WUNRN

|

Egypt:

Marriage-Maker's Gender Ruffles Egyptians |

|

5/18/08 |

|

By

Joseph Mayton |

|

Egypt has appointed its first female official to certify marriages and divorces. The move has been met by public debate and opposition from some Muslim clerics who say women shouldn't serve in the role. Seventh in a series on women and Islam. |

|

"I knew it was going to be a little bit in the press, but I didn't really think it would be such a big deal," Soliman says about her February selection by local government officials. "It is what it is and I don't want to have politics as a part of the discussion of me being a maazun because I am a simple housewife who wants to work close to home and raise my kids." Religious leaders have both condemned and endorsed her selection. Her status was significant enough to require the government to approve it. But she's not brandishing it in a quest for equal rights and recoils from having her appointment politicized. "I don't want people, especially the West, to take me as a victory for women in Egypt and the Middle East," she says. "I am Egyptian and a Muslim so what I am doing is for here and not for the West." Already, people know about the "female maazun" in her town of Qaniyat, an hour east of Cairo. "They point you in the direction of 'Madame Soliman's house' if you ask," she says. People knock on her door every day to be married, even though she still waits for official permission to work from the national justice ministry. She has heard about others, though, who will stay away. "Some people have said that I am not appropriate to be a maazun because I am a woman," she says, "but I am confident this will fade with time." Sought

Employment, Not Controversy

Soliman, a 32-year-old mother of three, applied for the position when it became vacant after her father-in-law passed away. The job is not inherited, and there are hundreds of maazuns in Egypt, one for each local district. "I didn't really think about the gender issue when I applied for the job," she says. "It was close to my house and I needed something so close by so I could still be at home for my kids." Ten others, all men, applied to fill the vacancy. Soliman had a master's degree in law from Zagazig University as well as law and criminal justice diplomas and had the highest qualifications. Justice Minister Mamdouh Marei has sought to relieve tensions among Egypt's powerful Islamic scholars, saying that Soliman's nomination was based "on her abilities rather than on her gender." A year ago, 30 women were appointed as judges in response to activists' complaints that Egypt lagged in female participation in the judiciary. "Everyone is beginning to recognize women's rights and women's potential," Hanan Abdel-Aziz, one of the appointed judges, told the state press at the time. Egypt has stood out among Arab nations in women's participation in many aspects of life and politics. Suffrage was granted in 1956, ahead of most others in the region. Women are about 30 percent of the private professional and technical work force, but few are high officials in the government. Detecting Forced

Marriages

One of Soliman's responsibilities will be to ensure there is no coercion behind a wedding, particularly when younger brides are involved. As many as one in three weddings are forced upon the woman, who is often under 18, according to the Egyptian Center for Women's Rights in Cairo. "As a woman I will be better able to find out if the girl wants to get married and if she is being forced into the agreement by an outside party," Soliman says. "I wanted to take this position because it gives women and girls who are getting married a real opportunity to take action." Ibrahim Abdel Salam, 26, an employee at a Cairo cafe, nonetheless objects. "It is wrong to have a woman in this position. My sheikh tells me that if we are to get married that we must avoid her because she can't do the job." "I know that women are not as strong as men," says Heba Mahmoud, a female student at Cairo University who, like many young people here, embraces conservative Islam, which is growing in influence in Egypt. "That is why some jobs are supposed to remain in the hands of men. She can't do the job. I mean, there are so many reasons that she can't, but when it comes down to it, women are not made to be in positions of power." Islamic scholars are divided about a woman having legal responsibility for marriage and divorce. A devout Muslim, Soliman embraces the view that Islam does not bar women from having a career in anything. "Islam is pro-women's rights and it is social customs that put women's rights backward," she says. No Religious

Prohibition

No religious texts ban a female maazun, says Sheikh Fawzi Zefzaf, deputy director of Al-Azhar University, an influential center of Sunni Muslim theology. "But when a woman is menstruating she must not enter a mosque or read Quranic verses and that will affect her job, so for this reason we say it is not advisable to have a woman maazun," the sheikh said in a statement from his office. Soliman says she will conduct home visits with couples who need her authority to avoid breaking Islamic law and an assistant will be able to work in the mosque when she is forbidden to enter. "This is an opportunity for women to show that they have a right to be in such positions and the Arab and Islamic world need to accept this and move forward," says Mohamed Serag, a professor of Islamic studies at the American University in Cairo. The profession used to be "a man's business" and the controversy will pass, Serag says. "She is a public notary, not an official representative of Islam and this needs to be understood." The manner in which some scholars are downgrading the maazun's importance is disconcerting to Aida Seif Al Dawla, a leading activist. She wonders "why was it all over the press" if Soliman's job is inconsequential. "This is a precedent for women in Egypt no matter what anyone says," Seif Al Dawla says. "Since when has getting married not been important? I say good for her for taking this step." Soliman says a female maazun is more likely to be readily accepted in Cairo, where people are "more open" than in her own town. But the time has arrived for women to enter the profession. "I think Egypt is ready for this." |

================================================================

To leave the list, send your request by email to:

wunrn_listserve-request@lists.wunrn.com. Thank you.

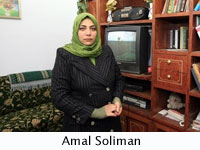

CAIRO,

Egypt (WOMENSENEWS)--Amal Soliman did not realize how large a controversy

would erupt here when she sought to become Egypt's first female

"maazun," or Islamic public notary who performs wedding ceremonies

and authorizes marriage and divorce certificates.

CAIRO,

Egypt (WOMENSENEWS)--Amal Soliman did not realize how large a controversy

would erupt here when she sought to become Egypt's first female

"maazun," or Islamic public notary who performs wedding ceremonies

and authorizes marriage and divorce certificates.