WUNRN

SERIOUS ALERT TO WOMEN TRAVELERS -

REFUSE TO CARRY ITEMS FROM STRANGERS - POTENTIAL DRUG CONTENTS - COULD LEAD TO

ARREST

AND EXTENDED INCARCERATION -

SECURITY CHECKS INCREASE

____________________________________________________________________

|

|

|

02/22/09 |

|

By

Dominique Soguel |

|

A Paraguayan was on her way home from Ecuador when a man persuaded her to carry bottles of shampoo on the plane. Now she's in a Quito detention facility with a growing number of women on drug charges. First of three stories about women in the jail. |

|

She never got back, though. As she left the call center, a young man approached her on the street and offered to sell her shampoo. The bottles had regular logos, she told Women's eNews, and the liquid was yellow. The young man sold her one bottle and then asked her to carry two bottles of shampoo to deliver in Buenos Aires, a layover in her flight to Paraguay. She resisted. He complained of heavy air mail fees and tried to cajole her. He threw his arms around her. He gave her a winning smile. He assured her that the contents were fine. He called her "mother." "He didn't even give me his name!" she said. "How was I to know the shampoo bottles had drugs?" Britez told her story from within the cornflower blue and egg yellow pavilion of Quito's Center for the Social Rehabilitation of Women, which functions as a jail for sentenced women; a detention point for those, such as Britez, waiting for a hearing; and a social rehabilitation facility providing technical training in a wide range of arts and crafts. Interpol agents apprehended Britez on Jan. 15 at the Quito international airport en route to Ciudad del Este, the capital of Paraguay. The shampoo containers held 13.475 grams of cocaine. Bustling

Free-Trade Zone

Ecuador is a bustling tariff-free trade zone but it is also a significant stopover in the international illicit drug trade with major producers--Colombia to the north and Peru to the south--pressuring its porous borders. Over half of the cocaine bound for the United States passes through Pacific waters off the Ecuadorean coast and follows routes through Central America, the Caribbean and Mexico. The United States Andean Trade Promotion and Drug Eradication Act, signed into law in 2002, is set to expire at the end of this year and could mark a turning point for U.S. foreign policy in the region. Since the 1990s the law--and an air base in Manta, Ecuador, used for anti-narcotics surveillance that was leased to the United States until the end of 2009--has been at the heart of cooperation between the two countries in the fight against the illegal trade in narcotics. After coming into office in 2007, Ecuador President Rafael Correa said he would not renew the air base contract when the lease ends. On Feb. 8 Correa ordered the expulsion of a U.S. customs official, accusing him of suspending aid to Ecuador's anti-narcotics programs. Despite a recent history of cooperation in the region, coca cultivation in the Andean countries of Bolivia, Colombia and Peru grew by an average of 16 percent in 2007, according to the United Nations' annual world drug report in 2008. Colombia is at the core of U.S. anti-narcotics efforts, yet the area of coca cultivation there expanded 27 percent to 99,000 hectares. Reliance on

'Mulas'

In recent years, traffickers have increasingly depended on women to serve as "mules" or "mulas" to help them transport their goods, according to Lt. Ramiro Martinez at the provincial headquarters of the national police's anti-narcotics department in Quito. In 2005, only two women were apprehended at Quito's airport, one foreign and one national. Since then the number has steadily increased. Every year, 15 to 20 U.S. citizens in Ecuador get caught trafficking drugs in their bodies or hidden suitcase panels, according to the U.S. State Department. In 2008, 24 women were apprehended at Quito's airport for attempting to traffic between one and five kilograms of cocaine or heroine. Ten were European and six came from Latin America. Eight were Ecuadorean nationals. In January, all three of the women arrested at the international airport in Quito were foreign. "Ever since immigration laws have hardened in the European Union and the United States, traffickers have been turning to alternative routes and targeting foreign women who are returning to their home countries and don't need visas, making transport simpler and scrutiny easer to evade," said Martinez. U.S. visa requirements, says Martinez, and border controls in Mexico have become tougher since the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. Similarly, Spain, which has served as Ecuadoreans' principal port of entry into Europe since the 1960s, has increasingly tightened immigration laws and cracked down on undocumented immigrants since 2001, despite previous waves of naturalization and amnesty. Martinez said Ecuador's own legal effort at cracking down on the illicit traffic of cocaine, heroin and marijuana began with a 1990 penal code that hardened penalties while blurring the distinction between trafficking, consumption and possession. Because of this article, Britez could face eight to 12 years in prison for trying to smuggle drugs out of the country. "The law is very harsh," said Martinez. "It makes no distinction if you are carrying 10 grams or 10 kilos." Similar Stories

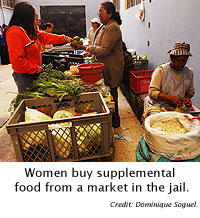

In interviews at the detention center, the two other women arrested in January at the international airport--Charmaine Graham from Jamaica and Renata Ferencova from the Czech Republic--both told Women's eNews that, like Britez, they were tricked into muling and did not know what they were carrying or the risks they were running. Less than half the women at the rehabilitation center--only 100 out of 264 in January--had court dates scheduled or had been sentenced. Some, according to William Yaranga, the jail's director, have spent years behind bars without seeing a judge. "The jail is full of women who can't afford lawyers," he said. "The big fish never lose their freedom." Britez says her lawyer is working toward her repatriation. Due to a bramble of international laws and her own lack of knowledge of Ecuadorean law, it is impossible for Britez to predict where she will be in three months; at best, she will be free in Paraguay or at worst still waiting for a sentence in Ecuador. Ecuador's drug laws are stiff by South American standards. One of Britez's best hopes is a pardon. Last year, President Correa set a precedent by pardoning 1,200 drug couriers. Offenders who carried less than two kilograms of any drug or substance and had already served 10 percent of their sentence, with a minimum of a year, were eligible. At the thought of her husband and seven children back in Paraguay, Britez starts crying and tapping her broken nails on the dirty, plastic white table at the center of the jail pavilion. She says she is hungry and running out of money. The facility provides one meal per day. Visiting relatives fill the gap. But Britez has none. "You pay for someone else," says the 45-year-old. "People trick you. You have to be very, very careful in life." |

================================================================

To contact the list administrator, or to leave the list, send an email to:

wunrn_listserve-request@lists.wunrn.com. Thank you.

She

says she wanted to tell her niece of her mother's death but once in Quito she

couldn't reach or find her. Two weeks later, Britez gave up and went to a

public call center to phone her husband and inform him of the details of her

return trip home.

She

says she wanted to tell her niece of her mother's death but once in Quito she

couldn't reach or find her. Two weeks later, Britez gave up and went to a

public call center to phone her husband and inform him of the details of her

return trip home.