WUNRN

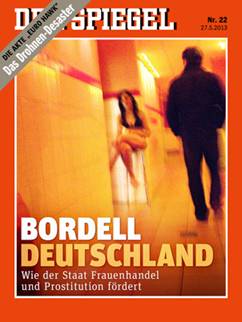

GERMANY - DEBATE ON CONTINUED

LEGALIZATION OF PROSTITUTION

Sânandrei

is a poor village in Romania with run-down houses and muddy paths. Some 80

percent of its younger residents are unemployed, and a family can count itself

lucky if it owns a garden to grow potatoes and vegetables.

Alina

is standing in front of her parents' house, one of the oldest in Sânandrei,

wearing fur boots and jeans. She talks about why she wanted to get away from

home four years ago, just after she had turned 22. She talks about her father,

who drank and beat his wife, and sometimes abused his daughter, too. Alina had

no job and no money.

Through

a friend's new boyfriend, she heard about the possibilities available in

Germany. She learned that a prostitute could easily earn €900 ($1,170) a month

there.

Alina

began thinking about the idea. Anything seemed better than Sânandrei. "I

thought I'd have my own room, a bathroom and not too many customers," she

says. In the summer of 2009, she and her friend got into the boyfriend's car

and drove through Hungary, Slovakia and the Czech Republic until they reached

the German capital -- not the trendy Mitte neighborhood in the heart of the

city, but near Schönefeld airport, where the name of the establishment alone

said something about the owner: Airport Muschis ("Airport Pussies").

The brothel specialized in flat-rate sex. For €100 ($129), a customer could

have sex for as long and as often as he wanted.

It

all went very quickly, says Alina. There were other Romanians there who knew

the man who had brought them there. She was told to hand over her clothes and

was given revealing lingerie to wear instead. Only a few hours after her

arrival, she was expected to greet her first customers. She says that when she

wasn't nice enough to the clients, the Romanians reduced her wages.

The

Berlin customers paid their fee at the entrance. Many took drugs to improve

sexual performance and could last all night. A line often formed outside

Alina's room. She says that she eventually stopped counting how many men got

into her bed. "I blocked it out," she says. "There were so many,

every day."

Locked Up

Alina

says that she and the other women were required to pay the pimps €800 a week.

She shared a bed in a sleeping room with three other women. There was no other

furniture. All she saw of Germany was the Esso gas station around the corner,

where she was allowed to go to buy cigarettes and snacks, but only in the

company of a guard. The rest of the time, says Alina, she was kept locked up in

the club.

Prosecutors

learned that the women in the club had to offer vaginal, oral and anal sex, and

serve several men at the same time in so-called gangbang sessions. The men

didn't always use condoms. "I was not allowed to say no to anything,"

says Alina. During menstruation, she would insert sponges into her vagina so

that the customers wouldn't notice.

She

says that she was hardly ever beaten, nor were the other women. "They said

that they knew enough people in Romania who knew where our families lived. That

was enough," says Alina. When she occasionally called her mother on her

mobile phone, she would lie and tell her how nice it was in Germany. A pimp

once paid Alina €600, and she managed to send the money to her family.

Alina's

story is not unusual in Germany. Aid organizations and experts estimate that

there are up to 200,000 working prostitutes in the country. According to

various studies, including one by the European Network for HIV/STI Prevention

and Health Promotion among Migrant Sex Workers (TAMPEP), 65 to 80 percent of

the girls and women come from abroad. Most are from Romania and Bulgaria.

The

police can do little for women like Alina. The pimps were prepared for raids,

says Alina, and they used to boast that they knew police officers. "They

knew when a raid was about to happen," says Alina, which is why she never

dared to confide in a police officer.

The

pimps told the girls exactly what to tell the police. They should say that they

were surfing the web back home in Bulgaria or Romania and discovered that it

was possible to make good money by working in a German brothel. Then, they had

simply bought themselves a bus ticket and turned up at the club one day,

entirely on their own.

Web of Lies

It

seems likely that every law enforcement officer who works in a red-light

environment hears this same web of lies over and over again. The purpose of the

fiction is to cover up all indications of human trafficking, in which women are

brought to Germany and exploited there. It becomes a statement that transforms

women like Alina into autonomous prostitutes, businesswomen who have chosen

their profession freely and to whom Germany now wishes to offer good working

conditions in the sex sector of the service industry.

