WUNRN

MATRIARCHY & THE MOUNTAIN VII

Centre of Alpine Ecology, December 2007

Trento, Italy

Hilkka Pietilä, M.Sc.

E-mail: hilkka.pietila@pp.inet.fi

THE UNPAID WORK IN HOUSEHOLDS -

A COUNTERFORCE TO MARKET GLOBALIZATION

Introduction

Today, there is a pressing need for a new, more

comprehensive and relevant perception of human economy as a whole in order to

understand the prerequisites for sustainable livelihood for the whole of the

humanity and to be able to create a lifestyle which could provide a dignified

quality of life for all people, with due respect to the ecological boundaries

of the biosphere.

The new perspective is also needed as the counterforce

in the hands of people against the overriding market globalization, which is

intimidating the democratic power, i.e. the traditional channels of people to

influence in their society and economy. We are seeking the people’s power to

control the market and to have their economy in their own hands.

1. The full picture of human economy

The concept of human economy is used in this paper to

signify all work, production, actions and transactions needed to provide for

the livelihood, welfare and survival of people and families, irrespective of

whether they appear in statistics or are counted in monetary terms.

Here we see the human economy as composed of three

major, distinct components, which are the household economy and the cultivation

economy in addition to the industrial economy. In fact, households and

cultivation have always existed, long before money and industry were ever

invented, but they are still invisible in the eyes of mainstream neoliberal economists.

The major blind spots in the prevailing economic

thinking seem to be:

- the household economy, which is used

here for the nonmarket, unpaid work and production in the family or a group of

people having a household together for the management of their daily life or

even a group of small households living close enough to create a joint economic

unit, and

- the cultivation economy, i.e. the

production based on the living potential of nature, which is the interface

between economy and ecology, human culture facing the ecological laws.

Both of these economies are very basic from the point

of view of a sustainable way of living, and thus for human survival and

people's ability to control their own lives.

A particular feature of the households is the extent

and significance of nonmarket work of people without pay for direct production

of human welfare, and thus as an essential contribution to satisfy the basic

needs. A particularity of the cultivation economy is its profoundly unique

nature by being based on potential of living nature. As we know, the human

abilities cannot control and direct the elements of nature; therefore the

humanity should be wise enough for taking the terms of nature seriously into

consideration.

Figure 1.

THE TRIANGLE OF HUMAN

ECONOMY

HOUSEHOLDS

1.

Skills andability

2.

Voluntary work

3.

Care andwellbeing

Graph: Hilkka Pietilä

Households,

Cultivation and Industry and trade are the basic pillars of the human economy.

Each one of these components has different foundations and terms of operations.

This has to be taken into consideration in the agency of human economy in order

to achieve sustainable exchange and collaboration between all three.

In founding of

economics the processes in cultivation and unpaid work and production in the

households have both been left out of the realm of economic science. Therefore

it is obvious that this kind of economics is only a narrow part of human

economy as a whole. However, during these couple of hundred years this narrow

philosophy of economics has become the only theory and language of economists,

by way of which the value of production and work, exchange and spending is

assessed and measured.

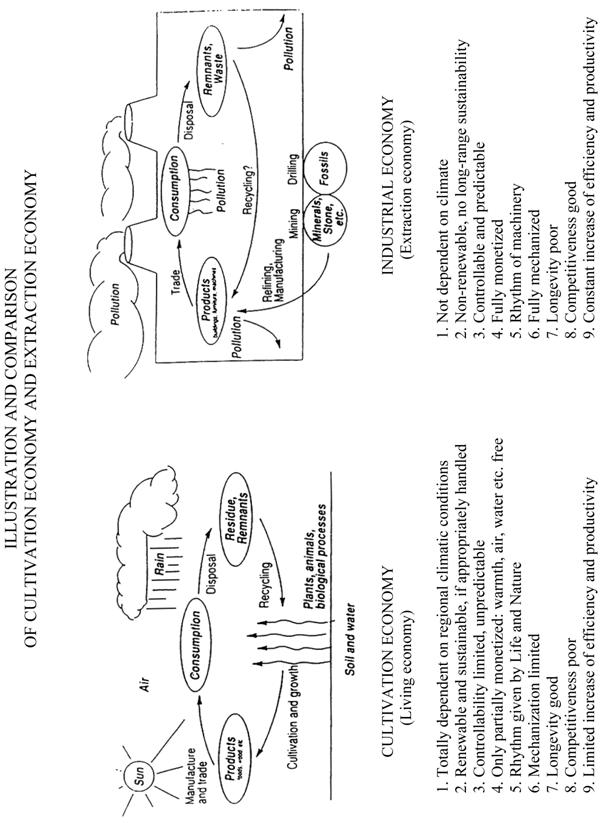

Figure 2.

illustrates the great and essential differences between Cultivation economy and

Industrial economy. The industrial economy can also be called Extraction economy,

since it is based on dead elements extracted from the soil; stone, minerals and

fossil fuels. It also deal only with dead transaction like trade, traffic,

currencies and accounts and its value is measured by money, which is a

nonmaterial fiction.

