WUNRN

South Africa - Women

Bring Rapists to Justice

Nomthandazo Radebe, 20,

in downtown

In a country where 28 per cent of men admit to committing rape,

women are succeeding in demanding prosecution

Geoffrey

York

July. 17, 2009

When the rapist's aunt tried to settle the matter in the traditional way by offering two cows to the victim's mother, it was already too late to stop the women activists of Lusikisiki.

They had mobilized, and they were hunting for justice. They took to the streets with loudspeakers, placards and pamphlets. They went to the police station, the hospital, the courtrooms and the school.

They insisted on a police investigation, and they forced the police to bring in special rape kits to gather forensic evidence from the victim. They kept up the pressure in the courts.

It took almost two years, but the women won. On March 25, the rapist was convicted and sentenced to 13 years in prison – the toughest prison sentence ever imposed for rape in this region.

With more than 50,000 rapes reported annually – nearly 150 every

day – and many more cases that are never reported,

In a recent survey, 28 per cent of South African men admitted they had raped someone at least once in their lives. Almost three-quarters of them had committed their first rape before the age of 20.

The study, which surveyed a representative sample of men from

1,700 households in two South African provinces, concluded that sexual assault

is linked to

The study shocked many people in this country and around the

world, but it was no surprise to those who lived in Lusikisiki and similar

towns across

For years, the police here were taking these cases lightly, making little effort to punish the rapists, often accepting bribes and dropping cases before they went to court.

“Corruption is too high here,” said Nombeko Gqamane, administrator of the Lusikisiki office of Treatment Action Campaign, an advocacy group on HIV/AIDS and other health issues that fought hard to force the police to prosecute the rapist.

“When we analyze why the police are dragging their legs on rape cases, it's often because someone gave them 1,000 rand [about $140 Canadian],” she said. “Most of the dockets are lost. When we put pressure on them, they find the docket again.”

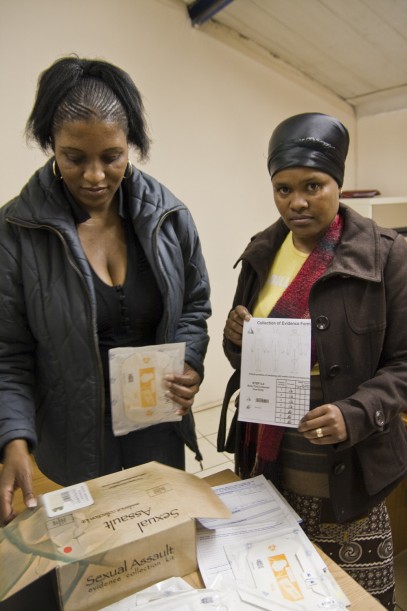

Activists Nombeko Gqamane and Tandeka Vinjwa organize a rape kit,

which includes forensic instruments and documents to be used by police in rape

investigations, at their office in

Until TAC opened its office in Lusikisiki in 2003, many rape cases

were routinely ignored by the police. “People were just paying with sheep or

goats, thinking that they could just keep it within the community,” Ms. Gqamane

said. “We want to change this culture. We say to people, ‘You have to go to the

police with these cases.'“ The turning point came on June 12, 2007, in the

As darkness fell that day, a soft-spoken high-school student named Nomthandazo Radebe was walking to a shop to buy paraffin. She was a shy, bespectacled 18-year-old.

A teenage boy – someone she knew from school – grabbed her and held a knife to her throat. He forced her into his house, wrapped a scarf around her mouth and, for the next eight hours, raped her repeatedly.

When the terrifying ordeal was over, Ms. Radebe called a friend who happened to be a TAC leader in the town. Together they went to the police station and to the hospital so that Ms. Radebe could be examined.

“The police were friendly and they took me to a separate room,” she recalled. “I thought they would investigate. But they didn't take it seriously. They didn't even want to get the evidence from the hospital.”

The women soon discovered the police did not have any rape kits. The kits, which provide the forensic instruments and legal documents necessary for a proper rape investigation, are supposed to be stocked at every police station in the country.

“The doctor at the hospital said he couldn't do anything without

the rape kit,” Ms. Gqamane said. “So it was our duty to put pressure on the

police.”

At the urging of TAC, the police agreed to get a supply of the kits from another town, and the kits arrived the next day. The problems, however, were just beginning.

“After six days, the TAC people came to me at home and asked if the police had visited me yet,” Ms. Radebe said. “But they hadn't come yet.”

The TAC volunteers went back to the police and insisted they investigate. But after two months, the first investigator in the case was transferred to another town. The second investigator went on vacation, and then on a training course, and nobody replaced him.

The police claimed they didn't have enough resources to

investigate all rape cases. Court appearances in the Radebe case were

repeatedly postponed because of the investigator's absence. The TAC activists

went to the police station repeatedly to look for the investigator, but he was

never there. They spoke to his supervisor and warned him that they would

publicize the inaction.

“One policeman came to see me, and then they disappeared,” Ms. Radebe said. “The investigator said he would look into the case, but he didn't. They didn't tell me anything. It was so sad. Only the TAC people kept visiting me.”

Meanwhile, the TAC activists were holding rallies – known as “mobilization days” – in the neighbourhood where Ms. Radebe and her rapist both lived. With loudspeakers, they urged the residents to break their silence and report any evidence of rape. They handed out leaflets and talked to anyone who came out to the street.

In her neighbourhood and at her school, Ms. Radebe was facing harassment and intimidation. “The friends of that boy kept calling me names and fighting with me,” she said. “They were saying, ‘She is lying, she was his lover, she has AIDS' – everything. Sometimes they came to school to try to beat me up. I had to stay in the classroom until they had gone home. It made me cry every time, but I never gave up.”

The TAC activists went to the school and spoke to the principal, who called in the rapist, who was still in school at that point. “We told him that he could be jailed for threatening her,” Ms. Gqamane said.

The student and his friends stopped harassing Ms. Radebe at school, but they continued to hurl insults at her in her neighbourhood, so TAC organized more rallies to defend her.

For each court appearance, TAC sent a dozen or more of its volunteers into the courtroom to provide moral support for Ms. Radebe, and to ensure that the case stayed alive, despite the long delays and despite the offers from the rapist's family to settle the case in the traditional manner.

“His family kept saying, ‘You can't take this to the police, it would be shameful, keep it in the family,” said Ms. Radebe's aunt, Queen Nonhlanhla. “In many cases, girls do not report a rape. But when your child is raped and harassed, you can't just accept a cow. These boys destroyed her life.”

The verdict finally came on March 25, when the court imposed the unprecedented 13-year prison sentence on the rapist, Sonwabo Mangcongoza. “Such an offence can never be tolerated by any community,” the judge said.

Ms. Radebe is convinced the rapist would never have been convicted if the TAC activists had not become involved in the case.

After the trial, she moved to the city of

“I don't want to go back home,” she says. “That boy says he will come out of jail and catch me.”

Six years after opening their office here, the TAC activists – six staff members, 27 paid volunteers and 900 active members who join the rallies and pickets – have begun to cure the rape epidemic in Lusikisiki.

“We've forced the police to be more visible, in daytime and at

night,” Ms. Gqamane said. “If we weren't here, more people would be victims of

these crimes. We can see the difference. It's working. People see the light

now.”

================================================================

To contact the list administrator, or to leave the list, send an email to:

wunrn_listserve-request@lists.wunrn.com. Thank you.