That's

the 'respectable whore' image politicians seem in thrall of: free to do as they

like, covered under the social insurance system, doing work they enjoy and

holding an account at the local savings bank. Social scientists have a name for

them: "migrant sex workers," ambitious service providers who are

taking advantage of opportunities they now enjoy in an increasingly unified

Europe.

In

2001, German parliament, the Bundestag, with the votes of the Social Democratic

Party/Green Party governing coalition in power at the time, passed a

prostitution law intended to improve working conditions for prostitutes. Under

the new law, women could sue for their wages and contribute to health,

unemployment and pension insurance programs. The goal of the legislation was to

make prostitution a profession like that of a bank teller or dental assistant,

accepted instead of ostracized.

The

female propagandists of the autonomous sex trade were very pleased with

themselves when the law was passed. Then Family Minister Christine Bergmann

(SPD) was seen raising a glass of champagne with Kerstin Müller, Green Party

parliamentary floor leader at the time, next to Berlin brothel operator

Felicitas Weigmann, now Felicitas Schirow. They were three women toasting the

fact that men in Germany could now go to brothels without any scruples.

Today

many police officers, women's organizations and politicians familiar with

prostitution are convinced that the well-meaning law is in fact little more

than a subsidy program for pimps and makes the market more attractive to human

traffickers.

Strengthening the Rights of Women

When

the prostitution law was enacted, the German civil code was also amended. The

phrase "promotion of prostitution," a criminal offence, was replaced

with "exploitation of prostitutes." Procurement is a punishable

offence when it is "exploitative" or "dirigiste." Police

and public prosecutors are frustrated, because these elements of an offence are

very difficult to prove. A pimp can be considered exploitative, for example, if

he collects more than half of a prostitute's earnings, which is rarely possible

to prove. In 2000, 151 people were convicted of procurement, while in 2011 it

was only 32.

The

aim of the law's initiators was in fact to strengthen the rights of the women,

and not those of the pimps. They had hoped that brothel operators would finally

take advantage of the opportunity to "provide good working conditions

without being subject to prosecution," as an appraisal of the law for the

Federal Ministry for Families reads.

Before

the new law, prostitution itself was not punished, but it was considered

immoral. The authorities tolerated brothels, euphemistically referring to them

as "commercial room rental." Today, just over 11 years after

prostitution was upgraded under the 2001 law, there are between 3,000 and 3,500

red-light establishments, according to estimates by the industry association

Erotik Gewerbe Deutschland (UEGD). The Ver.di public services union estimates

that prostitution accounts for about €14.5 billion in annual revenues.

There

are an estimated 500 brothels in Berlin, 70 in the smaller northwestern city of

Osnabrück and 270 in the small southwestern state of Saarland, on the French

border. Many Frenchmen frequent brothels in Saarland. Berlin's Sauna Club

Artemis, located near the airport, attracts many customers from Great Britain

and Italy.

Travel

agencies offer tours to German brothels lasting up to eight days. The outings

are "legal" and "safe," writes one provider on its

homepage. Prospective customers are promised up to 100 "totally nude

women" wearing nothing but heels. Customers are also picked up at the

airport and taken to the clubs in a BMW 5 Series.

Flat-Rate Horror

In addition to so-called

nudist or sauna clubs, where the male customers wear a towel while the women

are naked, large brothels have also become established. They advertise their

services at all-inclusive rates. When the Pussy Club opened near Stuttgart in

2009, the management advertised the club as follows: "Sex with all women

as long as you want, as often as you want and the way you want. Sex. Anal sex.

Oral sex without a condom. Three-ways. Group sex. Gang bangs." The price:

€70 during the day and €100 in the evening.

According

to the police, about 1,700 customers took advantage of the offer on the opening

weekend. Buses arrived from far away and local newspapers reported that up to

700 men stood in line outside the brothel. Afterwards, customers wrote in

Internet chat rooms about the supposedly unsatisfactory service, complaining

that the women were no longer as fit for use after a few hours.

