We all know the gloomy statistics: some 49 percent of

Fortune 1000 companies have one or no women on their top teams. The same is true

for 45 percent of boards. Yet our latest research provides cause for optimism,

both about the clarity of the solution and the ability of just about every

company to act.

Almost two years ago, when we

last wrote in McKinsey Quarterly about the

obstacles facing women on the way to the C-suite, we said our ideas for making

progress were “directional, not definitive.”1

Since

then, we’ve collaborated with McKinsey colleagues to build a global fact base

about the gender-diversity practices of major companies, as well as the

composition of boards, executive committees, and talent pipelines.2

We’ve

also identified and conducted interviews with senior executives at 12 companies

that met exacting criteria for the percentage of entry-level female

professionals, the odds of women advancing from manager to director and vice

president, the representation of women on the senior-executive committee, and

the percentage of senior female executives holding line positions.3

And in a separate research

effort, we investigated another group of companies, which met our criteria for

the percentage of women on top teams and on boards

of directors—a screen we had not used for the first 12 companies

identified.4

All told, we interviewed

senior leaders (often CEOs, human-resource heads, and high-performing female

executives) at 22 US companies. Two emerged as high performers by both sets of

criteria.5

This

article presents the interviewees’ up-close-and-personal insights.

Encouragingly, many of the themes identified in our research over the years—for

example, the importance of having company leaders take a stand on gender

diversity, the impact of corporate culture, and the value of systematic talent-management

processes—loom large for these companies. This continuity is reassuring: it’s

becoming crystal clear what the most important priorities are for companies and

leaders committed to gender-diversity progress. Here’s how the top performers

do it.

1.

Diversity is personal

CEOs and senior executives of our top companies

walk, talk, run, and shout about gender diversity. Their passion goes well

beyond logic and economics; it’s emotional. Their stories recall their family

upbringing and personal belief systems, as well as occasions when they observed

or personally felt discrimination. In short, they fervently believe in the

business benefits of a caring environment where talent can rise. “I came here

with two suitcases, $20 in my pocket, and enough money for two years of

school,” one executive told us. “I know what kind of opportunities this country

can provide. But I also know you have to work at it. I was an underdog who had

to work hard. So, yes, I always look out for the underdogs.” Similarly, Magellan

Health executive chairman René Lerer’s commitment stems from watching his

parents struggle. “Everyone is a product of their own experiences and their own

upbringing,” Lerer said. “The one thing [my parents] strived for was to be

respected; it was not always something they could achieve.”

Of course, CEOs cannot single-handedly change the

face of gender diversity: the top team, the HR function, and leaders down to

the front line have to engage fully. But the CEO is the primary role model and

must stay involved. “It has to start at the top, and we must set expectations

for our leaders and the rest of the company,” Time Warner Cable chairman and

CEO Glenn Britt said. “I’ve cared about this since the beginning of my career.

I wasn’t CEO then, of course, but it was important to me and has continued to

be.” Leaders of top performers make their commitment visible as well as verbal:

Kelly Services CEO Carl Camden heads the company’s Talent Deployment Forum and

personally sponsors women and men within the organization. “You can say all you

want about the statistics, but an occasional act that’s highly visible of a

nontraditional placement of somebody that advances diversity also is a really

good thing,” Camden said. “It gets more talk than the quantity of action would

normally justify.”

The bottom line:

Numbers matter, but belief makes the case powerful. Real stories relayed by the

CEO and other top leaders—backed by tangible action—can build an organizational

commitment to everything from creating an even playing field to focusing on top

talent to treating everyone with respect. Each time a story is told, the case

for diversity gets stronger and more people commit to it.

2.

Culture and values are at the core

For many of our best-performing companies, a culture

of successfully advancing women dates back decades. “In 1926, we hired our

first woman officer,” Aetna CEO Mark Bertolini said. “She was the first woman

allowed to walk through the front doors of the building—which paved the way for

all women who came after her. That kind of groundbreaking courage early in our

history created the mobility inside the organization necessary for the many

women at Aetna succeeding today.”

Companies such as Adobe and Steelcase also have long

histories of commitment to inclusion. “I am a big believer that so much of it

is role modeling,” Adobe CEO Shantanu Narayen said. “If you have good role

models, then people are inspired.” And at Steelcase, long known for its focus

on people, CEO Jim Hackett speaks with passion about being “human centered”—essentially,

creating the kind of flexible, nurturing environment in which all people

thrive. Interestingly, while these companies perform well on gender-diversity

measures, they don’t do so by focusing on

women. Instead, they have changed the way employees interact and work with one

another, a shift that benefits women and men alike.

