WUNRN

NE AFGHANISTAN - WORST RECORDED RATE

OF MATERNAL MORTALITY

LINK INCLUDES DOCUMENTARY VIDEO.

|

By Lyse Doucet

|

Muslima shyly tells me she is 25. It is hard to believe.Her brown eyes stare from a freckled face partly hidden by a patterned red head scarf. She looks about 15-years-old.

Whatever age Muslima is, she

has triumphed over the odds. She survived one of

|

For many women a visit to the clinic

means days of walking |

Badakshan

province, in north-east

A smiling Muslima cradles her newborn baby girl in the folds of her long scarf as she sits up in bed in a maternal ward in the capital Faizabad.

It is the best Badakshan has to offer. When the first obstetric gynaecologist, Dr Hajira, arrived here 17 years ago, there was only one room and four beds for the entire province.

"Fifty percent of the women who come here are in a bad state," she explains. "If this hospital wasn't here, they would all die."

Thanks to international aid since the fall of the Taliban in 2001, there is a two-storey concrete block of a maternal ward.

Carried on planks

A visit to even one room on Dr Hajira's morning round tells the story of women's lives here.

Muslima, and Qamanesa in the bed next to her, look far too young to be bearing children.

|

Lack of paved roads makes travelling in

Badakshan difficult |

In the other corner, Monisa is fighting for her life. In her early 40s, she is in her 14th pregnancy. Five of her children have already died.

Later that day, her five-month old foetus is delivered, dead. But Monisa pulls through despite a weak heart.

Changing the fate of women in childbirth means changing so much of life here. There is no electricity, no running water, no paved roads.

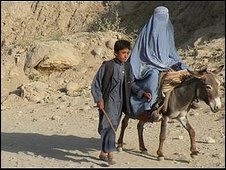

Outside the capital, a trip to the clinic - if it exists - can mean walking for days, travelling by donkey, or if the family can scrape together enough money, by car.

Many women are carried on wooden planks or ladders supported by four men, including an anxious husband.

Lack of infrastructure

In the remote district of

Shahr-e Bozorg, survival can come down to luck.

|

|

Sadiya had been in labour for 12 hours and was bleeding heavily when one of the few trained midwives, with the only ambulance in the region, happened to stop by her house in her village of Chowgany.

She was rushed to the only maternal clinic in the area providing emergency care.

"Will she make it?" I ask Simin Walid of the British charity Merlin which runs the clinic. "We hope," she replies, striding into the simple delivery room in the concrete bungalow.

Even gleaming ambulances find it hard to make haste. The gruelling, bone-jarring journey unfolds along narrow bumpy paths clinging to the mountainside or across rocky river beds.

The vistas are spectacular to behold, but forbidding. Even the Taliban did not conquer this area when they ruled Afghanistan.

Traditional midwives

When winter sets in, villages scattered across the undulating mountains are cut off.

|

Community midwifery training will help

save women's lives |

In Sadiya's village, most women deliver at home or turn to a traditional midwife like Gulnar.

"I've delivered hundreds

of babies," boasts the beaming Gulnar as we sit in a shaded courtyard in a

mud-walled compound.

But she regrets her illiteracy and lack of any formal training: "My hand is under a rock," she says.

And when I ask her how many mothers die in childbirth her animated smile disappears: "Many, many" is her calculation.

But these are lives ruled by God, not gynaecology.

"Some lives are short, some are long," Gulnar reflects with a stoicism shared by every Afghan we met on our journey.

It is just the way life is. But some are trying to change it.

Education and training

Dr Hajira uses a similar turn of phrase with a more resolute twist: "I prefer to live a short life that's full, than a long one," she says.

Born in Faizabad, her father, the province's first doctor, insisted she go to school even though she was the only girl in a class full of boys.

She has dedicated her life to helping save women's lives.

And a new army of midwives is slowly being trained to start bringing modern practises to this battle. In a programme run by the Aga Khan Foundation, young women are chosen by their villages, given approval by their husbands or fathers, and come to Faizabad for an 18-month course.

Eighteen-year-old Masuma , already a mother with two children, will return to her village in Shahr-e Bozorg.

"It was a community decision and I want to be a midwife to serve my people," she says.

She and a dozen other young women in white medical coats and pale blue caps watch intently as their teacher Farzana Darakhuna demonstrates with a rubber infant how to deliver a baby safely.

Farzana sees progress: "In the past, men wouldn't think of taking their wife to a clinic. They used to think if they took her there, there might be many men, and her dignity wouldn't be protected."

In this conservative society,

changing women's lives means changing men's too.

================================================================

To contact the list administrator, or to leave the list, send an email to:

wunrn_listserve-request@lists.wunrn.com. Thank you.