The

business has become tougher, says Nuremberg social worker Andrea Weppert, who

has worked with prostitutes for more than 20 years, during which the total

number of prostitutes has tripled. According to Weppert, more than half of the

women have no permanent residence, but instead travel from place to place, so

that they can earn more money by being new to a particular city.

Today

"a high percentage of prostitutes don't go home after work, but rather

remain at their place of work around the clock," a former prostitute using

the pseudonym Doris Winter wrote in a contribution to the academic series

"The Prostitution Law." "The women usually live in the rooms

where they work," she added.

In

Nuremberg, such rooms cost between €50 and €80 a day, says social worker

Weppert, and the price can go up to €160 in brothels with a lot of customers.

Working conditions for prostitutes have "worsened in recent years,"

says Weppert. In Germany on the whole, she adds, "significantly more

services are provided under riskier conditions and for less money than 10 years

ago."

Dropping Prices

Despite

the worsening conditions, women are flocking to Germany, the largest

prostitution market in the European Union -- a fact that even brothel owners

confirm. Holger Rettig of the UEGD says that the influx of women from Romania

and Bulgaria has increased dramatically since the two countries joined the EU.

"This has led to a drop in prices," says Rettig, who notes that the

prostitution business is characterized by "a radical market economy rather

than a social market economy."

Munich

Police Chief Wilhelm Schmidbauer deplores the "explosive increase in human

trafficking from Romania and Bulgaria," but adds that he lacks access to

the necessary tools to investigate. He is often prohibited from using telephone

surveillance. The result, says Schmidbauer, "is that we have practically

no cases involving human trafficking. We can't prove anything."

This

makes it difficult to track down those who bring fresh product from the most

remote corners of Europe for Germany's brothels, product like Sina. She told

the psychologists in the office of the women's information center in Stuttgart

about her path to German flat-rate brothels. In Corhana, her native village

near Romania's border with the Republic of Moldova, most houses have no running

water. Sina and the other village girls used to fetch water from the well every

day. It was like a scene out of "Cinderella." All the girls dreamed

that a man would come one day to rescue them from their gloomy lives.

The

man, who eventually drove up to the village well in his big BMW, was named

Marian. For Sina it was love at first sight. He told her that there was work in

Germany, and her parents signed a form allowing her, as a minor, to leave the

country. On the trip to Schifferstadt in the southwestern state of

Rhineland-Palatinate, he gave Sina alcohol and slept with her.

Marian

delivered her to the "No Limit," a flat-rate brothel. Sina was only

16, and she allegedly served up to 30 customers a day. She was occasionally

paid a few hundred euros. Marian, worried about police raids, eventually sent

her back to Romania. But she returned and continued to work as a prostitute.

She hoped that a customer would fall in love with her and rescue her.

'No Measurable Improvements'

Has

Germany's prostitution law improved the situation of women like Sina? Five

years after it was introduced, the Family Ministry evaluated what the new

legislation had achieved. The report states that the objectives were "only

partially achieved," and that deregulation had "not brought about any

measurable actual improvement in the social coverage of prostitutes."

Neither working conditions nor the ability to exit the profession had improved.

Finally, there was "no solid proof to date" that the law had reduced

crime.

Hardly

a single court had heard a case involving a prostitute suing for her wages.

Only 1 percent of the women surveyed said that they had signed an employment

contract as a prostitute. The fact that the Ver.di union had developed a

"sample employment contract in the field of sexual services" didn't

change matters. In a poll conducted by Ver.di, a brothel operator said that she

valued the prostitution law because it reduced the likelihood of raids. In

fact, she said, the law was more advantageous for brothel operators than

prostitutes.

To

operate a mobile snack bar in Germany, one has to be in compliance with the DIN

10500/1 standard for "Vending Vehicles for Perishable Food," which

states, for example, that soap dispensers and disposable towels are required. A

brothel operator is not subject to any such restrictions. All he or she has to

do is report to authorities when the brothel is opened.

Prostitutes

still avoid registering with authorities. In Hamburg, with its famous

Reeperbahn red-light district, only 153 women are in compliance with

regulations and have registered with the city's tax office. The government

wants prostitutes to pay taxes. Does it have to establish rules for the

profession in return?

