get evidence from children; they need psychologists and

counselors to talk to them, and the Kenyan legal system simply doesn’t have

that resource. Even some magistrates lack training and knowledge of the Sexual

Offences Act.” Of the few cases that have made it to the court, she said, “The

difficulty is, they come without the information I need to convict. The girls

block it out or don’t turn up. There are all kinds of judicial tools I can use:

CEDAW [the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against

Women], the children’s convention, even the new Sexual Offences Act legislation

in Kenya. The investigating officer needs to tell the court what has been

found, the charge sheets have to be drafted correctly, and the child needs to

be able to tell the officer what happened; if she can, she needs to identify

the man who defiled her and say, ‘He is the one who did this to me.’ The

children have to be prepared for this. Without it, I cannot convict.”

After that conversation with the magistrate, I sat in on the meeting that the

team of lawyers was holding in a hotel across town. While diesel-belching buses

and the traffic chaos in Nairobi created cacophony outside, the lawyers

hunkered over their files at a long narrow table, creating a strategy for the

case. They debated the wording, parsing every sentence, nitpicking the legal

clauses, testing the jurisprudence. They knew it would take collaboration

between lawyers, doctors, and academics, experts in human rights law as well as

international law, to be successful. They also needed to protect the girls and

make sure they weren’t revictimized by the process. Once the child’s story has

been documented by an officer, the lawyer can make the accusation in court,

thus preventing the girls from being further traumatized.

For five long days, they argued over how best to make the case. There were

three choices: a civil claim, a criminal claim, or a constitutional claim.

Finally they decided that a constitutional challenge was the way to go. The

Kenyan constitution guarantees equality rights for citizens. It promises

protection for men and women. It governs the laws that deliver that protection.

The lawyers decided to argue that the state failed to execute the

constitutional rights of the girls. Then they set their sights on a court date.

The journey they were on together is about girls who dared to break the taboo

on speaking out about sexual assault. It’s about women lawyers from two sides

of the world supporting these youngsters in their quest for justice. It’s about

the kids who were told they had no rights but insist that they do. It’s the

push-back reaction that every woman and girl in the world has been waiting for.

“This case is the beginning,” said Chidi. “It’ll be a long journey, but now it

has begun.” The feeling as they prepared to go to court was if they won, the

victory would be a success for every girl and woman in Africa, maybe even the

world.

On October 11, 2012, when the case went to court in Meru, the lawyers marched

through the streets from the shelter where the girls had been staying to the

courthouse. The kids wanted to march as well but were told their identity

needed to be protected and they must stay back at the shelter. Nothing doing,

they said. They marched beside their advocates to the courthouse chanting,

“Haki yangu,” the Kiswahili words for “I demand my rights.” With all the

hullaballoo on the street, the police at the court panicked and slammed the

gates shut as the girls approached. Nothing would stop them now. They climbed

onto the fence still calling, “Haki yangu,” and then they looked at one another

and started to laugh at the reversal in roles being played out in front of

them. “Look,” they called to each other, “these men who hurt us and made us

ashamed are scared of us now.” Soon enough the gates were opened and the girls

and their lawyers entered the court to begin the proceedings that would alter

their future.

There was something deliciously serendipitous about the power going off in

northern Kenya seven months later on May 27, 2013, just as Judge J. A. Makau

read his much-anticipated decision about this case that put rape in a glaring

spotlight, a case that could alter the status of women and girls in Kenya and

maybe all of Africa. When the lights came on, the judge in the high court in

Meru, Kenya, stated: “By failing to enforce existing defilement [rape] laws,

the police have contributed to the development of a culture of tolerance for

pervasive sexual violence against girl children and impunity.”

Guilty.

The earth shifted under the rights of girls and women that day; the girls

secured access to justice for themselves and legal protection from rape for all

10 million girls and women in Kenya.

Within forty-eight hours of the court decision, Fiona Sampson had heard from

half a dozen other countries that want the same action. But “the win is only as

good as the justice each girl gets,” says Marcia Cardamore, whose PeopleSense

Foundation was the major funder of the court case. She underscores the need for

close follow-up when she says, “We sent a letter to the court to give three

months’ notice to the police that we need to see results or we’ll take more

action, put more legal pressure on them. Without due process, we haven’t won

anything.”

