WUNRN

All-China Women's Federation

CHINA - LEFT-BEHIND RURAL WOMEN WITH

HUSBANDS WORKING IN CITIES

|

December 11, 2012 |

By Ye Jingzhong, ZhiChunli and Su Yi |

Editor: Sun Xi |

|

|

|

|

Many rural Chinese women are left to shoulder the burden of domestic duties after their husbands leave to find jobs in the cities. [news.qq.com]

|

A research report conducted by the Research Group for

China's Rural Left-behind Women's Studies under China Agricultural University

reveals that China has nearly 50 million left-behind women for whom high labor

intensity, heavy psychological burdens, and life stress weigh as heavily as

'three big mountains' on their shoulders.

Left-behind women are women whose husbands have left their rural hometowns to

seek better-paying jobs in the cities.

One scholar, who has been studying the Chinese left-behind population for

years, believes that the large number of these women, as well as the heavy

burdens they bear, are not only unique in the history of China, but also in the

modernization process of the world.

While the plight of left-behind children and the elderly receive considerable

media attention, these women are often overlooked by society. Many of them

worked alongside their husbands in the cities, but were forced to return to the

rural countryside to raise their children. For these women, life is lonely and

harsh.

A Village without Husbands

"We had been married for only a few months when he went abroad to work. I

missed him very much at first. But now, I've gotten used to it," said

Zhang Juan, a villager from Wujiawan Village, Huangbei District in Wuhan City,

capital of central China's Hubei Province.

"The hardest thing is doing the heavy physical work on my own, like

changing the gas tank. And the thing that I worry about the most is my child's

safety. The kindergarten has a minibus to pick up the kids, but I often hear

about local bus accidents. Even if I send him to school by motorcycle, it is

still unsafe," Zhang said.

But what is even more unbearable than the heavy housework is the psychological

torment. Zhang Juan has a friend called Shen Li, whose husband used to work in

Libya. In early 2011, she watched the mounting tensions in Libya and was

overwhelmed with worry for her husband's safety.

"I couldn't get in touch with him on the phone or through the Internet. I

was worried to death. Thank God he finally came back after half a month. Since

then, I have not allowed him to work abroad," Shen said.

The young husbands of Wujiawan only return home once a year, for the

traditional Spring Festival reunion. Shen takes care of her two children on her

own, as her husband works in another Chinese city now. "At first, I was

very afraid and used to close all the doors and windows at night. But I slowly

got used to it."

In fact, many of these women used to work alongside their husbands in the

cities, but returned home to take care of their children. For them, aside from

domestic and child-minding duties, life is an endless round of TV programs and

games of mahjong with neighbors.

"I want to go out to work too. But the town is too far away and it would

make it very inconvenient to take care of my child," said Zhang.

Neither Here nor There

Peng Huiling, who just moved back to her rural hometown this Spring Festival,

feels like a fish out of water in the rural surroundings she came from.

Originally from a village in Wuhan, she and her husband had been working in

Xiamen in southeast China's Fujian Province. She was a supermarket saleswoman

and her husband worked as a carpenter.

"Xiamen is really great. I liked the weather, the scenery, and the whole

environment there. I had a lot of friends there as well. Life back in my

hometown is so boring," said Peng, who clearly misses her life in the

city. "But for my child's sake, I have to move back here and leave my

husband to earn our living in the city alone."

Peng's daughter is five years old and will soon be in elementary school.

"We let her grandparents take care of her in the past, but they spoiled

her and she was very badly behaved. I had to return to take care of her myself.

I hope that her life will be better than ours and that she can leave these

rural surroundings."

Peng's greatest wish is for the three of them to live together in Xiamen. Last

year, they tried bringing their daughter with them to the city. "She was

very happy. But it took us only two months to realize that we can't afford to

raise a child in the city. My daughter sensed the situation and asked to go

back to the countryside," Peng said.

"She didn't want to leave us. Every year when we returned to the city

after the Spring Festival holidays, she would cry and cry," Peng said.

Peng's stint in the city has also given her a new perspective on rural life. In

her opinion, the children in the village suffer from a lack of after-school

activities. She compares them to children in the cities, who often attend extra

classes or extracurricular activities after school.

She also says that she is unsure about her parenting practices, but does not

know where to turn to for guidance. "I used to attend lectures on how to

raise children when I was living in Xiamen. But there are no lectures here and

I have forgotten all the things I learned," she says, plaintively.

Long-distance

Loneliness

Some

left-behind women in their 50s have been living alone for over 20 years. Peng

Fenglan, deputy director of the village committee of a village in Wuhan, is one

of them.

