WUNRN

Women News Network

August 19, 2009

Zambia - Acid Crime Survival

Women face extreme violence from acid

- Correspondent SALLY CHIWAMA – Women News

Network – WNN

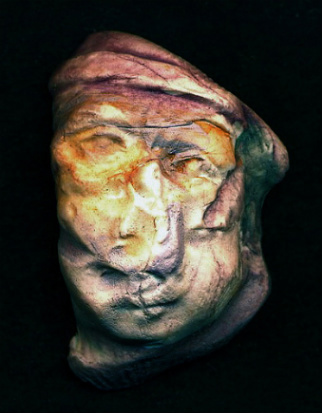

Artwork by sculptor Theo Junior - 2009

“I didn’t realize that the tongue skin was

also peeling off. The young girl was pushing something in her mouth. I opened

her mouth to see and found that almost the whole tongue had come off. I had to

pull it out like you do with a cow and only a little red thing (tongue)

remained.”

These excruciating words by a girl’s older

sister describe the aftermath of the worse physical attack a 13 yr old could

ever experience.

What happened to 13 yr old Fridah Mwansa

(not her real name) has been happening to women and girls at an ever increasing

rate in

__________________

Acid - A Weapon of Choice

Nitric acid, sulphuric acid and/or

hydrochloric acid in the Central Asia and

Known to chemists as HNO3, nitric acid was originally

used in secret rocket fuel formulas by development scientists in

Today it is still one of the ingredients

used in jet fuel propellant. Nitric acid is also used primarily in the

manufacture of fertilizer, or in gold jewelry manufacturing to separate gold

from other metals.

“Red Fuming Nitric Acid,” is a key

substance used in the manufacture of Iraqi military Scud, Guidline, Silkworm

and Kyle missiles. Controversies with the toxic effects in causalities in the

use and deployment of these weapons of war increased during the US Gulf War

era. Today these weapons are still in use. The production of acid in chemical

manufacturing facilities has also held some of the

responsibility for troubles with today’s global acid rain.

Although nitric acid is actively being

manufactured worldwide, especially in

“World nitric acid production in 2006 was

estimated at about 51 million metric tons,” says CHE – the Chemical Economics

Handbook Program, one of the world’s leading chemical reporting and marketing

agencies.

But how easy is it for anyone to buy? In the

“In Dhaka (

__________________

Interviewing an Acid Survivor

Interviewing an acid survivor is tricky.

The damage to victims is so severe, as a journalist myself, it’s hard not to

react personally to the story.

As Fridah’s sister, Annette, narrated her

excruciating story to me, her little sister Fridah sat close on my side, as if

she needed some kind of protection. She looked scared, vulnerable and alone. I

asked her if she wanted to tell me her whole story. Her answer came swiftly as

a tear dropped from the one good eye she had left.

“I don’t want to talk about it; I’m really

tired of this,” she said flatly.

I wondered; should I press her to tell me

exactly what she was tired of?

“It brings back very painful memories,” she

declared. “I can see the whole incident all over again, and very clearly, like

it happened yesterday”.

I sat patiently. All I could do was listen

and watch and take notes. She looked like her pain was excruciating. Half her

face was missing.

In 2002, in a small village 80 kilometers

from Lusaka, in the village of Mpika boma, 11 yr old Fridah was doing her

homework when she suddenly found out from her parents she was now “engaged” to

be married to a man many years her senior.

Her parents had already received the “insalamu” (dowry)

for their daughter, so the agreement was done. Two years, after Fridah

completed her primary education, the child would be handed over in a bridal

ceremony to her new husband, Thomas Chileshe.

With Fridah’s difficult news her older

sister, Annette, had another idea. She made plans for a rescue. Annette helped

Fridah move to the capital of

But Thomas Chileshe had other plans too,

even after the news that Fridah’s family wanted to annul all the marriage

arrangements, in a series of calculated moves he would do everything he could

in an attempt to force Fridah to be his wife.

