WUNRN

Women News Network - WNN

INDIA - TRIBAL MINER TUBERCULOSIS

DEATHS CREATE

ALARMING INCREASE IN RURAL

VILLAGE POOR WIDOWS

January 13, 2011

Shuriah Niazi – Women News Network – WNN

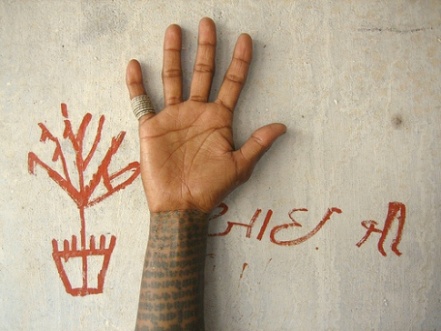

The hand of a Rabari tribal woman from

Majhera Village, India: Because of the

deaths of so many miners, India’s village of Majhera, in the Shivpuri District

inside the State of Madhya Pradesh, is now called the, “village of widows.”

One Saharia tribal widow, in the

Saharia tribal women have only a 7%

literacy rate. Because of this, finding employment that will support their

family after the death of their husband is almost impossible.

Madhya Pradesh, one of the largest states

in India with the highest percentage (14.5%) of ‘Scheduled Tribes,’ also known

at the Adivasi, is the home of the one of India’s most ancient people known as

the ‘Saharia.’ Living under extreme poverty, that has included a history of

death by hunger, the Saharia are a growing part of

Another miner, Suresh, the husband of 40

year old Saharia woman, Bhagwati, has also passed away. He death has left

Bhagwati with mounting pressure to care for herself and her family. The cause

of death is tuberculosis, that has been exacerbated by the culture of illegal

mining in

Without her husband Bhagwati’s resources

are gone. Many miners wives work alongside their husbands with their children

scavenging the tailings and wastes dumps that often surround the illegal mines.

With the rising weight of poverty in

villages inside Madhya Pradesh malnutrition is also on the rise. Malnutrition

numbers in the region have gone up from 53.55% to 60%. The issue of hunger is a

condition that comes with many illegal mines, as workers face extreme low

wages, uncertain work, mining accidents and the fatal cost of related

illnesses.

“Because miners often live in crowded

conditions, work long hours without enough food, and have little access to

health care or medicines, they have a high risk of getting TB,” said a 2009 report

by Hesperian Foundation, a global grassroots educational publisher for public

health.

Contamination of water in mining areas is

also an issue. “…communities and workers are forced to consume contaminated

water or live without a water facility as ground water is badly depleted due to

mining,” says the advocacy group MM&P – Mines, Minerals & People, a

growing alliance of individuals, institutions and communities who are concerned

and affected by mining in India.

Thirty-seven year old Anandi Bai, another

Saharia widow whose husband worked as an illegal miner, is another part of the

casualty of the rising TB epidemic. The loss of her husband, Ramlal, has left

her and her family with little health care access or food security.

Without husbands, many widows, are thrown

immediately into being single ‘heads of household,’ adrift in a world where

poverty becomes much more severe as they try to face society without their

husbands. Because of this, other dangers to women can occur. False job offers

can turn into sex-trafficking or labour bondage. These dangers are true for

widows as well as their daughters.

Coal miners sit outside the entrance to a mine in

“To be able to survive economically, the

widows go to the quarries themselves and run the risk to get the disease that

caused the death of their husband,” says a June 2010 report by the India

Committee of the

In illegal mines producing the mineral

silica, a condition called Silicosis has become common among workers. Silicosis

comes from extended exposure to rock powder dust that contains the mineral. The

symptoms and prognosis with the disease closely mimic tuberculosis.