Figure 2.

2. The historical picture

In human history after the transition from the

gathering economy to the cultivation economy the extended farming family has

been the basic unit of livelihood for long periods. Along the time the people’s

skills and means developed to enable qualitatively better satisfaction of their

basic needs. This kind of “a house-hold” (note: holding the house/farm) was

fairly independent and self-reliant economic unit at the modest level. The

livelihood was based on the quality and accessibility of natural resources and

skills and assiduity of the people living together.

During the course of centuries various kinds of

production and trade, independent artisania, exchange of goods and services,

public institutions and administration were emerging around the farming

families. The public society and economy was in the making. A means of exchange

came into the picture, and people started to buy and sell goods and services.

Figure 3.

The Historical Picture - See

Attached

When the basic functions for

livelihood are performed within families, they cost a lot of time and work, but

when externalized into the public sphere, they will cost money. In this process

many of the traditional vital functions were substituted with commercial ones.

Thus they became dispensable and therefore the status of women as providers was

declining.

A major part of economic

growth in the past centuries has consisted of the functions being transferred

from the private family to the public one, from the non-monetary economy to the

monetary one and thus been made visible and counted. This way the life and

production also has become monetized and commercialized.

From women's

point of view this discussion is very important. The non-monetary economy even

in the industrializing countries has until lately been primarily a female

economy. Its invisibility is a supreme manifestation of women's invisibility in

the society at large. Today the family economy is still primarily in the hands

of women even in its monetized form, the consumption of marketed goods and

services, since the purchasing decisions are made primarily by women.

In the emergence of the public, monetarized

economy, production, politics, culture

and organization outside the private family, all this was designed, planned and

built up exclusively by men, who possessed neither the particular gifts nor the

experience of women acquired over

centuries in the management of the private family and nurturing its members.

A Swedish researcher Ulla Olin, who analyzed this process, was bold enough to conclude

in 1975,

that

the long-term imbalance between male and female rate of influence in planning

and conduct of modern industrial societies is the virtual source of most of

social, economic, human and international problems which we face today.

3. The monetary value of housework

For the statistics the value of work in households can

be calculated in money. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and

Development, OECD, did a lot of work for creating the data sources and methods

for measurement of unpaid, non-market household work and production in the OECD

countries (OECD, 1995). Also the UN Institute INSTRAW has developed these

methods (INSTRAW 1995). It is obvious that the estimates of the value of

household production depend on the method used. (Annex 1.)

In

Table 1. Gender distribution of

unpaid labour in households in Finland

1980 1990 2001

Hours/minutes/day

Women 4.48 3.56 3.47

Men 1.54 2.20 2.27

6.42 6.16

6.14

The distribution of unpaid work between men and women varies

a lot between the families as well as between the countries. But statistically

there is hardly any change taken place between 1990 and 2001.

In these studies in

The monetary value of unpaid work has also been

calculated and the measuring rod has been either the average wages in the

labour market for all employees or the current salary of municipal home

helpers. They give somewhat different figures, but the first one is more

relevant, since the housework requires several skills and competences. When

compared with the GNP of same years the proportions in

Table 2. Value of unpaid work and production in

households in

Hours/minutes/day Mrd

euros % GNP

1980 6.42 13.0 42 %

1990 6.16 39.0 45 %

2001 6.14 62.8 46 %

The percentages given imply that the amount of unpaid

labour in the households would be the highest single contribution into the GNP

if it were counted. In comparison with the state budgets the value of unpaid

work is usually about two times the sum total of the same year’s state budget.

The UNDP/Human Development Report 1995 gives even a

global estimate of the amount of women's unpaid labour. "If more human

activities were seen as market transactions at the prevailing wages, they would

yield gigantically large monetary valuations. A rough order of magnitude comes

to a staggering 16 trillion (dollars) - or (if added, it would make a total of)

about 70 % more than the officially estimated 23 trillion of global output. Of

this 16 trillion, 11 trillion is the non-monetized, invisible contribution of

women."