Marcia is part of a new generation of women philanthropists who are determined

to make changes. She belongs to an organization called Women Moving Millions

that was founded in 2005 by Helen LaKelly Hunt and her sister, former U.S.

ambassador to Austria Swanee Hunt, who understood that moving the bar for

women’s equality rights meant raising the financial stakes. “I get the sense I

am not an outlier and there are other women in the world who want to overcome

these injustices,” says Marcia. Like everyone else involved with this case,

she’s watching and ready to act if justice is not forthcoming.

* * *

The road they travel was paved by women who went before: those who were willing

to cry foul rather than be silenced by shame; those who worked tirelessly to

make the world understand that rape is not the right of men; those who insist

rape is not the “fault” of women but a control issue among men who have failed

to grasp the consequences of scarring a woman’s mind by assaulting her body.

Like so many issues that have reached a turning point for women, rape has gone

from being the crime no one wants to talk about, to making headlines, to being

a prominent subject in courts, in newly published books, and in award-winning

films. Among the first to go public on a world stage were the extraordinarily

brave women from Bosnia who went to the International Criminal Court in The

Hague in 1998; despite the very real possibility that they would be forever

rejected by their families, they testified about what had happened to them:

they had been rounded up, taken to enemy camps, and gang-raped.

Their story of sexual violence actually began when the USSR collapsed in 1991

and its sister state Yugoslavia (created at the end of the First World War from

seven independent nations) erupted in a civil war in the Balkans so virulent

that former neighbors, old friends, and business partners attacked one another

in a ferocious bloodbath that riveted the world’s attention. I began covering

the story soon after that, which is how I came to meet some of the women who had

been gang-raped. But getting their story published was a story in itself.

In the fall of 1992, I was in Sarajevo to cover the effect of war on children.

The siege of Sarajevo was like nothing I had ever seen before. Snipers and

soldiers were waging a war against civilians. Targets of the shelling were

hospitals, schools, and playgrounds. Explosives made in the shape of children’s

toys were maiming kids who picked them up. Families were forced to live in

basements while soldiers took over the rest of the house. And all this was

happening in a breathtaking setting, in a city that had played host to the

Olympic Games, in a region that was picture-postcard beautiful. The towns had

names that sound like songs. White stucco houses with red clay roofs dotted the

landscape.

The sun cast a glow on ancient hills that turned purple at dusk and glowed

buttery yellow at dawn. But the streets were rife with the Devil’s work, and

there was peril at every corner.

The day before I was to leave Sarajevo, I began to hear rumors about Bosnian

Serb soldiers who were rounding up Bosnian Muslim women and dragging them off

to rape camps. Every journalist knows that one of the first casualties of war

is the truth, and I thought that what I was hearing was propaganda. This was

two years before the horror of Rwanda, before Darfur, before Congo. But as the

day progressed, I kept hearing about the rape camps from more and more credible

sources. At that time, I was the editor in chief of a magazine, and magazines

have a much longer lead time than newspapers. If this story was true, it was

breaking news that needed to be published immediately; it couldn’t wait the

three months it would take to get it to my magazine readers.

I gathered everything I couldcell phone numbers, names, details about Muslim

wives and sisters and daughters being gang-raped eight and ten times a day.

When I flew back to Canada, I went straight to a media outlet and handed over

the file to an editor I knew. I said, “This is a horrendous story. Give it to

one of your reporters.” I went back to my office and waited for the headline.

Nothing. I waited another week and anotherstill nothing. Seven weeks later, I

saw a four-line blurb in Newsweek magazine about soldiers gang-raping women in

the Balkans. I called the editor I’d given the package to.

As soon as he heard my voice, he started to gigglenervously. “Oh, I knew you’d

be calling me today,” he said.

“What happened?” I wanted to know.

“Well, Sally,” he said, “it was a good story, but, you know, I got busy and, you

know, I was on deadline and, you know, I forgot.”

I was astounded. I said, “More than twenty thousand women were gang-raped, some

of them eight years old, some of them eighty years oldand you forgot?”

I hung up and called my staff together and told them what had happened. We

decided to do the story ourselves. I was on a plane back to the war zone two

days later.

Six women who were refugees in Zagreb, Croatia, were willing to be interviewed,

but they were reluctant to have their names used as they knew they’d be

rejected by their families if word of the rapes got out. While most women did

not become pregnant, some did. Of those who were pregnant, some managed to get

abortions; some had been kept in prison until abortion was impossible. And

still others had escaped but couldn’t find medical help in time for an

abortion. Many who gave birth left the newborns at the hospital. Mostly I

talked to frightened women who badly needed health care and counseling and were

too traumatized to share their stories. I worried about asking a woman to

relive the horror and began to wonder how to best tell a story that most

preferred to be silent about.

