WUNRN

Women News Network - WNN

FILM SHOWS SECRET TRAGEDY OF

"HONOUR" BASED VIOLENCE/FEMICIDE

FILM TRAILER SEGMENT: http://fuuse-films.com/ - Click Arrow to Start.

Also featured on page 2 at end of

WNN article.

A

blurred still image taken during a

(WNN) London, UNITED KINGDOM: The Honour Based Violence Awareness Network says today the UNFPA – United Nations Population Fund statistics estimates that 5,000 “so-called honour” killings are committed around the world every year. Across the Western world there are rising levels of ‘honour’ violence. This form of crime is distinguished from others by its collaborative and highly ritualized nature, typically involving members of the victim’s immediate family.

This kind of per-meditated violence inside a family may be unbelievable. But it continues to happen worldwide. and many of its victims belong to migrant families

A ground-breaking new film documentary, “Banaz: A Love Story,” produced by the prize winning human rights activist and critically acclaimed woman singer and composer from Norway known throughout the music world as Deeyah, includes a searing ‘inside look’ into the life of Banaz Mahmod who tried over and over again to get protection from the London police before her untimely death in an ‘honour’ killing. It includes never-before seen footage recorded by Banaz’s boyfriend Rahmat. The film also includes interviews with Banaz’s sister Bekhal, and an up-close look at the Scotland Yard detective, Chief Inspector Caroline Goode, who worked tirelessly to track down the killers of Banaz.

Today both Rahmat and Bekhal are hiding separately in undisclosed locations

in

“Honour Killing is not really a crime of passion. It’s pre-meditated,” said Deeyah to London based human rights activist, publisher and founder Chris Crowstaff of The Safe World International Foundation in a 2006 interview as Deeyah was in the early stages of the film’s production. “And it’s not the crime of just one person. It’s typically planned by a number of people, and not something that happens in the heat of a moment of passion or insanity between one person unleashing violence against another,” continued Deeyah.

In 2006

Although many people don’t know this, murder is only one of many other kinds

of ‘honour’ crime. Other types include forced abortion, female genital

mutilation known as ‘hymen repair’ by those families who inflice this on their

daughters, abduction or forced marriage, forced prostitution, and lastly

‘honour suicide.’ According to Diana Nammi, the director of the IKWRO – Iranian

and Kurdish Women’s Rights Organisation in

Including raw footage from the

In the footage from one of her visits to the police Banaz sits calmly in a red sweater, a glimpse of a delicate gold necklace peeks out from beneath her collar. She carefully describes abuse, a forced marriage, stalkers and threats against her life made by her own relatives. “When he raped me it was like I was his shoe that he could wear whenever he wanted to. I didn’t know if this was normal in my culture, or here. I was 17.” Banaz said describing the husband her family had chosen for her. When she finally left her husband, she said her family was furious with her.

“Now I have given my statement. What can you do for me?” she asked the police officer in attendance once the details of her story had been made ‘on-the-record.’ A chilling silence follows her question as the officer recording Banaz’s statements offers her no refuge.

For a moment, Banaz’s head hangs heavy. Before her statement to the police

had been made, her sister Bekhal had also already been threatened by her

family. Because of this Bekhal was now living in hiding, “If she was still

alive,” said Banaz to the police. Her sister was estranged not only from her

parents but from the entire community. Sitting at the police station in

Shockingly this was the first of many statements Banaz would make to the police before her death.

Banaz Mamod’s nickname was a Kurdish word that means tenderness, the softness of a new born lamb, that matches the soft voice of Banaz as she tells her story of abuse and fear at the hands of her tormentors. Exclusive first-time interviews in the film with Banaz’s sister Bekhal, who wears a black veil covering her face to protect her from retaliations, introduces us to Banaz through childhood memories.

Bekhal also shares her own memories as her family attempted to commit ‘honour’ crimes against her: forcibly circumcising her with a knife when she was a teenager, then later beating her and trying to kill her. She also describes how today she continues to live with what she calls an “omnipresent fear.” Her dark eyes swell with tears; “My only regret is I should have taken Banaz with me [when I fled],” she says.

In the making of Deeyah’s film, no friends or other family members would speak on camera about Banaz – even her boyfriend Rahmat, who contributed short videos of Banaz in the hospital and text message conversations to the film production. No one who knew Banaz when she was alive would speak about her to the production crew.

All of the film’s other interviews are from activists and law enforcement. All learned about the fate of Banaz after her death. The documentary features conversations with Detective Chief Inspector Caroline Goode, who won the Queen’s Award in 2011 for her dedicated efforts in tracing and jailing Banaz’s murderers.