The bottom line:

Gender-diversity programs aren’t enough. While they can provide an initial

jolt, all too often enthusiasm wanes and old habits resurface. Values last if

they are lived every day by the leadership on down. If gender diversity fits

with that value set, almost all the people in an organization will want to

bring more of themselves to work every day.

3.

Improvements are systematic

Achieving a culture that embraces gender diversity

requires a multiyear transformation. Strong performers maintain focus during

the journey, with the support of an HR function that is an empowered force for

change. Such a culture manifests itself primarily in three areas that work to

advance women: talent development, succession planning, and measuring results

to reinforce progress. Campbell’s, for example, develops women by providing

special training for high-performing, high-potential talent, as well as

opportunities to interact with CEO Denise Morrison and board members. Carlson

seeks to develop female leaders through job rotations in functional and line

roles. Current CEO Trudy Rautio, for example, previously served as the

company’s CFO and as the president of Carlson Rezidor Hotel Group’s North and

South American business.

It’s critical to identify talented women and look

for the best career paths to accelerate their growth and impact. Many companies

convince themselves that they are making gender-diversity progress by creating

succession-planning lists that all too often name a few female “usual

suspects,” whose real chances for promotion to the top are remote. In contrast,

the aforementioned CEO-led Talent Deployment Forum at Kelly Services discusses unusual suspects for each role, finding surprising

matches to accelerate an individual’s development and, sometimes, to stimulate

shifts in the company’s direction. (For one female leader’s surprising story in

another organization, see sidebar, “‘They were just shocked that I wanted to

go.’”) And sponsorship is an expected norm, from the CEO on down the line,

which becomes self-perpetuating: at companies such as MetLife, we found that

when women make it to the top, they provide ladders for others to climb.

Sidebar

‘They were just shocked that I wanted to go’

Wall Street Journal deputy editor in chief Rebecca

Blumenstein reflects on her posting to China.

I had no plan to go to China, but one day they sent

a note out because they didn’t know who the next bureau chief was going to be.

I looked at that note and thought, “I’ve been hearing about China forever. I’ve

wanted to work there. But now I’m stuck. I have a house in the suburbs and

three kids.” So I didn’t mention it to my husband.

Very randomly, that weekend we were at the pizza parlor

after a soccer game. I was talking to a mom who was a talent scout at NBC. She

asked, “How big is the Journal? How many

reporters do you have around the world?” And I said, “Oh, you know, we have X

reporters around the world, Y bureaus around the world; we’re even looking for

someone to run China right now.” Alan, my husband, said, “China? I’d go to

China.” So this is how my career development went! Alan said, “The Olympics are

coming, and I do music and sports, and this is a great time. China’s one of the

only places where I could really get a lot of work.” We talked to his aunt, a

school psychologist, who said, “If you’re ever going to move, you should move

now because your kids are young,” which was totally right. And so I sent a note

to my editors on Monday. They were just shocked that I wanted to go. It was a

competitive process. I remember coming home at one point and saying, “Are you

sure you want to do this? Because the train is leaving the station—if I am

offered, we’d better do it.”

I got an offer and we took a trip just to make sure

this wasn’t a huge mistake. I don’t mean to downplay how scary it was. It was a

big deal. It was polluted, and there were some challenges. We went to a park

and took pictures of fun things, like a big ball pit called Fun Dazzle, a

swimming pool filled with balls. It was the biggest thing that I’d ever seen.

We came home and called the kids out to the front lawn and said, “We’ve been to

China. We’re going to move there; here are some pictures.” My oldest son, I still

remember to this day, said, “This looks great! I want to go to China.”

This is a period of such potential for women. It’s

inspiring to look at how well women are doing at all levels of education. The

world is open to us. I think it’s important not to tell women what they can’t

do but to tell women what they can do. Society has told women that if you work,

you’re a bad mom. That’s pretty much the message: if you’re a committed mom,

you’re not trying to do it all. Instead of beating ourselves up, it would be

good to be someone who can tell people that it is possible to have a fulfilled,

complete life and be challenged.

It’s much more accepted in other countries for women

to work and to be moms, and we’re still really struggling in America. I think

we have all these tough, talented girls playing soccer and going to college. We

need them to be leaders of this country. The US is facing a much more uncertain

future than it has; spending time in Asia puts that firmly into perspective. If

we’re not tapping our women in America, then we’re limping with one good foot

and one that’s trailing behind. We’re going to need both of them. We’re going

to need everybody.