Then I met Dr. Mladen Loncar, a psychiatrist at the University of Zagreb, who

told me about a woman who was furious with the silence around this atrocity and

had plenty to say. He promised to call her and ask for an interview on my

behalf, and when he did, Eva Penavic said yes, she would talk to me. Getting to

her was a problem, though, as she was living as a refugee on the eastern border

between Bosnia and Croatia, near the city of Vukovar. The area was being

shelled day and night.

The photographer I drove with accelerated through towns where buildings were

still smoking from being hit by rocket-propelled grenades (and turned up the

volume on a Pavarotti CD to block out the sound of grenades exploding in the

distance). We finally arrived late in the afternoon at the four-room house Eva

was sharing with her extended family of seventeen. For the next seven hours, I

listened while she described the hideous ordeal she’d survived.

Eva told me that she thought the men pounding at her door in the little eastern

Croatian village of Berak in November 1991 had come to kill her. Rape was the

furthest thing from her mind when they shot off the hinges of her door. After

all, she was regarded as a leader in this village of eight hundred people. She

was forty-eight years old. She had five grandchildren.

Eva was a wise woman who knew that her sex didn’t guarantee her safety. She was

the child of a widow who had to leave home and find work in another village.

She was the niece of an abusive man who tried to force her into an arranged

marriage when she was sixteen. But despite all her girlhood experiences, she

could never have imagined the horror she’d be subjected to during the brutal

conflict in the former Yugoslavia.

Eva was one of the civil war’s first victims of mass gang rape. The crime

committed against her was part of a plan, a cruel adjunct to the campaign known

as “ethnic cleansing”a phrase as foul to language as the act is annihilating

to its victims. An estimated twenty thousand to fifty thousand women, mostly in

Bosnia and some in Croatia, shared Eva’s fate.

Historians claim that what happened there was worse than the rapes of opportunity

and triumph usually associated with war. This was rape that was organized,

visible, ritualistic. It was calculated to scorch the emotional earth of the

victim, her family, her community, her ethnic group. In many cases, the

victim’s husband, children, cousins, and neighbors were forced to watch.

In other cases, victims heard the screams of their sisters or daughters or

mothers as one after another was dragged away to be raped in another room.

Eva was canning tomatoes in a little stone pantry at the back of her house when

her door splintered open and twelve men rushed in, subdued her, and blindfolded

her. Hissing profanities in her ear, they bullied her out the door and beat her

about her legs as she stumbled along a path to a neighboring house, which an

extremist Serbian group known as the White Eagles had moved into just the week

before.

Born of Croatian parents, Eva knew every house in her home village, every

garden, the configuration of the town center, every bend of the creek that

flowed around it. Her lifelong best friend, Mira (her name has been changed),

was Serbian. As children, they spent their days chasing geese through the

middle of town to the Savak Creek. The game was always the same, the kids

shrieking wildly as they chased baby geese, with the big geese in hot pursuit

of the kids. Eva became a sprinter of such caliber that she was selected to

represent first her village, then her district in regional track meets.

As a young woman, she fell in love with a man named Bartol Penavic, and on

November 17, 1958, they were married. Together they raised three children, saw

them married and settled, and in time became grandparents. Life was good.

The countryside surrounding the village resembles a mural crayoned by

childrena clutch of clay-colored houses here, a barn there. On one side of the

village stretches a patchwork of rolling hills and thick oak forest so green

and purple and yellow that the colors could have been splashed there by

rainbows; on the opposite side is flat black farmland with hedgerows of

venerable old trees. The town itself is an antique treasure, a

three-hundred-year-old tableau of muted colors and softly worn edgesas

unlikely a setting for ugliness as could be imagined.

By the time spring began to blossom in 1991, Croatia had declared its

independence from Yugoslavia and there were rumblings of trouble. But no one

paid much attention. Eva said, “We’d lived togetherCroats and Serbs and

Muslimsfor fifty years. How could anyone change that?” Bartol had told her,

“Now is the time for us. Our children are settled. It’s time for us to enjoy

life.” They’d had their share of grief: Eva’s father had been killed during the

Second World War, and the uncle who assumed charge of her was appalled that she

dared to choose the man she would marry. Bartol’s family saw Eva as a peasant,

hardly a match for the son of the biggest landowner in the surrounding

villages. Despite the odds against them, their thirty-three-year marriage had

been rich with the promise of happily-ever-after.