Peng used to work in the city with her husband, but when her daughter was

injured from a fall as a toddler, she was forced to move back to take care of

her. From the age of 4 to 19, her daughter underwent four surgeries to treat

her injury, costing the family 100,000 yuan (US$ 16,050). Their daughter is now

in college.

To raise the money for their two children's tuition fees, her daughter's

medical expenses, and their parents' allowance, Peng and her husband have lived

apart for years.

"I work in the fields during the day and work for the village committee at

night during the busy season. Without modern-day farming tools and the rural

senior citizen pension, I have no idea how we would have gotten through the

hard times. When my children graduate from college and my husband cannot work

anymore, he will return and we will have our twilight years together in the

village," she said.

Peng's wistful hope of spending her elderly years with her husband is one that

many of the women share. Although each of them has a different story, they all

dream of the day they will be reunited with their husbands.

Zhang Juan hopes that when they save enough money, her husband can return to

her and they will open a small clothing store in the town. Peng Huiling hopes

she can set up a fish breeding or poultry raising business while taking care of

her child, so she and her husband will gain a foothold in the city in the

future.

Hard Lives of Rural Wives

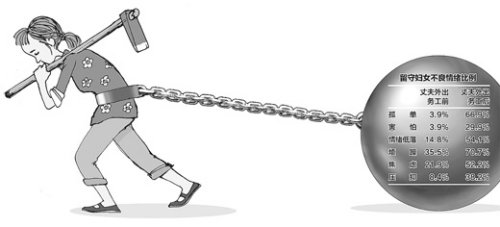

Aside from loneliness, these women are also vulnerable to marital and

psychological problems.

According to recent research, nearly 54 percent of these long-distance

marriages are failing, and 81.6 percent of the women believe that having

husbands who work so far away has negatively impacted their family and marriage

due to the long periods of separation and lack of communication.

In addition, differences in environment eventually take a toll on these

marriages, with the relatively urbanized husbands sometimes looking down on

their rural wives and deeming them old fashioned or outdated.

According to data from the Ministry of Health, about 80 percent of migrant

workers are sex deprived. Many of the left-behind women are in the same state

as well, and are also more vulnerable to becoming targets of sexual harassment.

As a result, extramarital affairs and divorces are common among these

long-distance marriages. According to the Civil Affairs Department, rural

divorces caused by one spouse working away from home accounted for as much as

60 percent or more.

Getting divorced can have cataclysmic consequences for these women who often

rely on their husbands for living and emotional support. Once divorced, these

women undergo significant psychological trauma.

"Their lives are all about their children, elderly parents and farm work.

All the issues that confront them in life do not have an outlet for

release," said associate psychology professor Zhang Wanying from the

Qingyuan Polytechnic. "They are lonely."

Solutions Needed

If not handled properly, the problems confronting these left-behind women will

inevitably affect the well-being and stability of China's rural areas.

A survey conducted by the China Agricultural University in 2008 shows that

there are 87 million rural left-behind people, including 20 million children,

20 million senior citizens and 47 million women.

Although left-behind women account for half of this group, the burdens they

bear are often overlooked when compared to those of the children or senior

citizens.

A survey published in 2008 by the Research Group for China's Rural Left-behind

Women's Studies under the China Agricultural University, shows that 63.2

percent of these women often feel lonely, 42.1 percent of them often or

sometimes cry, 69.8 percent feel agitated all the time, 50.6 percent often feel

anxious, and 39 percent often feel depressed.

"My husband and I have been married for 14 years, but we have lived

together for less than a year," said one frustrated left-behind woman.

For them, the basic benefits of having a spouse which most other women take for

granted, such as having a life companion, parenting partner and emotional

pillar to lean on, are missing.

"As long as the social development pattern of urbanization and

industrialization doesn't change, the rural left-behind women's issues will

exist," stated the research report conducted by the Research Group for

China's Rural Left-behind Women's Studies. "Governments at the grassroots

level should maintain a normal social order to free women from their worries.

For instance, they can reduce the farm work burden on these women by improving

irrigation and water conservancy facilities. They also need to ensure that

these women's land rights are upheld in terms of land use compensation."

The report goes on to state the importance of society's role in easing the

lives of these women through institutional arrangements. It recommends

communications subsidies and vacation benefits for migrant workers to encourage

them to visit home more often.

The good news is that as the urbanization process speeds up, more and more

factories are being built near rural areas, providing employment for the women

and making it unnecessary for their husbands to find jobs elsewhere.

"The newly-constructed industrial park around our village provides us with

a lot of opportunities. My husband has now opened a small business near it and

I also found a job there. Our lives are much better now," said one

50-year-old woman, Wang Qiaozhen from Xinchun Village in Wuhan.

Although there are still a lot of other challenges to take on before the plight

of China's left-behind women is fully resolved, this is a heartening start.