The

odd role the government assumes in the sex trade is in evidence among street

hookers in Bonn. Every evening, prostitutes have to buy a tax ticket from a

machine, valid until 6 a.m. the next day. The ticket costs €6.

A Big Mac for Sex

In

the northern part of Cologne, where drug-addicted prostitutes work along

Geestemünder Strasse not far from the Ford plant, no taxes are levied. As part

of a social project, so-called "working stalls" -- essentially walled

off parking spots for car sex -- are built into a space under a shed roof.

Although there are no signs plainly indicating that the facility is for

prostitution, a speed limit of 10 kilometers per hour is posted for the fenced

area, and drivers are required to move in a counter-clockwise direction.

On

a cold spring evening, about 20 women are standing along the edge of the area.

Some have brought along camping chairs while others are sitting in repurposed

bus shelters. When a john has agreed on a price with one of the women, he takes

her to one of the stalls. There are eight of the stalls under the shed roof, as

well as a separate room for cyclists and pedestrians, with a concrete floor and

a park bench. There is an alarm button in each stall, and a Catholic women's

social service group monitors the area every evening.

Alia,

a 23-year-old in a blonde wig, has squeezed herself into a corsage and she is

trying to cover up the alcohol on her breath with a mint. Referring to herself

and the other street prostitutes, Alia says: "People who work here have a

real problem."

Alia's

path to Geestemünder Strasse began when she dropped out of school and moved in

with a boyfriend, who sent her out to turn tricks. She began working as a

prostitute because of "financial difficulties and love," she says,

and soon marijuana, cocaine, amphetamines and alcohol came into the mix.

"There is no prostitution without coercion and distress," she says.

She has been walking the streets for three years. "A woman who is doing

well doesn't work like this," she says.

The

going rate for oral sex and intercourse used to be €40 on Geestemünder Strasse.

But when the nearby city of Dortmund closed its streetwalking area, more women

came to Cologne, says Alia. "There are more and more women now, and they

drop their prices so that they'll make something at all," she complains.

Bulgarian and Romanian women sometimes charge less than €10, she says.

"One woman here will even do it for a Big Mac."

Germany's Human Trafficking Problem

But women from Eastern

Europe hardly work on Geestemünder Strasse. They have been driven away by

regular police passport checks, which were in fact intended to find and protect

victims of human trafficking and forced prostitution. Now the girls work the

street in the southern part of Cologne, but this still brings down prices in

the northern neighborhood.

In

2007 Carolyn Maloney, a Democratic Congresswoman from New York and founder of

the Human Trafficking Caucus in the United States Congress, wrote about the

consequences of the legalization of prostitution in and around the gambling

mecca of Las Vegas. "Once upon a time," she wrote, "there was

the naive belief that legalized prostitution would improve life for

prostitutes, eliminate prostitution in areas where it remained illegal and

remove organized crime from the business. Like all fairy tales, this turns out

to be sheer fantasy."

German

law enforcement officers working in red-light districts complain that they are

hardly able to gain access to brothels anymore. Germany has become a

"center for the sexual exploitation of young women from Eastern Europe, as

well as a sphere of activity for organized crime groups from around the

world," says Manfred Paulus, a retired chief detective from the southern

city of Ulm. He used to work as a vice detective and now warns women in

Bulgaria and Belarus against being lured to Germany.

Statistically

speaking, Germany has almost no problem with prostitution and human

trafficking. According to the Federal Criminal Police Office (BKA), there were

636 reported cases of "human trafficking for the purpose of sexual

exploitation" in 2011, or almost a third less than 10 years earlier.

Thirteen of the victims were under 14, and another 77 were under 18.

There

are many women from EU countries "whose situation suggests they are the

victims of human trafficking, but it is difficult to provide proof that would

hold up in court," reads the BKA report. Everything depends on the women's

testimony, the authors write, but there is "little willingness to cooperate

with the police and assistance agencies, especially in the case of presumed

victims from Romania and Bulgaria." And when women do dare to say

something, their statements are "often withdrawn."

Declining Convictions

A

study by the Max Planck Institute for Foreign and International Criminal Law

concluded that official figures on human trafficking say "little about the

actual scope of the offence."