Then in the fall, barricades appeared on the street. As a precaution, they sent

their daughter and two daughters-in-law away with the grandchildren to a safer

place. Soon enough, the village was under siege. Their sons managed to escape

as tanks rolled into town. Most villagers ran away; those who didn’t, including

Eva and Bartol, were rounded up and kept in detention. The interrogations and

beatings began. Bartol was beaten to death. Eva was sent home by the commander

and told to stay in the pantry at the back of the house.

Then the men came for her. They said they were taking her to another village

for interrogation, but she knew precisely where they were goingto the nearby

house where the White Eagles were headquartered. At the door, her captors

announced to the others, “Open upwe bring you the lioness.” Once she was

inside, they attacked her like a pack of jackals. Six men stripped her, then

raped her by turns, orally and vaginally. They urinated into her mouth. They

screamed that she was an old woman and if she was dry they’d cut her vagina

with knives and use her blood to make her wet. She was choking on semen and

urine and couldn’t breathe. The noise was horrendous as the six men kept

shrieking at her that there were twenty more men waiting their turn and calling

out, “Who’s next?” She was paralyzed with fear and with excruciating pain. The

assault continued relentlessly for three hours.

When they were finished, they cleaned themselves off with her underwear and

stuffed the fouled garments into her mouth, demanding she eat them. Then they

marched her outside into the garden. She could hear the village dogs barking.

She knew exactly where she was and she knew that the cornfield they were

pushing her toward was mined. Still blindfolded, she was thrust into the field

and told to run away. She stumbled through the slushy snow and sharp

cornstalks, and when she was far enough away from the house, she ripped the

blindfold off. Injuries from the rape slowed her down, but she was fast all the

same. Then she slipped in the muddy field and fell, and at exactly that moment,

bullets ripped over her head. She flattened herself into the mud as she heard

the cheers of the terrorists, who thought they had bagged another kill. She

waited a long time before getting to her feet and staggering on, and then

wandered for three more hours, trying to focus, to think of a way to survive.

Finally she stumbled into her neighbor’s garden.

Mira had been waiting by the window all night, knowing her childhood friend had

been taken away. When she heard the rustle in the garden, she rushed outside

with her husband, and together they gathered up their battered friend. Mira

bathed Eva, made her strong tea, and cradled her head while she vomited the

wretched contents of her stomach and then collapsed. The next morning, Eva left

the village. She didn’t come back until the conflict was over.

I visited her again during the war and after the war was over, as well.

Although she had reunited with her family and together they returned to Berak,

the men responsible for the crime were still roaming the streets of her

village, still gloating when Eva walked by. The last time I saw her, in 2005,

she told me she still wonders why she was spared. Cradling a new grandchild in

her arms, she repeated the comment she’d made when I left her in 1991: “I’ve

always wondered why God didn’t take me when he took my Bartol. I think I must

have been left here to be the witness for the women.”

It took me the usual three months to get the story to our readers. But after it

was published, they took up the torch for these women, and in the form of

thousands of letters to the editor, they demanded that the United Nations do

something about it.

This was rape as a form of genocide. In the rape camps, many Bosnian women

were assaulted until they became pregnant. The Serbian soldiers, known as

Chetniks, viewed systematic rape as a way of planting Serbian seeds into

Bosnian women and therefore destroying their ethnicity and culture. It wasn’t

enough that the women felt their families would reject them because they had

been raped, a shame to Islam. The women’s suffering was twofold, just like that

of the women of Rwanda and Congo in the years that would follow.

I often wondered what made Eva tell her story when others were too afraid to

speak. She told me that in her opinion, the vanquished need a face and a name.

Atrocities need a date and a time. Telling the truth is the only way to heal.

“It’s not enough to say, ‘You raped me,’” she said. “When I say it happened,

where it happened, and what my name is, it makes the rape something to be

responsible for.”

