WUNRN

Women News Network

Website Link Includes Video.

NEPAL - HISTORIC CUSTOM OF

CHHAUPADI ISOLATION OF GIRLS & WOMEN DURING MENSTRUATION & AFTER BIRTH

- DANGERS FOR HEALTH, SURVIVAL

The centuries old practice of chhaupadi in

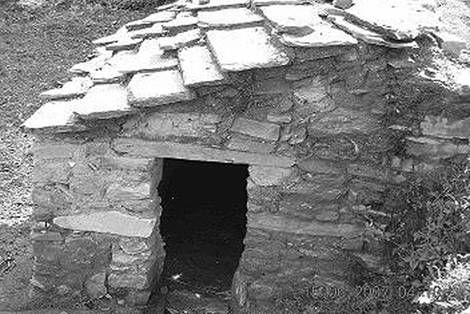

Stone chhaupadi hut -

Chhaupadi pratha, or ritual practice, places Nepali women and girls in a limbo of isolation. In history it is a practice that has been largely accepted. The word chhaupadi, translates in the Achham local Raute dialect as ‘chhau’ which means menstruation and ‘padi’ – woman.

Today the ritual of banishment surrounding chhaupadi still affects girls and women on all levels of Nepali society.

This dangerous practice also isolates woman during and after childbirth as they are banished for up to eleven days away from family members, causing critical danger and increasing complications that can, and do, lead to maternal and child mortality due to the possibility of excessive bleeding and asepsis following labour.

A chhaupadi shed or hut, also called chhaupadi goth, is a rudimentary stone, grass or stick shelter. Most shelters, many which are also commonly used as cow or goat sheds, have dirt floors and no windows. Many sheds have no water. Habitation by humans in these sheds can create dangerous situations as structures can reach below freezing temperatures in the winter and sweltering temperatures in the summer.

The January 2010 death of forty year old Belu Damai is a case in

point. Damai was found dead on January 3rd in a chhaupadi (menstrual) shed in

Bhairabsthan (VDC-8) in

Damai’s death was part of a larger event. Cold temperatures in Northern

India,

“Temperatures dropped to 30 °F (-1 °C) for several nights in the region,

with daily mean temperatures 11 °F to 18 °F ( 6 °C to 10 °C) below normal”,

said the National Climatic Data Center at NOAA – National Oceanic and

Atmospheric Administration in its 2010 report. “Up to four inches (10 cm) of

snow was reported along lower elevations in

‘Nachhunu‘, the Nepali word for menstruation, also translates as

‘untouchable’. Even in modern

“They packed some of my dresses and told my dad to go out of (the) house so that I couldn’t see him. I went with our house maid to her home which was approximately 1 ½ hours away. While there, I was given a dark room with no sunlight and given one plate and glass to use for eating”. – Nilima Raut

“I noticed changes occurring in my body and this was a very weird experience

for me”, says WNN correspondent in

The taboo associated with this natural process for women has contributed to

a widespread lack of knowledge about physical hygiene and female menstruation,

especially in the rural areas of

According to

Public service advertisements in

“Neither women’s activist groups nor the (

Girls who have their first cycle of menses often face, for the very first time, harsh restrictions based on superstitions. On the start of their menarche they suddenly cannot touch any males, including their father and brothers. They cannot cross a bridge. They are barred from entering their own home. They cannot speak loudly. They cannot perform their usual errands as their menses may cause them to poison or ‘taint’ whatever they touch.

Not all girls stay in a chhaupadi goth (shed) during menarche. Some are sent away to another home or location. While more affluent educated Nepali families do not place their daughters outside in sheds during the cycle of their menses, many of these daughters are also often isolated away from family members and the comfort of home.

“They packed some of my dresses and told my dad to go out of (the) house so that I couldn’t see him. I went with our house maid to her home which was approximately 1 ½ hours away”, said Raut. “While there, I was given a dark room with no sunlight and given one plate and glass to use for eating”.

Asked to use separate eating utensils, girls are also not allowed to enter any kitchen or home prayer room for twenty-two days. Looking in the mirror during menstruation is also considered bad luck. The list of restrictions is long and debilitating.

“Our culture has the superstitious belief that menstruation is the punishment of sins from our previous lives”, explained Raut.

To ‘protect’ relatives and neighbors from any ‘ills’ of exposure to a girl, some chhaupadi sheds are built as far away from the family home as possible. The distance can be as far as one mile away.

“On ‘those days’, I was kept away from school and feared what questions my friends and teachers would ask”, continued Raut. “I saw many of my friends miss school during their menstrual periods; I also saw some friends get married after they started menstruating because they were now considered ‘grown up’. . .”.

Even though a September 2005 Nepal Supreme Court decision ordered the government to enact a law “abolishing the practice of chhaupadi”, the court rule has been largely ineffective.

Today the human rights crime of chhaupadi continues with impunity in

numerous locations, especially rural

Often given only a small area of straw grass to sleep on and little to no blanket, girls and women who have been banished to outside sheds during the winter months can reach a state of critical medical emergency. Hypothermia during winter months is a stark and real possibility.

“Our culture has the superstitious belief that menstruation is the punishment of sins from our previous lives”. – Nilima Raut

“When exposed to cold temperatures, your body begins to lose heat faster than it can be produced. Prolonged exposure to cold will eventually use up your body’s stored energy. The result is hypothermia, or abnormally low body temperature”, outlined a United States CDC – Center for Disease Control – Emergency Preparedness & Response report.

“Body temperature that is too low affects the brain, making the victim unable to think clearly or move well. This makes hypothermia particularly dangerous because a person may not know it is happening and won’t be able to do anything about it”, continued the report by the CDC.

Dehydration caused by inadequate water in many sheds can also be a precursor to heat stroke in the summer season with symptoms of extreme nausea, headaches, vomiting and acute lowered blood pressure.

“Days were so hard; all of the restrictions were the worst part”, said Raut. “At the time, I had to use rags because I didn’t even know there were things like sanitary pads”, she continued. “Using rags was unhygienic and I was also unaware of how to wash them carefully”.

Suffering from a ‘culture of silence’ covering female reproductive

education, girls in

Public health education in

Govinda Raj Sedhai, secretary of District Education Office in Dolakha agrees. The education ministry is hoping to establish a new annual literacy plan in the region; including three days of health education classes dedicated exclusively to reproductive health and menstruation hygiene.

Chhaupadi ritual and culture can be a serious ‘matter of life and death’ for

many girls and women in

Two weeks after the 2010 death of Belu Damai, another chhaupadi death

occurred in