WUNRN

SYRIA - WOMAN'S PERSONAL STORY OF

FAMILY CRISES OF CRACKDOWN

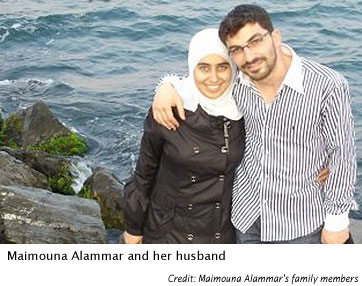

The Syrian crackdown has cost 4,000 lives by a U.N. estimate. Maimouna Alammar offers this account--beginning with a strange phone call from her brother--of how it's been devastating her own family.

(WOMENSENEWS)--I was

home alone with my 5-month-old daughter, Emar. My mother and mother-in-law had

left. The phone kept ringing. I wanted to break it.

(WOMENSENEWS)--I was

home alone with my 5-month-old daughter, Emar. My mother and mother-in-law had

left. The phone kept ringing. I wanted to break it.

I live in Daraya, a suburb of

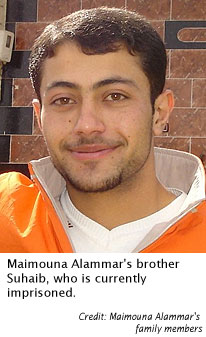

Around 6:30 p.m. my brother Suhaib, 22, two years my junior, called.

"I'm coming over."

"Power's out," I said.

The regime shuts off the electricity whenever they're about to clamp down on an area. I wanted him to understand that it wasn't the right time to visit, but because of the police state, not me. I'd delight in seeing him, and so would the baby.

The expected hour passed and he did not arrive. The phone rang again. It was my mother, worrying about Suhaib. Dad was still in prison. At dawn on Sept. 17, they'd dragged him off over mom's cries. He has taught nonviolence for decades. I grew up in a family committed to the sacredness of human life.

"Suhaib just called asking what your father-in-law's name is. They must have him at a checkpoint," my mom said.

"I'll call him."

Suhaib answered. From his voice I thought he was OK but, strangely, I couldn't hear the usual bus-stop background noises of a checkpoint.

"I need your father-in-law's name," he said.

I lost it. Suhaib sometimes does and says things at the wrong time. "Why do you need it just now? It's Ahmed, already!"

"I'll be there soon, Maimouna," he said.

A Baby Named

'Freedom'

I put the baby to bed. My husband, Osama Nassar, had been in prison when Emar was born on June 10. I held off naming her so we could name our first child together. They released Osama June 27. "Emar" is a Sumerian word meaning "freedom."

The doorbell rang. Before I got there, it rang a second time. Whoever was behind the door was impatient. Suddenly I wondered if it could be state police. I peeked through the hole: Suhaib stood there. It was dark; I barely saw the frown on his face. Behind him, on the landing, was another figure that I didn't examine closely.

As I started to open the door, a huge, lightly-bearded middle-aged man who'd been hiding shoved his way in, holding a gun against Suhaib's head. "Where is your husband," he screamed.

I tried to push the door shut against him, saying, "Wait! I'm not dressed! Wait until I put on my headscarf." I ran to the bedroom for it.

He was right behind me, gripping Suhaib. Another armed man started searching the house.

The large bearded man, pointing the gun at Suhaib, asked, "Where's your husband?"

"I don't know.

He's left the house."

"I don't know.

He's left the house."

"When?"

"He had been detained. After they released him, he left the house."

He sneered with mockery. "Oh, detained? Does that mean he has an opinion and a conscience?"

I didn't reply. Did an agent in a police state know the meaning of having an opinion or the significance of having a conscience?

He said, "Your husband killed three government security agents."

"My husband didn't kill anyone. My husband doesn't believe in killing." Osama and I met through attending nonviolence study circles. His whole life has been about believing that people can change themselves and their world nonviolently.

He snapped, "I will kill you."

'Killing Isn't the

Answer'

Emar stirred in her crib. "Killing isn't the answer," I said.

He said, calmer, "You're against killing? So what's the answer, in your view?"

I felt that my words woke the human side in him. I said, "We shouldn't shed blood."

Maybe he forgot himself for a moment. In a police state the police are not supposed to engage with citizens; it might bring a sense of humanity to the interchange. Emar gurgled.

The man leaned over her crib--that's when my heart dropped--and picked up my cell phone, which lay on my bed.

Emar smiled at me, eyes wide and curious. If this were happening in the city

of

"What do I press to find your husband's number?"

I didn't say anything. I looked him in the eye, trying to call out any goodness in him.

"If you won't answer me, we'll take your baby daughter until your husband surrenders."

"For shame," I said, picking up Emar, thinking, over my dead body. I looked at him over her soft cheek. "Please don't."

He said, "Then isn't it also wrong to kill people?"

I said, "We didn't kill any. We don't kill people."

He replied, "OK. I'm leaving her with you, just to show I'm human."

I lucked out. Layal Askar, Ola Jablawi, Hamza Khatib, Tamer Share, Ibrahim Shayban, my cousin Zuhair--these are a few of the murdered children of Syria; names I know both from personal contacts and press reports.

The man then grabbed Suhaib's arm. "If your husband doesn't surrender, I'll bring your brother back in a coffin."

I wanted to throw my arms around Suhaib, to stop them from taking him, but there was Emar to think about. I could put myself between Emar and the police, or Suhaib and the police, but not both.

I at last blurted, "My brother didn't do anything. It's my husband you want. Leave my brother alone!"

Suhaib called out to me: "Maimouna, tell…." but was silenced by a slap and a loud, "Shut up, idiot!"

I will tell the world for you, brother. God protect you.

My brother was taken away and is still in prison.

God help all my brothers, all my sisters, all our children in