But even with worldwide attention on the mass rape of women in the Balkans, and

the enormous pity for them and fury for the perpetrators that resulted, the

stigma of being raped stuck to those women. One of the problems with stopping

the scourge of rape in zones of conflict is eradicating that stigma. What

everyone needs to understand is that these women and girls are just like

everybody’s mothers and daughters. They are women who had jobs to go to,

mortgages to pay; their children, just like the children of their rapists, just

like our children, also got croup and forgot to do their homework or ducked out

of doing family chores. They had friends over for dinner, took holidays, went

to the park, watched over their kids on the swings, the seesaws, the jungle

gyms.

But somehow when we hear stories like Eva’s or stories about the women in

Rwanda or Congo, we turn the victims and their attackers into “others.” We

listen to foolish remarks such as “They’ve been at this for centuries; let them

kill each other.” Or “They always treat their women like this; it’s not my

business.” Perhaps it’s a way of separating ourselves from something we feel

powerless to stop. But we do have power. We can write letters to the United

Nations to demand action. We can speak up when others dismiss these atrocities

as cultural or religious or worsenone of our business. It took a brave

collection of women from Bosnia to do something about rape. They took their dreadful

stories to the International Criminal Court in The Hague. They risked being

rejected by their families by telling their stories to the world. But they gave

the international tribunal the tools to do what courts and governments have

avoided throughout history. It made rape a war crime. In 1998, the Yugoslavia

War Crimes Tribunal, also in The Hague, made rape and sexual enslavement in the

time of war a crime against humanity. Only genocide is considered a more

serious crime.

* * *

I believe the shift in thinking about the role of women and the issues that

women deal with in the first decade of the third millennium will go down in

history as a turning point for civilization. Issues such as sexual assault that

had been buried, denied, and ignored suddenly began to be explored in

groundbreaking research papers and to figure in legislative reform.

Two books published in the spring of 2011 brought facts to light that might

have put the international community on alert against the mass rape in Bosnia,

Rwanda, and Congo. In one of them, At the Dark End of the Street, Danielle

McGuire exposed a secret that had been held for sixty-five years. It’s the

story of the iconic Rosa Parks, the tiny, stubborn woman who defied the Jim

Crow segregation rules in Montgomery, Alabama, when she refused to comply with

a white man’s order to move to the back of the bus. That solitary act of

defiance was the catalyst that in 1955 gave rise to the civil rights movement.

But McGuire’s research brings out a more astonishing piece of the story. For

ten years prior to her famous bus boycott, Rosa Parks was an antirape activist.

Parks began investigating rape in 1944, collecting evidence that exposed a

ritualized history of sexual assault against black women. That evidence was ignored.

All these decades later, McGuire is the first to tell what she calls “the real

storythat the civil rights movement is also rooted in African-American women’s

long struggle against sexual violence.” And she argues that given the role rape

played in the lives of womenthat it was ongoing, that it fueled the anger and

powered the movement as much as the Jim Crow laws didthe history of the civil

rights movement needs to be rewritten. She sees the infamous Montgomery bus

incident as an event that was as much about women’s rights as about civil

rights. As McGuire eloquently writes, “It was a women’s movement for dignity,

respect and bodily integrity.”

Gloria Steinem agrees. In a review of McGuire’s book, Steinem wrote, “Rosa

Parks’ bus boycott was the end of a long process that is now being taken

seriously. What Rosa Parks did was expose [to the leaders of the civil rights

movement] the truth about sexual assault as well as the widespread ugliness of

rape as a tool to repress, punish and control women during the civil rights

movement. Her work was meant to be a call for change in America. And yet until

the fall of 2011, hardly anyone even knew about it.” Why didn’t we know this

before? Why has so much history involving women been either ignored or suppressed?

How is it that the stunning facts Rosa Parks gathered were never published at

the time? And would the world have changed had the information been available

sooner?

The rape of black women as an everyday practice of white supremacy wasn’t the

only revelation in 2011. The other book, Sexual Violence against Jewish Women

during the Holocaust, is a collection of essays edited by Sonja Hedgepeth, a

professor at Middle Tennessee State University, and Rochelle Saidel, executive

director of the U.S.-based Remember the Women Institute. As I read the book, I

had to put it down from time to time to catch my breath. With all the

documentation and literature of the Holocaust, all the memorials and reminders,

how can it be that this appalling information about the gang-raping and sexual

abuse of Jewish women has been left out until now? No one knows how many women

and girls were sexually assaulted while they were isolated in ghettos or

incarcerated in concentration camps, and no one ever will. Some women were

murdered, and others chose to remain silent, as rape carries a stigma even in

the chambers of death: even though a woman was raped, she was “having sex” with

the enemy. The authors refer to this kind of shame as the most effective of all

social weapons. And they say that women caught in war zones invariably face “a

dilemma of fatal inclusion or unbearable ostracism.”