“Listen Thomas, this relationship was made

in the village and not in

Thomas was hoping to take Fridah back home

to live with him right away. “This girl is here for school, so please make this

your last visit,” repeated Annette sternly to Chileshe.

__________________

Acid Crime and the Law

The need to pay attention to stories about

the brutal forms that acid attacks take is evident. Increasing numbers of

humanitarians and global rights activists are now rallying worldwide to bring

legislative sanctions to global acid violence perpetrators, underground acid

resellers, acid distributors and manufacturers.

The first case of reported acid attack in

the world happened in

To battle acid crime,

According to the Bangladesh Acid Crime

Control Act, if investigators of the crime neglect their duties in properly

collecting evidence or making witness reports, the investigators and

enforcement officers can also be sanctioned. The Acid Crime Control Tribunal in

___________________________________

Deception – Lies and

Intimidation

“He told me his mother was very ill and had

traveled to

“I asked him why his mother wanted to see

me and he said because she wanted to hear from me in person; to know whether it

was actually true that I wanted to discontinue the engagement,” added Fridah.

“He assured me that visiting her would only be for a short while. He would make

sure I got home safe and in good time.”

But lies come easy.

When Fridah arrived at the place where

Thomas was staying he invited the young girl quickly inside. As soon as she sat

down, Chileshe locked all the doors as he wrestled Fridah’s mobile phone from

her hand. In her youthful naïveté Fridah asked to see Thomas’ mother, but

Chileshe told her that she wasn’t in the house, that she was far away and

nowhere near them. She was back home in the village.

Fridah Mwansa before and after acid attack.

Image: Sally Chiwama

By that time, “my sister was (frantically)

calling me to try to find out my whereabouts,” said Fridah describing the

incident. “Thomas had gone outside with my phone locking me up inside,” Fridah

continued. “He dialed Annette, telling my sister that she would never see me

again because I was now his wife.”

At that point there was no going back.

In a chilling move, Thomas began using

Fridah’s mobile phone, in a form of texting crime, calling her bank of

relatives; her bothers, her sisters, her “Aunties;” telling them all they would

never see Fridah again; and that they shouldn’t bother looking for her because

he had married her.

Back at Annette’s home, Fridah’s sister was

in a panic as she called the Lusaka Police Service to report Fridah’s abduction

to the Victim Support Unit (VSU). “No, she didn’t know Chleshe’s location.”

The police thanked Annette for the

notification. The night was long and full of tears.

Next day, Thomas Chileshe’s sister-in-law

went to the house where Fridah lay captive. She tried to reason with her

brother-in-law through a window in the house asking him, why was he keeping

this child trapped without the consent of her guardians? She pleaded with him

to let the young girl go.

It worked. Thomas opened the door freeing

Fridah to walk home from her ordeal.

But Thomas never did let go.

“I went home alone and reported the entire

incident to the VSU,” said Fredah. “My family tried to find out if Thomas had

raped me. I told them the truth; that he never slept in the house while I was

there, but they wouldn’t believe me. In fact, I am still a virgin,” said Fridah

tearing.

It was after this that the text messages began.

“Nag banana Chachiine nkakwipaya,” was the

first message that suddenly appeared one afternoon on Fridah’s phone. It

translates a chilling message, “If it is true that you have denied me, I will

kill you.”

This message and the ones that followed

were reported one by one to

At first Fridah and her sister didn’t take

the messages seriously. They even laughed about many of the threats. But the

messages didn’t stop. They came more and more frequently as the ongoing tone of

violence from Thomas became more and more urgent.

Fridah tried to ignore the urgency in the

words. With each text message she tried to decide if she should save it and

show it to the VSU. She wished the whole thing would just wear off and go away.

What else could she do? The police could make no promises.

================================================================

To contact the list administrator, or to leave the list, send an email to:

wunrn_listserve-request@lists.wunrn.com. Thank you.