I have many friends who don’t work. Some of the most

impressive women I know don’t work, and I deeply respect that choice. But as

their kids get older, I’ve noticed more of them ask, “What happened to me? What

should I do?” I’ve turned from a subject of some scorn because of my work (“Oh,

I’m away too much”) to something some people are almost jealous of. I do have

angst about time with my kids. My freshman son in high school has papers all

over the place, and I wish that I were there more to be all over him and ask,

“What are you doing? You need to be on top of this!” But time is moving so

fast; I do appreciate my kids and love spending time with them, as they are

growing up so quickly. Still, when they’re older, I think that I’ll be glad I

stuck with it.

About the authors

Rebecca Blumenstein,

deputy editor in chief of the Wall Street Journal,

has served since 2011 as a host of the paper’s Women in the Economy conference,

for which McKinsey is the research partner. From 2005 to 2008, she was the

publication’s bureau chief in China. Blumenstein offered these reflections

during an interview with Joanna Barsh,

a director emeritus in McKinsey’s New York office.

Another Fortune 50 company ties gender diversity to

talent planning and compensation in order to drive results. “When you have a

succession plan and are looking at current and future openings, you need to be

intentional about how to place women in those roles,” an executive at the

company said. “When there is no woman to fill a gap, you need to ask why and

hold someone accountable for addressing it. We tie it to the performance-review

process. You may be dinged in compensation for not performing on those

dimensions.” Ernst & Young goes even further: it compares representation

for different tenures of women in “power” roles on its biggest accounts with

overall female representation for comparable tenure levels and geographies.

When those two metrics are out of sync, E&Y acts.

The bottom line:

Get moving. Evidence abounds about what works for identifying high-potential

women, creating career opportunities for them, reinforcing those opportunities

through senior sponsorship, and measuring and managing results.

4.

Boards spark movement

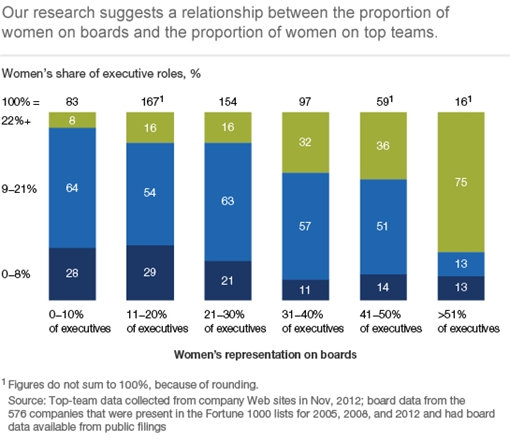

Our research suggests a correlation between the

representation of women on boards and on top-executive teams (exhibit). Leaders

at many companies encourage female (and male) board members to establish

relationships with potential future women leaders and to serve as their role

models or sponsors. And it was clear from our interviews that the boards of the

best-performing companies provide much-needed discipline to sustain progress on

gender diversity, often simply by asking, “Where are the women?” “The board

oversees diversity through the HR and the governance and nominating

committees,” Wells Fargo CFO Tim Sloan said. “They ask the right questions on

leadership development, succession planning, diversity statistics, and policies

and procedures, to make sure the executives are following up. Our board members

tend to be very focused on these topics. While I don’t think our diverse board

is the main driver of our diversity, if we had no female board members it would

send the wrong message.”

Working in tandem with HR professionals, the boards

of leading companies dig deep into their employee ranks to identify future

female leaders and discuss the best paths to develop their careers. Dialogue

between the board and top team is critical. “The board asks us what we’re doing

to increase diversity, and we report [on] diversity to the board regularly,”

said Charles Schwab senior vice president of talent management Mary Coughlin.

Most boards of Fortune 1000 companies have too few

women to be engines for change: we found that it would take an additional 1,400

women for all of these boards to have at least three female members. Of course,

nominating and governance committees wedded to the idea of looking only for

C-suite candidates will all be knocking at the same doors. If companies cast a broader

net and implement age and term limits to encourage rotation, they will have

plenty of talented, experienced women to choose from. In fact, we estimate that

2,000 women sit on top teams today—not counting retirees and women in

professional-services or private companies.

The bottom line:

Women on boards are a real advantage: companies committed to jump-starting

gender diversity or accelerating progress in achieving it should place a

priority on finding qualified female directors. It may be necessary to take

action to free up spots or to expand the board’s size for a period of time.

The data we’ve analyzed and the inspired leaders

we’ve met reinforce our confidence that more rapid progress in advancing women

to the top is within reach. Frankly, the formula for success should no longer

be in doubt. And though following it does require a serious commitment, if

you’re wondering about what legacy to build, this one is worthy of your

consideration.

About the authors

Joanna Barsh is a director emeritus in McKinsey’s New York office, where Sandra Nudelman is an associate principal; Lareina Yee is a principal in the San Francisco office.