WUNRN

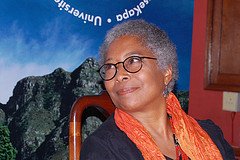

Alice Walker Lecture & Spirit in South Africa

By Liesl on September 13, 2010

Report by Liesl Jobson

The 11th Steve Biko Memorial Lecture, given this year

by literary icon Alice Walker, was warmly received last week by a capacity

crowd, including poets, writers, academics and public intellectuals. In a

somewhat unanticipated note of ceremony, the evening commenced with the

national anthem ringing out in UCT’s Jameson Hall. The diminutive

The reason for the author’s request for this

formality soon became evident. Like a call and response spiritual, her stirring

address was structured lyrically around Nkosi sikelel’ iAfrica. In a

true, clear voice she sang the opening stanza of the national anthem, recalling

how at the age of five, her sister Mamie Lee taught it to her on her return

from college to the racially segregated Eatonton, Georgia.

She counterpointed tender observations (“You are so lovely. So lovely. It is this loveliness who you deeply are… as so many of us have forgotten that we are beautiful”) with stern rebukes (“I am unable to comprehend how you now have a president who has three wives and twenty-odd children”) and hard questions (“… that Bill Clinton, who could not respond to the genocide of 800 000 Rwandans, and even De Klerk are going down in history as more honorable, more smiled-upon, by many South Africans than Winnie Mandela. How can this be?”).

The melody of Nkosi interlinked with her words on gender (“The African way with women leaves much to be desired. And I am not faulting only the men, some women are content to be ‘potted plants’”); her consternation about the planet (“We have entered a period of such instability and impoverishment of spirit that even though charged with our soul care, our ministers, our teachers, our spiritual guides, are themselves also in a state of fright. Never before has humanity faced losing the earth itself, which is exactly what we are losing as global warming increases, and as greater climate disasters affect us worldwide”); and her exhortation, despite all of this, to dance.

Noting how our governments don’t not hear our

cries for a better way to exist,

Her talk, which she introduced as “Coming to See You Since I was 5 Years Old: A Poet’s Connection to the South African Soul” received a resounding standing ovation.

At the press conference that followed,

She spoke of women’s collusion: “There has to be

in woman, herself, her resident rebel that claims her life as sacred; that

no-one can abuse and misuse. We must fight for that. We must hold that really

dear. It could be that a lot of that fight has been beaten out of women. That

happens, but I would like to see much more resistance.” She referred to her

novel, The Secret of Joy, which asks what the secret of joy is. On the

final page, the narrative offers the answer: resistance.

She spoke about Women for Women International, an organisation that (amongst other things) supports women in the DRC to rebuild their lives. Referring to the appalling incidence of violence against women, she pointed out the communal responsibility and opportunity for the individual to attend: “To not be involved, if you have any feeling for what is happening, is really bad for all women. We can stop it, but we have to be present to it.”

She called for wariness around the “gadgets drowning out our inner voices”. The artist, potentially as influential with our children as our mothers, can speak to this and show how you lose yourself if you are constantly responding to something external. You can’t hold onto yourself. How would you? A lot of the confusion on the planet is due to our having lost inner direction. We don’t know where we are. The world, the earth is being stolen faster and faster because we’re not there to attend to it. We’re distracted. Young people can grasp this. As adults who know there’s an inner space for us, we have to be determined to have it, to do it.”

She spoke on TV: “If you develop a sense of yourself as ‘clean’, if you want cleanliness about your aura, your psyche, you don’t want to sit anywhere and have people throw all their madness, fantasies and craziness all over you on a daily basis, and this is what’s been happening to humanity. What’s scary is that people often don’t have a clue that their dreams are being stolen through distortion. When you soak up everybody else’s garbage, it goes into your psyce. Your psyche loses the way. It has no idea what’s happening because it experiences these fantasies as real.