WUNRN

The

holiday of Halloween, October 31, is often a time of reference to WITCHES and

historical abuse and even killing of women accused of being WITCHES and

practicing WITCHCRAFT.

To

show the violence and abuse of women allegedly accused of being

WITCHES, historically in Europe and in the US, WUNRN will post two

releases on WITCHES. Tragically, some vestiges of Witch Hunts and Killings have

also occurred in more modern times, and in other parts of the world.

The

UN Study focus of WUNRN, considered the ONLY UN official Study on the Status of

Women and Freedom of Religion or Belief and Traditions, includes

reference to the term "witches" and their inhumane treatment in:

D.Prejudices

to the Right to Life

152.

Cruelty to Widows

153."Religions

are not the only value system which can lead to killing of "witches"

or to deaths of 200 women in India each year, usually widows with property or

undesired pregnancies."

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Case Study:

The European Witch-Hunts, c. 1450-1750

and Witch-Hunts Today

Summary

For three centuries of early modern European history, diverse societies were consumed by a panic over alleged witches in their midst. Witch-hunts, especially in Central Europe, resulted in the trial, torture, and execution of tens of thousands of victims, about three-quarters of whom were women. Arguably, neither before nor since have adult European women been selectively targeted for such largescale atrocities.

The background

The witch-hunts of early modern Europe took place against a backdrop of rapid social, economic, and religious transformation. As we will see in the modern-day case-studies below, such generalized stress -- including the prevalence of epidemics and natural disasters -- is nearly always central to outbreaks of mass hysteria of this type. Jenny Gibbons' analysis ties the witch-hunts to other "panics" in early modern Europe:

Traditional [tolerant] attitudes towards witchcraft began to change in the 14th century, at the very end of the Middle Ages. ... Early 14th century central Europe was seized by a series of rumor-panics. Some malign conspiracy (Jews and lepers, Moslems, or Jews and witches) was attempting to destroy the Christian kingdoms through magick and poison. After the terrible devastation caused by the Black Death [bubonic plague] (1347-1349), these rumors increased in intensity and focused primarily on witches and "plague-spreaders." Witchcraft cases increased slowly but steadily from the 14th-15th century. The first mass trials appeared in the 15th century. At the beginning of the 16th century, as the first shock-waves from the Reformation hit, the number of witch trials actually dropped. Then, around 1550, the persecution skyrocketed. What we think of as "the Burning Times" -- the crazes, panics, and mass hysteria -- largely occurred in one century, from 1550-1650. In the 17th century, the Great Hunt passed nearly as suddenly as it had arisen. Trials dropped sharply after 1650 and disappeared completely by the end of the 18th century. (Gibbons, "Recent Developments in the Study of the Great European Witch Hunt".)

Gibbons' allusion to the Reformation reminds us that the clash between institutional Catholicism and emergent Protestantism contributed to the collapse of a stable world-view, which eventually led to panic and hyper-suspiciousness on the part of Catholic and Protestant authorities alike. Writes Nachman Ben-Yehuda, "This helps us understand why only the most rapidly developing countries, where the Catholic church was weakest, experienced a virulent witch craze (i.e., Germany, France, Switzerland). Where the Catholic church was strong (Spain, Italy, Portugal) hardly any witch craze occurred ... the Reformation was definitely the first time that the church had to cope with a large-scale threat to its very existence and legitimacy." But Ben-Yehuda adds that "Protestants persecuted witches with almost the same zeal as the Catholics ... Protestants and Catholics alike felt threatened." It is notable that the witch-hunts lost most of their momentum with the end of the Thirty Years War (Peace of Westphalia, 1648), which "gave official recognition and legitimacy to religious pluralism." (Ben-Yehuda, "The European Witch Craze of the 14th to 17th Centuries: A Sociologist's Perspective," American Journal of Sociology, 86: 1 [July 1980], pp. 15, 23.)

The gendercide

The witch-hunts waxed and waned for nearly three centuries, with great variations in time and space. "The rate of witch hunting varied dramatically throughout Europe, ranging from a high of 26,000 deaths in Germany to a low of 4 in Ireland." (Gibbons, Recent Developments.)