According

to a report on human trafficking recently presented by European Commissioner

for Home Affairs Cecilia Malmström, there are more than 23,600 victims in the

EU, and two-thirds of them are exploited sexually. Malmström, from Sweden, sees

indications that criminal gangs are expanding their operations. Nevertheless,

she says, the number of convictions is declining, because police are

overwhelmed in their efforts to combat trafficking. She urges Germany to do

more about the problem.

But

what if the German prostitution law actually helps human traffickers? Has the

law in fact fostered prostitution and, along with it, human trafficking?

Axel

Dreher, a professor of international and development politics at the University

of Heidelberg, has attempted to answer these questions, using data from 150

countries. The numbers were imprecise, as are all statistics relating to trafficking

and prostitution, but he was able to identify a trend: Where prostitution is

legal, there is more human trafficking than elsewhere.

Most

women who come to Germany to become prostitutes are not kidnapped on the street

-- and most do not seriously believe that they'll be working in a German

bakery. More commonly, they are women like Sina, who fall in love with a man

and follow him to Germany, or like Alina, who know that they are going to

become prostitutes. But they often don't know how bad it can get -- and they

are unaware that they will hardly be able to keep any of the money they earn.

Some

cases are even more disturbing. In December, German TV audiences were shocked

by the show "Wegwerfmädchen" ("Disposable Girls"), part of

the "Tatort" crime series, filmed in the northern German city of

Hanover. It depicts pimps throwing two severely injured young women into the

trash after a sex orgy. Just a few days after the episode aired, Munich police

found a whimpering, scantily clad girl in a small park.

The Isar Dungeon

The

18-year-old Romanian had fled from a brothel. She told the officers that three

men and two women had approached her on the street in her native village. The

strangers had promised her a job as a nanny. When they arrived in Munich, she

said, they blindfolded her and took her to a basement cell with a door that

could only be opened with a security code.

Another

girl was sitting on a bunk bed in the dark room, she said, and there was the

sound of running water behind the walls. The police assume that the hiding

place was in an empty factory near the Isar River, which flows through Munich.

The men raped her and, when she refused to work in a brothel, they beat her,

she said.

The

officers were dubious at first, but the girl had remembered the pimps' names.

They were arrested and are now in custody. Because they refuse to answer

questions, the eerie dungeon still hasn't been found and the Romanian woman is

now in the witness protection program.

Sometimes

girls are sent by their own families, like Cora from Moldova. The 20-year-old

digs her hands into the pockets of her hoodie, and she is wearing plush

slippers with big eyes sewn to them. Cora lives in a hostel run by a Romanian

assistance center for victims of human traffickers. When girls in Moldova are

15 or 16, says Cora's psychologist, their brothers and fathers often say to

them: "Whore, go out and make some money."

Cora's

brothers took their attractive and well-behaved sister to a disco in the

nearest city. Her only duty there was to serve drinks, but she met a man there

with contacts in Romania. "He said that I could make a lot more money in

the discos there." Cora went with him, first to Romania and then to

Germany.

'Process of Emancipation'

After

being raped for an entire day in Nuremberg, she says, she knew what she had to

do. She worked in a brothel on Frauentormauer, one of Germany's oldest

red-light districts. She received the men in her room, allegedly for up to 18

hours a day. She says that police officers also came to the brothel -- as

customers. "They didn't notice anything. Or else they didn't care."

The

brothel was very busy on Christmas Eve 2012. Cora says that her pimp demanded

that she work a 24-hour shift, and that he stabbed her in the face with a knife

when she refused. The wound was bleeding so profusely that she was allowed to

go to the hospital. A customer whose mobile phone number she knew helped her

flee to Romania, where Cora filed charges against her tormentor. The pimp

called her recently, she says, and threatened to track her down.

Despite

stories like these, politicians in Berlin feel no significant pressure to do

anything. This is partly because, in the debate over prostitution, an

ideologically correct position carries more weight than the deplorable

realities. For example, when the Hamburg University of Applied Sciences held a

conference on prostitution in Germany a year ago, an attendee said that

prostitution, "as a recognized sex trade, is undergoing a process of

emancipation and professionalization."

Such

statements are shocking to Rahel Gugel, a law professor. "That's absurd.

It has nothing to do with reality," she says. A professor of law in social

work at the Baden-Württemberg Cooperative State University, Gugel wrote her

dissertation on prostitution law and has worked for an aid organization.