"Of the total burden of work, women carry on

average 53 % in developing countries and 51% in industrial countries." Out

of the total time of women's work, 1/3 is paid and 2/3 unpaid. For men it is

just the reverse, 3/4 of their working time is paid and only 1/4 is unpaid.

"If women's unpaid work were properly valued, it is quite possible that

women would emerge in most societies as the major breadwinners," concludes

the HD report (UNDP, 1995).

"For the last fifty years national income

statistics have been widely used for monitoring economic developments, for

designing economic and social policies and for evaluating the outcomes of those

policies. Had household production been included in the system of

macro-economic accounts, governments would have had quite a different picture

of economic development and may well have implemented quite different economic

and social policies," concludes the OECD researcher Ann Chadeau, who has done extensive work on this issue (1992).

4. The dogma of the

market versus household-ideology

An Italian economist Mario

Cogoy reminded already in 1995 about the original dogma of industrial

society that economic progress consists of a continual shift of labour and

skills from household-based production to commodity-based consumption. He said

that the extreme form of market utopia

consists of two ideas:

-

on one hand it will aim to the total abolition of work

and skills in the households, in the private life of people, since all labour

and skills are absorbed into the market.

-

on the other hand people are supposed to acquire

professional competence only in one single field, where they will then earn

money enough to buy everything else in life from the market.

The time people spend outside the economic system is

reduced to pure unskilled leisure-time. This way the living households would

cease to exist, the people will become totally dependent on market and the home

remains only as a place to sleep. This would legitimate the continuity of the

market forever, render people market slaves and annihilate the human dignity of

everybody. This is the ultimate ideology of the market (Cogoy 1995).

If market forces are allowed to pursue these aims to

the ultimate, it will imply that people will find themselves helpless and

powerless pawns in their society,

However, the household is still the area of the

economy where people do have power in this world, where they find very few

options to influence macro economic issues. The choice to decide how much one

would like to produce by her/himself and how much to buy from the market is

exactly the leverage of power still in the hands of individuals. It is crucial

to everyone’s own personal independence and integrity in life, whether she/he

keeps this power in her/his own hands or lets it vanish away.

The “ideology” of the households is contrary to the

one of the market. The human being and her wellbeing is the point of departure

for the household, her dignity and integrity are its basic values. According to

the household-ideology all work and production is for people, to serve their

needs and aspirations, physical, mental and spiritual.

We saw above

that households and women have critical position in the human economy, therefore

we can draw the conclusion, that they also could turn the trend. They can

change the values and lifestyle in families back to the basics, less consumption

of the market goods and services, more emphases on commonality, working

together, making family life self-servicing, achieving pleasure and satisfaction

by being and doing instead of buying and paying.

In this school of thinking the purpose of all labour

and production in human societies should serve human needs and purposes. There

would not be other purpose for the production and trade, and no other

legitimacy. According to this thinking

every

individual is indispensable and dignified member of the family and community,

and we are all subjects in our own life, not objects of anonymous market

forces.

5. Turning the trap into an asset - the Utopia for

good life?

We should turn

present trap of shrinking role of the households to an asset. In the early

1980s the founder of futurology, Robert Jungk, made the point that “people

out of work are, in certain way, in a privileged position because they are no

longer chained to the capitalist production machine. They have more time, they

can think and act in ways which may be beneficial for society, if they only

have enough motivation.” (Jungk, 1983)

At that time Robert

Jungk referred to the unemployed people being more or less permanently without

paid jobs. Today we may apply this thought also to the people who have paid job

only temporarily or occasionally. These people are in the trap of constant

job-seeking and they find themselves forced to accept almost any kind of work

on any salary.

However, the thought

of Robert Jungk gives some hope that we could – and we should – stop the rat

race and turn around the wheel. We should not let the lack of a regular job to

render us paralyzed and hopeless. We can realize that this situation will allow

us to command more of our time, and the scarce income could become an incentive

for us to make more use of our skills, knowledge and experience in our own

households. These thoughts could be a hint for finding one’s own creativity and

initiative. While finding her/his own skills for helping oneself will lead

better control of one’s own life, too!

How would it feel

like, if we make our own plans for our household economy and decide to do more

at home in order to decrease our dependence on the money-income and supply of

the markets? Then we will realize

that the more of necessary goods and services we are able to produce by

ourselves, the less we are dependent on the market, both on labour market and

the market of goods and services.

