WUNRN

Women News Network

Article page 2 website includes

video.

IRAN - IMPRISONED MOTHERS' GREATEST

FEAR IS BEING FORGOTTEN

Elahe

Amani with

Iranian human rights defender Narges Mohammadi and her children Kiani and Ali. Image: Narges Mohammadi

(WNN)

Imprisonment is not easy in

Worldwide the sentence for mothers in prison may, or may not, include their

children being allowed to stay with them while they are incarcerated. In the

In

In Cape Town, South Africa a new initiative to make mothers in prison and their children ‘child-friendly’ environments where children and mothers can be together in a natural and creative environment. The goal is to keep mother and child together and happy for at least two years.

With increasing women prisoners in Federal and State prisons, mothers are

often sent to detention facilities that are too far away for their families to

come visit them very often. Inside the

Iran human rights defender Narges Mohammadi

In the middle of the night on June 9, 2010, thirty-nine-year-0ld human

rights advocate Narges Mohammadi was taken away under arbitrary arrest by

A mother’s stress in prison can be overwhelming. “The rights of mothers and children to family life require special consideration,” says a handbook on good prison management by the International Centre for Prison Studies, which works with experts in human rights and prison reform. “Punishment [in prison] shall not include a total prohibition on family contact,” emphasizes the handbook. “In most societies women have primary responsibility for the family, particularly when there are children involved. This means that when a woman is sent to prison the consequences for the family which is left behind can be very significant,” added the report.

Mohammadi, as an incarcerated prisoner of conscience, was charged with

“assembly and collusion against national security” in

Today as a mother of twin children Narges is exceptionally vulnerable. So are her children.

Her son Ali, and his sister Kiani, are now six-years-old with a mother who

has been an active in

For her work as an advocate, in 2009 Narges was honored in Bolzano, Italy with an Alexander Langer award, but she was unable to attend the ceremony due to a ban placed against her against travel made outside of Iran.

In her place, Iranian Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Shirin Ebadi accepted

Narges’ award in

“If one day we realize the goals of Article 19 of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights, that will be a day of victory for human kind. If one day, humans can, without fear, insecurity, prison or death, express their beliefs and thoughts, and through peaceful means set out to publish those beliefs, authoritarianism will be undermined. But until that day, all those who hope for freedom will have a difficult road ahead,” added Narges in 2009.

In 2008, as a spokesperson and deputy head of

“I am a human being, a mother, a wife, how much more of this pain and suffering must I go through.”

–

Defenders of

The Defenders of Human Rights Center in

Narges Mohammadi’s sentence specifically mentions her “membership of the DHRC” as one of the ‘illegal charges’ that has put Narges in prison. A growing number of attorneys connected to the DHRC are also now in prison.

“…what hope is more powerful than the human chain across the world, where individuals from all corners of the world, act in solidarity to support one another,” said Mohammadi in response to her 2009 Alexander Langer award. “No longer can governments, with the excuse of national sovereignty, erect a wall around the peoples of their nations, and with the same excuse, treat their citizens as they please and view any voice of objection from around the world as an act of interference in their internal affairs.”

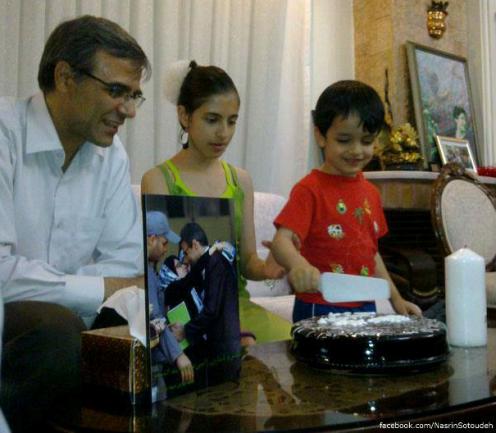

Celebrating her 12 year old birthday without her mother (incarcerated human rights attorney Nasrin Sotoudeh who is now serving a six year sentence) daughter Mahreveh and her brother Nima slice birthday cake with their father Reza Khandan. The family had prepared and hoped to celebrate Mahreveh's birthday with a visit to their mother in Evin prison, but the visitation was blocked by prison security. Image: Nasrin Sotoudeh Facebook

Members of the DHRC staff have faced excessive fines, harassment, intimidation and arbitrary detentions, as well as extended sentences in prison. Some have left the country to find asylum. Others, like human rights attorney and mother, Nasrin Sotoudeh, have been banned the Iranian justice system from working in their field as legal counsel for the next 20 years. Sotoudeh is also a mother. She is also currently living in Evin prison under a ‘difficult’ six year sentence which has included hunger strikes, sickness and interrogations.