Proponents

of legalization argue that everyone has the right to engage in whatever

profession he or she chooses. Some feminists even praise prostitutes for their

emancipation, because, they say, women should be able to do what they want with

their bodies. In practice, however, it becomes clear how blurred the boundaries

are between voluntary and forced prostitution. Did women like Alina and Cora

become prostitutes voluntarily, and did they make autonomous decisions?

"It is politically correct in Germany to respect the decisions of

individual women," says lawyer Gugel. "But if you want to protect

women, this isn't the way to do it."

Berlin's Erroneous Approach

According to Gugel, many

women are in emotional or economic predicaments. There is evidence that a

higher-than-average number of prostitutes were abused or neglected as children.

Surveys have shown that many can be considered traumatized. Prostitutes suffer

from depression, anxiety disorders and addiction at a much higher rate than the

general population. Most prostitutes have been raped, many of them repeatedly.

In surveys, most women say that they would get out of prostitution immediately

if they could.

Of

course, there are also those women who decide that they would rather sell their

bodies than stock supermarket shelves. But there is every indication that they

are a minority, albeit one that is vocally represented by a few female brothel

owners and prostitution lobbyists like Felicitas Schirow.

German

law takes a fundamentally erroneous approach, says law professor Gugel. To

protect women, she explains, prostitution needs to be limited and the customers

punished. Hers is a lone voice in Germany.

But

not elsewhere in Europe. Some countries that once pursued a path similar to

Germany's are turning away and following the example set by the Swedes. Two

years before Germany passed its prostitution law, the Swedes took the opposite

approach. Activist Kajsa Ekis Ekman is fighting to convince the rest of Europe

to emulate her country. Since publishing a book in which she described the

lives of prostitutes, Ekman has been traveling from one European city to the

next, as a sort of ambassador in the fight against human trafficking.

In

mid-April, Ekman's campaign took her to KOFRA, a women's center in Munich.

Ekman is blond, blue-eyed, petite and energetic. She sits on a narrow wooden

chair and is so intent on talking that the cup of coffee in front of her gets

cold -- as if there weren't enough time for all the arguments that are now

important to make.

As

a student in Barcelona, Ekman shared an apartment with a woman who worked as a

prostitute. She witnessed how pimps dominate their employees. "I've been

involved ever since I experienced how my roommate was selling her body,"

she says. Back in Sweden, she was astonished by a public debate over free love

and the self-determination of prostitutes. "What I had seen was

different," says Ekman.

Punishing the Clients, Not the Prostitutes

In

1999, when Sweden made it illegal to buy sexual services, its European

neighbors could hardly believe it. For the first time, it was the customers and

not the prostitutes who were being punished.

"Prostitution

now flourishes in obscurity," wrote the influential German newspaper Frankfurter

Allgemeine Zeitung, saying that it was a "defeat for the women's

movement in Sweden," and speculating that "dogmatic feminism" was

at work. Can a society that wants to be free of prudery punish men who visit

prostitutes? It can, says Ekman, citing the successes in her country, where

fewer and fewer men are paying for sex and where those who do are more and more

ashamed of it. "Before our law came into effect, one in eight men in

Sweden had visited a prostitute," she says, and notes that that number has

since declined to one in 12.

Of

course, prostitution still exists in Sweden, but street prostitution has

declined by half. The total number of prostitutes has dropped from an estimated

2,500 to about 1,000 to 1,500. Pimps bring women from Eastern Europe into the

country in minivans and they often camp out on the outskirts of cities, but

prostitution is no longer a big business. Critics counter that prostitution in

apartments and via the Internet has increased, and some men are now going to

brothels in the Baltic countries or Eastern Europe instead.

The

Swedish law isn't based on the prostitute's right to make autonomous decisions,

but on the equal status of men and women, which is enshrined in both the

Swedish and German constitutions. The argument, in greatly simplified terms, is

that prostitution is exploitation, and that there is always an imbalance in

power. The fact that men can buy women for sex, the Swedes argue, cements a

perception of women that is detrimental to equal rights and all women.