Would this become a

strategy to use power from below to influence the economy around us, too? This kind of an economic transition will make the

household again an asset in the hands of people. A decisive prerequisite for

making these changes possible is the multiplicity of practical skills, which we

can acquire for instance from elderly relatives, the advisory books or various

training lessons and courses – if we have never learned them or forgotten them.

However, we should

not allow this change to increase the workload of women in the house again.

Therefore it is necessary to equalize the distribution of labour between women

and men, girls and boys, at home. Even for the sake of men themselves it would

be necessary to design a new division of labour in the house. When men can no

longer be the single breadwinners anyway, they could become direct supporters

of their families in practice and it will give them a meaningful and rewarding

new role in the family. Within the younger families in the Nordic countries we

already have good signs of this kind of transition.

The richer the family is in the practical skills of

its members, the better chances they have together to decide their

relationships- if it were counted. Together with the monetary contribution of

households as consumer units these contributions make an enormous “hidden

market force” or potential leverage of power in our hands. It is real people’s

power from below over the neoliberal macro economy globally.

Today the globalized capitalist market forces have

become a new “totalitarian super power”, which has rendered our democratically

elected governments and political institutions fairly powerless. And the more

representative democracy is intimidated, the more we need a new kind of

people’s power from below.

To summarize I would like conclude that as individuals

we can reassume our right to decide ourselves, how much of our work, time,

skills and know-how we are willing to sell to the labour market and how much goods and services we are

willing to buy from the commodity market.

This would be the way to regulate our degree of dependence on the market. The

pivotal assets are skills and money, but the skills are more important than

money.

After all, the entire

picture of the human economy should be turned the right side up;

the industrial and commercial

economy should be seen only as auxiliary, serving the needs of families

and individuals instead of using them as means of production and consumption.

This turn around of

the economy will never be made by the market, nor by our democratic governments

any more in today’s world. In the globalizing world we have to do it by

ourselves, to take the power back in our own hands to command our own

lives. For that purpose we have to

denounce the values and rules on which the neoliberal economy operates, such as

constant economic growth, conspicuous consumption, maximization of

profits and competition by

everybody against everybody in everything and everywhere.

If we stop obeying the signals of marketing,

advertising, fachions of all kinds etc. the expansion of the market will stop.

We can stop consuming more than we need. We can start saving instead of

consuming - not only money but the climate, natural resources, goods, our time

etc.

We can cooperate and serve others instead of

competing, Not to believe, obey and go

along with the market will be the end of market-slavery and the beginning of

our new liberation.

The really powerful choice is to buy or

not to buy - to reject all advertising, fashions, marketing and other

manipulation and decide independently by ourselves, what we need and what we

don’t need.

People’s power is

always acts of individuals, democracy is the power of millions of individuals

acting together in the society at large. This will be the democracy in the age

of globalized market hegemony. with both the labour and commodity markets. And

the richer the village, community or local cooperative is in skilful and

multitalented people, the less dependent they are on the goods and services

provided by the market. Furthermore, gaining more control on their own economy

they will also gain insight to influence the economy of their society.

6. Democracy

in the age of globalizing power?

We saw above that the sum total of the unpaid production of goods and services in the families does constitute the biggest single contribution to the national GNP in each country

- if it were counted. Together with the monetary

contribution of households as consumer units these contributions make an

enormous “hidden market force” or potential leverage of power in our hands. It

is real people’s power from below over the neoliberal macro economy globally.

Today the globalized capitalist market forces have

become a new “totalitarian super power”, which has rendered our democratically

elected governments and political institutions fairly powerless. And the more

representative democracy is intimidated, the more we need a new kind of

people’s power from below.

To summarize I would like conclude that as individuals

we can reassume our right to decide ourselves, how much of our work, time,

skills and know-how we are willing to sell to the labour market and how much goods and services we are

willing to buy from the commodity

market. This would be the way to regulate our degree of dependence on the

market. The pivotal assets are skills and money, but the skills are more

important than money.

After all, the entire

picture of the human economy should be turned the right side up;

the industrial and commercial

economy should be seen only as auxiliary, serving the needs of families

and individuals instead of using them as means of production and consumption.

This turn around of

the economy will never be made by the market, nor by our democratic governments

any more in today’s world. In the globalizing world we have to do it by

ourselves, to take the power back in our own hands to command our own

lives. For that purpose we have to

denounce the values and rules on which the neoliberal economy operates, such as

constant economic growth, conspicuous consumption, maximization of

profits and competition by

everybody against everybody in everything and everywhere.

