WUNRN

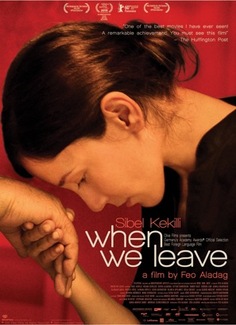

"WHEN WE LEAVE" FILM

SEGMENT

WHEN WE LEAVE - Film - Fleeing an

Abusive Marriage

German-born Umay flees her oppressive marriage in Istanbul, taking her young son Cem with her. She hopes to find a better life with her family in Berlin, but her unexpected arrival creates intense conflict. Her family is trapped in their conventions, torn between their love for her and the traditional values of their community. Ultimately they decide to return Cem to his father in Turkey. To keep her son, Umay is forced to move again. She finds the inner strength to build a new life for herself and Cem, but her need for her family's love drives her to a series of ill-fated attempts at reconciliation. What Umay doesn't realize is just how deep the wounds have gone and how dangerous her struggle for self-determination has become... Written by Independent Artists Filmproduktion ______________________________________________________________________

http://thewip.net/contributors/2011/01/the_best_of_2010_an_interview.html

An Interview with When

We Leave Film Writer, Director, and Producer Feo Aladag

By Jessica Mosby - January 25, 2011

Rarely does a film come along that floors you in its perfection

and then continues to resonate for months after that first viewing. I saw the

German film When We Leave

at the 2010 Tribeca Film Festival, where it won best film in the world

narrative feature competition. When I entered the theater at Tribeca, I had no

expectations about the movie. But two hours later I could not stop thinking and

talking about what I had just watched. Writer, Director, and Producer Feo

Aladag flawlessly couples the humanistic and thriller elements of filmmaking to

create a cinematic force that makes you care about the characters while sitting

on the edge of your seat fearful of what will happen next.

When We Leave begins

with Umay (Sibel Kekilli) fleeing her abusive husband Kemal (Ufuk Bayraktar) by

leaving

Even after her family’s rejection, Umay is unable to completely break familial ties. She is torn between a life free of traditional Islamic values and her family’s approval and acceptance. While Umay is struggling to start a new life for herself and Cem, her family is also reeling from the consequences of their decision to reject their own daughter. As her characters transform and evolve, Aladag’s direction creates an ominous tone that builds until the film’s unexpected finale.

When We Leave is

When Aladag – best known as an actress – was in California to promote When We Leave during its screenings at the Mill Valley Film Festival, we spoke about her filmmaking process, her commitment to authenticity, and the movie’s international reception.

I know this is your debut film behind the camera. How did you

conceive the idea to write, direct, and produce When

We Leave?

It seemed like a natural decision when I knew I wanted to tell

this story. It was just clear that I wanted to direct this - it wouldn’t be

just writing [the screenplay]. Producing it came about because I wanted

complete creative independence. To me - acting, writing, and directing - they

are just different forms of expression deriving from the need to communicate.

When writing the script

how did you balance the more personal narrative with the thriller tone?

I tried to create a core that would be emotionally true in a universal sense, keep it interesting, and keep it flowing for an audience. In a way [the story is] like a Greek tragedy, working in a very classical way of structuring the story. You just try to create true moments in the script. Coming from acting helped me a great deal in the sense that you have a very clear feeling about the rhythm of a scene and the dialogue, and just creating characters and moments that feel true.

Did you write the script with particular actors in mind?

No. Absolutely no. I had a very long casting process. I was pretty

sure that I wanted to work with – for the parts of the parents – actors from

I did a very long process of street casting for the brother and sister, the child, and also for the part of Umay, actually. It’s been quite a mixture of conventional casting processes – national, but also in Turkey, in Switzerland, in France, in Austria – combined with an extensive street casting process that went over one and a half years.

By “street casting” do

you mean that you were approaching people on the street who did not necessarily

have an acting background?

That’s correct. I wanted to work, especially with the young people, with people we had not seen before. I was interested in finding new faces, and in finding people with no acting experience and bringing them together with people who would bring a lot of acting experience to the table. I had a very heterogeneous ensemble in mind, and that worked out really well.

We really invested a lot of time and effort in casting on the street. We had tons of people working on this – I had more than 2,000 people being interviewed. And actually I just asked them small questions and looked them in the eye, and then I narrowed that down. Gradually we went to a more conventional casting process. I had quite a big group of young people I did a [acting] workshop with over a period of time – meeting a couple of times a week and working with them based on my [acting] technique. And [then] we narrowed that group down again. With those [people] I eventually had in a very small group, I worked for four months in order to let them be a family. Even if you don’t have scenes on screen together, I thought it was very important if I’m portraying a family that it’s people here who really know each other.

It was very interesting for me to work on this very strictly orchestrated script. I wanted to stick to [the script] in a very exact way, but still give actors – especially people with no acting background – the tools to be true in the moment and to really react in the moment based on the words in the script. It was a very rewarding process in itself.

After you cast the principal characters you then worked with

them for four months before you started filming?

Well I worked with those people who had never acted before for four months. I was trying to provide them with some tools. If you work with people who have no acting background whatsoever, I think it’s important for them to feel protected and to feel safe in the environment of filming. There is so much pressure when you have sixty people watching you and you’ve never acted before. I tried to teach them whatever I could, and I tried to bring people in who could [also] teach them.

Then how long did the

actual filming take?

We filmed 38 days altogether. We shot in two countries; we shot in

How has the film been received? Are you concerned that the film

will be perceived as being anti-Islamic?

No, and it hasn’t so far. I think what was my problem with the media coverage on those issues was that there was a lot of black and white painting going on. People were not being portrayed in a humanistic way. Approaching all of the characters with empathy helped that minorities didn’t feel that they had been portrayed in a way they wouldn’t like to be portrayed. You do see how much the father is suffering and you do see how much the older brother is suffering. They are torn. I think it helped that people didn’t feel they had been portrayed in a wrong way.

I even experienced that in

What has the reaction to the film been in your home country of

I feel really blessed and privileged. We have shown the film in 28

countries since its release in the spring in

In