The publicity that surrounded this case, years after Banaz’s murder, brought

harsh criticism against the British police, and a new awareness about ‘honour’

crime in

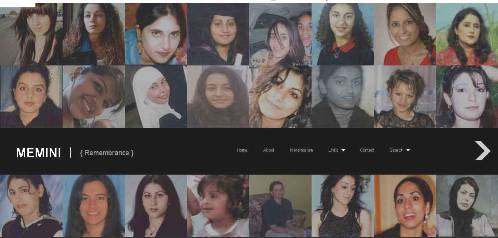

Memini

is an online project that was created by rights activist filmmaker, musician

and celebrity Deeyah in 2011. It chronicles and gives dignity to the victims of

‘honour’ violence who now unable to speak for themselves. Banaz Mahmoud is only

one of many of the faces included in this online memorial. Image: Deeyah

After the recent October 1, 2012 premier of the film at the Raindance Film Festival in

Deeyah’s film concludes with pictures of young British women who come from

immigrant families, the names and photographs of dozens who have been murdered

in ‘honour’ killings by their fathers, brothers, cousins, uncles and husbands.

Most of these murders are still unsolved. In the

So how can we stop the on-surge of ‘honour’ violence worldwide?

There are many challenges for those who are now working to stop the ‘honour’ killings. One major obstacle is the lack of education, training and/or networks within law enforcement that address the issues facing young women trapped by abuse and family hierarchies.

An attorney working for a United States based women’s shelter in Texas recently told CBS news about two U.S. cases: a stepmother trying to protect a child from mutilation and a 16-year old runaway whose parents were threatening to sue the shelter where she found refuge if it allowed her to remain there. International advocates working to stop the violence agree: Law enforcement needs education to help them recognize and identify these potential crimes. They also need to find resources to care for a victims who can’t return home.

Governments too have failed to protect their citizens from ‘honour’ crimes,

either through official laws or the unwritten, common practice of denial say

the advocates. Sometimes it is a deadly combination of the two. In 2011

international human rights monitor Human Rights Watch reported that the

current Iraqi law “limits the prison sentence to less than three years for an

honor killing of a wife by her husband.” It wasn’t until 2011 that Palestinian

Authority President Mahmoud Abbas finally declared ‘honour’ killings a crime in

the

In nations with clear laws against such violence, such as

As a human rights activist of mixed Pakistani and Afghan descent, Deeyah does not accept such concerns as a valid excuse. “We shall not sacrifice the lives of ethnic minority women for the sake of so-called political correctness,” she outlined. “I’d rather hurt feelings than see women die because of our fear, apathy and silence,” she added.

British stop ‘honour’ violence activists have also accused British police

officers of leaking information about a victim’s location to their

perpetrators. Greater overall accountability among law enforcement is essential

to resolving ‘honour’ crime around the world say the advocates. Although

efforts to bring greater awareness to the police force in

Another major hurdle is the lack of public awareness and the grave

misconception that ‘honour’ violence is committed only against women, not men,

who live in Muslim countries or in immigrant communities. According to Amtal

Rana, project worker at

‘Honour’ violence does not only affect those within a given community. In

August 2004, a gang of Muslim men in the

Other experts say that levels of ‘honour’ violence does not have any proven

correlation to a family’s economic situation, level of education or

‘integration.’ A 2008

report by a U.K. based CIVITAS

sponsored project called the Centre for Social Cohesion says, “This is not a

one-time problem of first-generation immigrants bringing practices from ‘back

home’ to the UK. Instead honour violence is now, to all intents and purposes,

an indigenous and self-perpetuating phenomenon which is carried out by third

and fourth generation immigrants who have been raised and educated in the

The control of women against their will is a basic tenant of ‘honour’ based

violence that lingers inside numerous communities today, the advocates agree.

“The Jewish experience shows even members of the most prosperous and

long-established immigrant groups in the

Religion, race, nationality and culture are not causes of ‘honour’ violence;

they are merely circumstances. ‘Honour’ based crimes are part of the landscape

inside the

These are just one of many other stories in the

The film documentary about Banaz Mamod is “a love story at its core,” says filmmaker Deeyah. Banaz’s sister Bekhal’s decision to come forward and speak about her sister, saturates the tale of violence with overwhelming love, bravery and strength.

Making the film has come with a dangerous price though. In the process of making the film Deeyah has received numerous threats for her work raising awareness about ‘honour’ violence. “That Banaz’s voice can finally be heard is far more important in the greater scheme of things than worrying about my safety,” says Deeyah. “Maybe in death we can give her the respect of finally listening,” she added.