If we stop obeying the signals of marketing,

advertising, fachions of all kinds etc. the expansion of the market will stop.

We can stop consuming more than we need. We can start saving instead of

consuming - not only money but the climate, natural resources, goods, our time

etc.

We can cooperate and serve others instead of

competing, Not to believe, obey and go

along with the market will be the end of market-slavery and the beginning of

our new liberation.

The really powerful choice is to buy or

not to buy - to reject all advertising, fashions, marketing and other

manipulation and decide independently by ourselves, what we need and what we don’t

need.

People’s power is always acts of individuals, democracy is the power of millions of individuals acting together in the society at large. This will be the democracy in the age of globalized market hegemony.

Annex

1.

Hilkka

Pietilä,

Excerpt of

a long paper.

THE METHODS OF CALCULATING THE TIME AND VALUE

OF UNPAID WORK IN THE HOUSEHOLDS

The Organization for Economic

Cooperation and Development, OECD has collected a lot of data of the sources

and methods for measurement of unpaid, non-market household work and production

in the OECD countries (OECD, 1995). These main categories of methods are based

on time use surveys as the base line data. Then the value of time is calculated

according the following methods:

- the

“opportunity cost” method is based on the potential salary, what is the

wage opportunity lost by the one who does unwaged work, for example caring for her

children or parents or doing subsistence farming instead of doing a paid job;

- the "global substitute"

method, whereby a general housekeeper's wage rate on the market is taken as a

substitute value for all unpaid housework, which rests on the assumption that

housework does not require any particular qualifications. Therefore also the

average wage in the labour market is used within this method.

- the

"specialist substitute" (also called “the replacement cost”)

method, which relates various types of household tasks to the wage levels for

the type of work performed by professionals such as cooks, nurses, gardeners

etc.

All these

ways of measurement are applying the so called input-based method,

because they measure the household production through the inputs to the process

as the working hours.

The UN

International Research and Training Institute for the Advancement of Women,

INSTRAW, suggests also an output-based method:

-

the “output-based evaluation” implies the valuation of the

non-market production in terms of the market value of the outputs produced,

whereby the products and services produced in the household are assigned a

value equivalent to the price of similar market goods and services (such as the

meals served in the restaurant, the cleaning performed by a professional firm,

etc).

Output-based evaluation method does not require time-use data, but data

about the amount of goods and services produced in the households and their

values in the market.

References:

Chadeau,

Ann. (1992). What is Households' Non-market

Production Worth? OECD Economic Studies No.18, Spring 1992.

Cogoy,

Mario. (1995). “Market and non-market determinants of private consumption and .their

impacts on the environment”. Ecological

Economics 13 (1995) 169-180.

EUROSTAT,

Statistical Office of the European Communities. (1998). Proposal for a Satellite Account of Household Production. DOC E2/TUS/4/98.

Housework Study. (1981). Part 8. Official Statistics of

INSTRAW.

(1995). Measurement and valuation of unpaid

contribution: accounting through time and output.

Jungk,

Robert. (1983). Under Conditions of Humanquake. An interview in IFDA Dossier

34, March/April 1983.

OECD. (1995). Household Production in OECD Countries. Data

Sources and Measurement Methods.

Olin, Ulla.

(1975). “A case for Women as

Co-managers. The Family as a General Model of Human Social Organization and its

Implications for Women's Role in Public Life.” In: Tinker, Irene and Bo

Bramsen, Michele (Eds.), Women and World

Development.

Pietilä, Hilkka.

(1990 b). “The

Daughters of Earth: Women's culture as a basis for sustainable development”.

In: Engel, J.R. & Gibb Engel, Joan (ed.): Ethics of Environment and Development. London/Belhaven Press.

Pietilä,

Hilkka. (1997). “The triangle of the

human economy: household - cultivation - industrial production. An attempt at

making visible the human economy in toto.” Ecological

Economics, The Journal of the International Society for Ecological

Economics, 20 No 2 (1997) 113-127.

System

of National Accounts, 1993. EUROSTAT, IMF, OECD, UN, World

Bank.

UNDP.

(1995). Human Development Report, 1995.

United

Nations. (1996). Platform for Action and the

Varjonen,

Johanna – Aalto, Kristiina. Household

Production and Consumption in Finland 2001. Household Satellite Account,

Statistics

================================================================

To leave the list, send your request by email to:

wunrn_listserve-request@lists.wunrn.com. Thank you.