'Pimp My Bordello'

Sweden

punishes the customers, pimps and human traffickers, not the prostitutes. This

approach is intended to stifle demand for sex for money and make the business

unprofitable for traffickers and exploiters. Two years ago, the Swedes

increased the maximum penalty for johns from six to 12 months in prison.

Although

the police are not always especially assiduous about pursuing punters, they

have arrested more than 3,700 men since 1999. In most cases, the men were only

forced to pay fines. There are also debates in Sweden over whether the

restrictive law is the right approach, but it enjoys considerable support among

the population. Ten years after the law was enacted, more than 70 percent of

Swedes said they supported punishing the men who pay for sex instead of the

prostitutes they pay.

In

Germany, on the other hand, the situation is such that the RTL II television

channel broadcasts a show in which a "Pimp my bordello" team drives

around the country to visit "German brothels in trouble" and boost

the sex business with good advice. It is efforts like this that prompted Alice

Schwarzer, publisher of the feminist journal EMMA, to envision, "as

a near-term goal" for Germany, "a social debate that culminates in

the condemnation of prostitution instead of, as is the case today, its

acceptance and even promotion."

Pierrette

Pape believes that there are consequences to the way prostitution is viewed in

various countries. "Nowadays, a little boy in Sweden grows up with the

fact that buying sex is a crime. A little boy in the Netherlands grows up with

the knowledge that women sit in display windows and can be ordered like

mass-produced goods." Pape is the spokeswoman of the European Women's

Lobby in Brussels, an umbrella group for 2,000 European women's organizations.

Pape

finds it "surprising" that Germany is not seriously reviewing its

policies related to human trafficking. "The debate has begun throughout

Europe, and we hope that German politicians and aid organizations will pay more

attention to human rights in the future than they have until now."

Several

European countries now follow the Swedish model. In Iceland, which has adopted

similar legislation, politicians are even considering a ban on online

pornography. Since 2009, Norway has also punished the customers of prostitutes.

In Barcelona, it is illegal to employ the services of a street prostitute.

The French Approach

Under

a Finnish law enacted in 2006, men can be punished if they were customers of a

prostitute who works for a pimp or is a victim of human trafficking. But it has

proved to be impossible to prove that the men knew that this was the case. The

Finnish Justice Ministry is now preparing a report on whether Finland should

adopt the Swedish model.

Many

in France also want to emulate Sweden. Shortly before taking office, the

minister responsible for women's rights, Najat Vallaud-Belkacem, made a bold

announcement. "My goal is to see prostitution disappear," she said.

Politicians and sociologists derided the idea as "utopian," and

prostitutes protested in the streets of Lyon and Paris. Vallaud-Belkacem's

draft law calls for up to six months in prison and a €3,000 fine for clients.

But it will probably take some time before she can prevail within the

government.

And

in Germany? Politicians in Berlin argue over minimal changes to the

prostitution law and then end up doing nothing. In 2007, then-Family Minister

Ursula von der Leyen, a member of Chancellor Angela Merkel's Christian

Democratic Union (CDU), wanted to make brothels subject to government approval,

and fellow CDU member Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, who was interior minister of

the state of Saarland at the time (and who is now governor of the state),

supported her. But the two politicians failed to secure a majority within their

party and nothing happened.

In

2008, the Conference of Equality and Women's Ministers tried to introduce a

rule that would make brothel operators subject to a reliability test. They

consulted with their colleagues in the Conference of Interior Ministers, but

nothing happened.

Standing Pat

In 2009, female

politicians from the CDU, the SDP, the business-friendly Free Democratic Party

(FDP) and the Green Party in the southwestern state of Baden-Württemberg called

for an initiative in the Bundesrat, the legislative body that represents the

German states, against "inhuman flat-rate services." But no changes

were made to the law.

The

Netherlands chose the path of legal deregulation two years before Germany. Both

the Dutch justice minister and the police concede that there have been no

palpable improvements for prostitutes since then. They are generally in poorer

health than before, and increasing numbers are addicted to drugs. The police

estimate that 50 to 90 percent of prostitutes do not practice the profession

voluntarily.

Social

Democrat Lodewijk Asscher believes that the legalization of prostitution was

"a national mistake." The Dutch government now plans to tighten the

law to combat a rise in human trafficking and forced prostitution.