The critical rise in TB deaths in Majhera’s

illegal mining community is now exposing the impact fall-out of sub-standard

conditions and corrupt mining policies to regions outside Madhya Pradesh. In

spite of an outcry by labour advocates, illegal mining of iron ore, coal,

silica, copper and other minerals has been on the rise throughout

Because of this, illegal use of children in

child labour and the misuse of women as stone labourers has been brought to the

attention of advocacy groups.

HIV/AIDS, is also among the health

challenges miner families face today. As mining industries attract women

sex-workers who congregate in regions close to the mines, miners who have

contracted the disease bring HIV/AIDS home to their wives. The incidence of

HIV/AIDS in the region may also be contributing to TB deaths. Further studies

need to be made.

Kamla, Bhagwati and Anandi Bai are not the

only women of the Majhera village whose miner husbands have died from

tuberculosis. In Majhera village alone, a shocking total of 92 widows are now

suffering the consequences of their husbands deaths to TB.

Although exact numbers of TB deaths in the

region have not been formally assessed among the tribals, numbers are

desperately needed to enable pro-active health programs and better legislation

to be put into place in

“My state, Madhya Pradesh, has the highest

level of malnutrition in the country, especially among Scheduled Castes and

Scheduled Tribes, but the government has just not woken up to the issue,” said

Yogesh Kumar, executive director of the Samarthan Centre for Development

Support in Bhopal.

TB – tuberculosis, is a disease that has

been known to be communicable in some forms and can be extremely debilitating.

In cases where nutrition is low, and treatment is limited, it is often fatal.

Fatalities are common especially if the disease is a virulent form of TB called

MDR-TB, multi-drug resistant tuberculosis.

“All of them (the miners who are suffering)

are Saharia tribal,” says KS Mishra, who is district chairman of a combined

group of 17 regional organizations known as Jan Adhikar Manch. “Life is very

difficult for them,” adds Mishra. “They work in illegal mines for their

livelihood and easily fall and succumb to a disease like TB, as they are malnourished

in the absence of an adequate diet.”

Free medicines, provided by government

hospitals for the treatment of tuberculosis, are part of

Not all victims of the tuberculosis crisis

in the mines are male. Wives of miners and their children are also contracting

the disease.

“Women don’t have a problem saying they

have malaria or chikungunya, asthma or high blood pressure and diabetes for

that matter – it is even fashionable to say so. But the infectious nature of TB

and the social stigma attached to it frighten women from approaching a doctor

in the initial stages when it is easier to cure the disease,” says

“Wives rarely seek medical help until TB is

in a very advanced stage. By this time the disease takes longer and needs more

intensive medical treatment to cure,” MedIndia explains. A visit to the

“It is difficult for these people to even

arrange two square meals (a day),” says Sachin Kuma Jain of the Right to Food

Campaign. “Even if they get the medicine for TB from the hospital it doesn’t

have the desired effect in the absence of a sufficient diet,” he explains. “At

the same time they do not take the full dose of medicines, and have to pay for

it with their life.”

Shivpuri’s district TB officer Dr. RK Jain

suggests generally the people in the area believe that traditional Ayurveda

herbal plant based treatment is the best. Even when western medical treatment

can be made available, many tribals do not trust medical doctors.

With a shortage of health workers in the

region surrounding Majhera it is not uncommon for health workers to visit the

area only once every 3 months to make assessments. Medical doctors are often

virtually non-existent in the rural areas.

In an answer to illegal mining in

“The penalties need to be made stringent,

at least in line with those of other similar Acts, so that the offender is not

let off with a token penalty, as is mostly the case. Hence penalties have been

enhanced by about 100 times,” stressed

To aid the miners and their families, Ms.

Ganeshi Bai, of Majhera village, has been assigned to the region as one of the

local health workers. The problem that she herself is a labourer, who has to

leave for work in order to earn her livelihood, presents another flaw in the

system.

“While a small section of the population in

Madhya Pradesh continues to bask in the glory of development, the majority is

still struggling for the bare necessities,” reminds the Asian Legal Resource

Centre in a March 2010 report.