The men who raped these women in Nazi concentration camps were obsessive about

keeping recordsof inhuman medical experiments performed, of the elimination of

men, women, and children in the gas chambers or by shooting or hanging. But

they kept no list of who was raped. There is not a word in the vast accountings

of the Nazi regime about the sexual assault of women and girls. The story is

simply missing. Seen as sexual objects as well as a biological danger by the

Nazis, Jewish women were the target of sexual depravity and rape. And yet their

story was suppressed. As the essays in this important book show, the survivors

shared details before the trials at Nuremburg, but not a word was spoken during

the trials.

In an interview with me, Gloria Steinem said, “The judges at Nuremberg didn’t

want crying women in the courtroom. And some Jewish historians didn’t want to

admit their women had been sexually assaulted and/or denied it had happened.

It’s taken sixty years for that to come out.” She believes that the floodgates

began to open when rape became a war crime and told me that women owe a debt of

gratitude to Navi Pillay, the judge who made that historic ruling at the

International Criminal Court. Because of her, and the recent work of other

scholars and activists in the public sphere, the crime of rape is no longer

seen as either inevitable or the fault of women.

“Think about Bosnia, Rwanda, and Congo,” Steinem said. “If we had acknowledged

what happened to Jewish women in the Holocaust or black women in the civil

rights movement, we’d have been better prepared for what happened in Bosnia,

Rwanda, and Congo. It’s not about war, it’s about genocide. To make the right

sperm occupy the wrong womb is an inevitable part of genocide. The publication

of these books is a warning to the world that sexual violence is a keystone to

genocide, and they make it clear that today there’s a shift in the sense that

rape is now noticed and even taken seriously. That wasn’t true before.”

As the researcher Brigitte Halbmayr points out in Sexual Violence against

Jewish Women during the Holocaust, “Unlike the cases in Rwanda and former

Yugoslavia, where rape was used as a strategy of war, sexualized violence was

not an inherent part of the genocidal process during the Holocaust. Instead, it

was part of the continuum of violence that resulted from genocide. Rape was not

an instrument of genocide, but was the byproduct of intentional annihilation.”

Like the judges at Nuremburg, film directors and publishers have hesitated to

expose the brutal truth about rape. But that too is changing. Lynn Nottage was

awarded the 2009 Pulitzer Prize for Drama for her play, aptly titled Ruined,

which chronicles the plight of women in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The Pulitzer citation hailed Ruined as “a searing drama set in chaotic Congo

that compels audiences to face the horror of wartime rape and brutality while

still finding affirmation of life and hope amid hopelessness.” The play tells

the story of Mama Nadi, the proprietor of a local establishment that acts both

as a shelter for women who’ve been damaged or “ruined” by the civil war and a

bar/brothel for the nationalist and rebel soldiers who keep it raging on.

Always the shrewd businesswoman, Nadi sides neither with the women she shelters

nor with her militant patrons until the war outside closes in and there are

choices to make and truths to face.

Two years later, a film called Incendies (Scorched) became another example of

the new truth-telling. Adapted from a play by Wajdi Mouawad, a

Lebanese-Canadian writer, and directed by the Quebec filmmaker Denis

Villeneuve, it was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language

Film in 2011, even though it takes the audience where few have dared to go

before with a story in which twins fulfill their mother’s dying wish. They

travel to the Middle East, where they discover they were born of rape by the

man who ran the prison where their mother was incarcerated. That man turns out

to be their brother as well as their father. It is a searing and courageous

tale of the humiliation of rape, the will to survive, and the scorched-earth

patterns of rapists.

Whether committed inside or outside a war zone, rape punishes women twice.

First they suffer the physical abuse and then the never-ending memory and

shame, which threaten and retreat like tidal surges throughout the rest of

their lives. Justice can only come from acknowledgment and the conviction of

the perpetrator.

That’s what the girls in Kenya were counting on. And when the judge vindicated

them in May 2013, magistrates from around the world were buffeted by the hot

winds of change that blew out of Africa.

Copyright © 2013, 2014 by Sally Armstrong