Both Nasrin Sotoudeh and Nagres Mohammadi do not have proper access to their

children as women prisoners in

“I love you both very much. I wish you happiness and prosperity, like any other parent. I consider you first in every decision I make. One needs to consider the welfare of children in every decision. Receiving visits from you is very important to me. I suffer from not having held you for months. I am in pain from not hearing your voices,” Sotoudeh continued.

Marginalization of women prisoners

“The authorities in

We can try to talk to the mothers, but what happens to the children of women

prisoners in

“The legal rights of children under international law have been developing

since 1919, with both regional and global treaties safeguarding their

interests. Yet many of these rights, enshrined in the Convention on the Rights

of the Child and other texts, are put at risk when a parent is imprisoned,”

says the Quaker UNO – United Nations Office in

“One needs to consider the welfare of children in every decision.”

– Nasrin Sotoudeh,

incarcerated human rights attorney

Imprisonment worldwide most often includes limitations to human rights,

especially in

“My young children have been left with painful memories, memories and visions that affect them at night, in their dreams,” said Narges in an official letter of complaint made to government officials in Iran following an arrest of her husband, Taghi Rahmani, who was a Human Rights Watch Hellman-Hammet award winner in 1980.

Often prisoners of conscience are separated from family members as a tactic

of intimidation and breakdown. In April 2011 Iranian authorities “blocked

Narges Mohammadi from contacting her husband Taghi Rahmani in prison,” said the

International Campaign for Human Rights in

Today the children of Narges Mohammadi and Taghi Rahmani are without both

their mother and their father. Narges is now serving her full sentence. There

father and activist Taghi is currently living in asylum in

“I remember one night my children could not fall asleep, they were both speaking in their dreams… Earlier that night they had witnessed the security officers come to our home and scream obscenities and indignities on Taghi,” Mohammadi said. “I remember [my son] little Ali was walking around the house and muttered to himself…. Get out of my house…. Leave my father alone,” Narges continued. “After they finally took Taghi, my little girl, Kiana spread out on the cold mosaic tiles of the foyer and as tears streamed down her face she asked for her father. I was helpless and like a stone statue gazed at my four-year‐old daughter, not knowing what to do… I am a human being, a mother, a wife, how much more of this pain and suffering must I go through.”

Children with parents who are prisoners of conscience are particularly affected negatively when they witness injustice; especially as they feel unable to rescue or help the parent who has been affected by court decisions outside of their control. Often parents who are prisoners, especially prisoners of conscience, feel great frustration and guilt in not being able to help their children who are left without them and the daily comfort of a parent’s presence.

“When Kiana was born I underwent a C-‐ section. I had many stitches on my stomach but the warmth of Kiana’s little precious body pressed against mine healed my wounds,” shared Mohammadi in a ‘heart-felt’ letter given to Iranian government officials quoting her experience as a mother. “When Kiana was only 3 years old she had to undergo surgery on her stomach and she too had many stitches that needed to be cared for and healed. I was her mother and it was my duty to care for her and nurse her back to health but I was arrested and taken to prison. I was not there to care for her and heal her as she had healed me,” added Mohammadi.

“The Iranian Government wants to break peoples’ spirits, they want to set an

example”, explained Christy Fujio, former immigration attorney and Asylum

Program Director for Physicians for Human Rights,

“The suffering caused by enforced disappearances, prolonged solitary confinement and other ill treatment and lengthy prison terms does not stop at the prison gate,” says Amnesty International. Family members of those who are imprisoned suffer from conditions of long term anxiety, depression and fear. These symptoms are especially severe for women and their families, especially the children.

“We have to speak of hope and love…,” said Narges Mohamaddi in response to her award in 2009. “Everyone has the right to Freedom of Speech and Thought: Article 19 of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights,” she added.