The

Germans aren't there yet. The Greens, who played such an instrumental role by

supporting the prostitution law 12 years ago, have no regrets. A spokesperson

for Kerstin Müller, the Green Party parliamentary floor leader at the time,

says that she focuses on other issues today. Irmingard Schewe-Gerigk, who was

also a leading Green Party parliamentarian at the time the law was passed,

says: "The law was good. It's just that we should have implemented it more

thoroughly." Interestingly enough, Schewe-Gerigk is now the chairman of

the women's rights organization Terre des Femmes, which aims to achieve "a

society without prostitution."

The

third pioneer of the new law at the time, Volker Beck, also continues to

support it today. Beck, his party's former legal policy spokesman, does call

for new assistance programs and exit programs. But he says that Sweden cannot

be a model for Germany. "A ban doesn't improve anything, because then it

will just happen in places that are difficult to monitor," Beck says.

Besides, he adds, "criminal gangs will take over the business" -- as

if upstanding businesspeople were the ones running it today.

'Realm of Illegality'

A

few of his fellow Greens disagree. "A large segment of the industry is

already operating in the realm of illegality today," says Thekla Walker

from Stuttgart. The chair of her party's state organization, Walker has sought

to change her party's approach to prostitution.

"The

autonomous prostitute we envisioned when the prostitution law was enacted in

2001, who negotiates on equal terms with her client and can support herself

with her income, is the exception," reads a motion Walker introduced

during a party convention last month. The current laws, it continues, do not

protect women from exploitation, but grants them "merely the freedom to

allow themselves to be exploited." The Greens, Walker wrote, cannot turn a

blind eye to the "catastrophic living and working conditions of many

prostitutes."

But

they did. Walker withdrew the motion because it stood no chance of securing a

majority, though the party has said it would take a closer look to see if the

law requires improvements.

In

Germany, those who speak out against legalization are considered "prudish

and moralizing," says law professor Gugel. Besides, she adds, she doesn't

have the feeling "that politicians have much interest in the

subject."

Family

Minister Kristina Schröder, though, did in fact set out to crack down on human

trafficking and forced prostitution. "Despite very intensive efforts, it

hasn't been possible to achieve unanimity among the four ministries

involved," Schröder's ministry said in a statement. Her desire to regulate

brothels more heavily failed in the face of opposition by Justice Minister

Sabine Leutheusser-Schnarrenberger. Schnarrenberger believes that reforming the

law is unnecessary and repeats the old argument, namely that the German law

brings women out of illegality while the Swedish law forces them into the dark.

Given

such disagreement, it would be a miracle if the government reached a decision

soon to protect victims of human trafficking more effectively. Instead, women

will continue to have to fend for themselves.

Completely Legal

Alina

from Sânandrei managed to flee from the Airport Muschis brothel. After a raid,

she and 10 other women ran to a Turkish restaurant in the neighborhood. The

owner's brother, who was a customer, hid the women and rented a bus at his own

expense. Then he tried to drive them to Romania. The pimps tried to stop the

bus, but the women were able to escape.

Alina

now lives in her parent's house again. She hasn't told them about what

happened. She is working, but she doesn't want to say what she does. The pay,

she says, is enough for her bus ticket, clothes and a little makeup.

Alina

sometimes visits the AIDrom, a counseling center for victims of human

trafficking in the western Romanian city of Timisoara, where she speaks with

psychologist Georgiana Palcu, who is trying to find her a training position as

a hairdresser or a cook. Palcu says that the conversations with young women who

have returned from Germany are "endless and difficult." She

encourages them to be optimistic.

But

Palcu has no illusions. Even if a girl could find a training position, she

probably wouldn't take the job, because such positions offer no more than €200

for a 40-hour workweek. As a result, says Palcu, many of those who returned

from Germany after being mistreated there are working as prostitutes again.

"What can I tell them?" she asks. "This is reality. You can't

live on €200."

The

Airport Muschis brothel in Schönefeld no longer exists. It's been replaced by

Club Erotica, which does not offer flat-rates. But johns still have plenty of

choice in the area. A few kilometers away in Schöneberg, the King George has

switched to flat-rate pricing..... For €99, clients can enjoy sex and drinks

until the establishment closes.