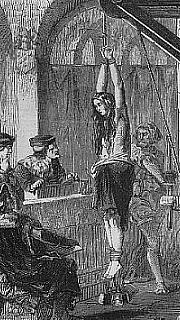

Despite the

involvement of church authorities, "The vast majority of witches were

condemned by secular courts," with local courts especially noted for their

persecutory zeal (Gibbons, Recent Developments). The standard procedure in most

countries was for accused witches to be brought before investigating tribunals

and interrogated. In some parts of Europe (e.g., England), torture was rarely

used; but where the witch-hunts were most intensive, it was a standard feature

of the interrogations. Obviously, a large majority of accused who

"confessed" to witchcraft did so as a result of the brutal tortures

to which they were exposed. About half of all convicted witches were given sentences

short of execution. The unluckier half were generally killed in public, often en

masse, by hanging or burning.

Despite the

involvement of church authorities, "The vast majority of witches were

condemned by secular courts," with local courts especially noted for their

persecutory zeal (Gibbons, Recent Developments). The standard procedure in most

countries was for accused witches to be brought before investigating tribunals

and interrogated. In some parts of Europe (e.g., England), torture was rarely

used; but where the witch-hunts were most intensive, it was a standard feature

of the interrogations. Obviously, a large majority of accused who

"confessed" to witchcraft did so as a result of the brutal tortures

to which they were exposed. About half of all convicted witches were given sentences

short of execution. The unluckier half were generally killed in public, often en

masse, by hanging or burning.

Being female hardly guaranteed that one would be suspected or accused of witchcraft. As Steven Katz notes, "statistical evidence ... makes clear that over 99.9-plus percent of all women who lived during the three centuries of the witch craze were not harmed directly by the police arm of either the state or the church, though both had the power to do so had the elites that controlled them so desired." (Katz, The Holocaust in Historical Context, Vol. I, p. 503.) Nor were all accused witches female. Nonetheless, the witch-hunts can be viewed as a case of "genderized mass murder," according to Katz (p. 503). He adds: "the overall evidence makes plain that the growth -- the panic -- in the witch craze was inseparable from the stigmatization of women. ... Historically, the most salient manifestation of the unreserved belief in female power and female evil is evidenced in the tight, recurrent, by-now nearly instinctive association of women and witchcraft. Though there were male witches, when the witch craze accelerated and became a mass phenomenon after 1500 its main targets, its main victims, were female witches. Indeed, one strongly suspects that the development of witch-hunting into a mass hysteria only became possible when directed primarily at women." (The Holocaust in Historical Context, Vol. I, p. 433 [n. 1], 436.) Katz draws out the depths of this misogyny through a comparison with anti-semitism:

The medieval conception of women shares much with the corresponding medieval conception of Jews. In both cases, a perennial attribution of secret, bountiful, malicious "power," is made. Women are anathematized and cast as witches because of the enduring grotesque fears they generate in respect of their putative abilities to control men and thereby coerce, for their own ends, male-dominated Christian society. Whatever the social and psychological determinants operative in this abiding obsession, there can be no denying the consequential reality of such anxiety in medieval Christendom. Linked to theological traditions of Eve and Lilith, women are perceived as embodiments of inexhaustible negativity. Though not quite quasi-literal incarnations of the Devil as were Jews, women are, rather, their ontological "first cousins" who, like the Jews, emerge from the "left" or sinister side of being. (Katz, The Holocaust in Historical Context, Vol. I, p. 435.)

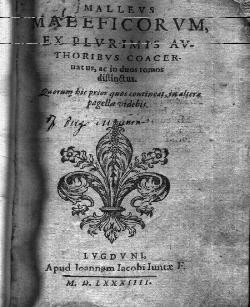

Manuscript

of the Malleus

maleficarum, "the most

influential and widely used handbook on witchcraft."

The classic evocation of this deranged misogyny is the Malleus

maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches), published by Catholic inquisition

authorities in 1485-86. "All wickedness," write the authors, "is

but little to the wickedness of a woman. ... What else is woman but a foe to

friendship, an unescapable punishment, a necessary evil, a natural temptation,

a desirable calamity, domestic danger, a delectable detriment, an evil nature,

painted with fair colours. ... Women are by nature instruments of Satan -- they

are by nature carnal, a structural defect rooted in the original

creation." (Quoted in Katz, The Holocaust in Historical Context, Vol. I,

pp. 438-39.) "The importance of the Malleus cannot be overstated,"

argues Ben-Yehuda:

The classic evocation of this deranged misogyny is the Malleus

maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches), published by Catholic inquisition

authorities in 1485-86. "All wickedness," write the authors, "is

but little to the wickedness of a woman. ... What else is woman but a foe to

friendship, an unescapable punishment, a necessary evil, a natural temptation,

a desirable calamity, domestic danger, a delectable detriment, an evil nature,

painted with fair colours. ... Women are by nature instruments of Satan -- they

are by nature carnal, a structural defect rooted in the original

creation." (Quoted in Katz, The Holocaust in Historical Context, Vol. I,

pp. 438-39.) "The importance of the Malleus cannot be overstated,"

argues Ben-Yehuda:

It was to become the most influential and widely used handbook on witchcraft. ... Its enormous influence was practically guaranteed, owing not only to its authoritative appearance but also to its extremely wide distribution. It was one of the first books to be printed on the recently invented printing press and appeared in no fewer than 20 editions. ... The moral backing had been provided for a horrible, endless march of suffering, torture, and human disgrace inflicted on thousands of women. (Ben-Yehuda, "The European Witch Craze," p. 11.)

An elderly

witch is depicted feeding her satanic "familiars" (woodcut, 1579).

Many scholars have

argued that it was the women who seemed most independent from patriarchal norms

-- especially elderly ones living outside the parameters of the patriarchal

family -- who were most vulnerable to accusations of witchcraft. "The

limited data we have regarding the age of witches ... shows a solid majority of

witches were older than 50, which in the early modern period was considered to

be a much more advanced age than today." (Brian P. Levack, The

Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe, p. 129.) "The reason for this

strong correlation seems clear," writes Katz: "these women,

particularly older women who had never given birth and now were beyond giving

birth, comprised the female group most difficult to assimilate, to comprehend,

within the regulative late medieval social matrix, organized, as it was, around

the family unit." (The Holocaust in Historical Context, Vol. I, pp.

468-69.) As more women than men tended to survive into a dependent old age,

they could also be seen disproportionately as a burden by neighbors: "The

woman who was labeled a witch wanted things for herself or her household from

her neighbors, but she had little to offer in return to those who were not much

better off than she. Increasingly resented as an economic burden, she was also

perceived by her neighbors to be the locus of a dangerous envy and verbal

violence." (Deborah Willis, Malevolent Nurture: Witch-Hunting and

Maternal Power in Early Modern England, p. 65.)

Many scholars have

argued that it was the women who seemed most independent from patriarchal norms

-- especially elderly ones living outside the parameters of the patriarchal

family -- who were most vulnerable to accusations of witchcraft. "The

limited data we have regarding the age of witches ... shows a solid majority of

witches were older than 50, which in the early modern period was considered to

be a much more advanced age than today." (Brian P. Levack, The

Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe, p. 129.) "The reason for this

strong correlation seems clear," writes Katz: "these women,

particularly older women who had never given birth and now were beyond giving

birth, comprised the female group most difficult to assimilate, to comprehend,

within the regulative late medieval social matrix, organized, as it was, around

the family unit." (The Holocaust in Historical Context, Vol. I, pp.

468-69.) As more women than men tended to survive into a dependent old age,

they could also be seen disproportionately as a burden by neighbors: "The

woman who was labeled a witch wanted things for herself or her household from

her neighbors, but she had little to offer in return to those who were not much

better off than she. Increasingly resented as an economic burden, she was also

perceived by her neighbors to be the locus of a dangerous envy and verbal

violence." (Deborah Willis, Malevolent Nurture: Witch-Hunting and

Maternal Power in Early Modern England, p. 65.)

One theory, popularized by Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English in their 1973 pamphlet Witches, Midwives, and Nurses, proposed that midwives were especially likely to be targeted in the witch-hunts. This assertion has been decisively refuted by subsequent research, which has established the opposite: that "being a licensed midwife actually decreased a woman's chances of being charged" and "midwives were more likely to be found helping witch-hunters" than being victimized by them. (Gibbons, Recent Developments; Diane Purkiss, The Witch in History.)

Condemned

female witches are burned at the stake.

Overall,

approximately 75 to 80 percent of those accused and convicted of witchcraft in

early modern Europe were female. Accordingly, Christina Larner's

"identification of the relationship of witch-hunting to

woman-hunting" seems well-grounded, as does her conclusion that the

witch-hunts were "sex-related" if not "sex-specific."

"This does not mean that simple overt sex war is treated as a satisfactory

explanation for witch-hunting, or that the ... men who were accused are not to

be taken into account." Rather, "it means that the fact that the

accused were overwhelmingly female should form a major part of any

analysis." (Larner, Enemies of God: The Witch-Hunt in Scotland, p.

3.)

Overall,

approximately 75 to 80 percent of those accused and convicted of witchcraft in

early modern Europe were female. Accordingly, Christina Larner's

"identification of the relationship of witch-hunting to

woman-hunting" seems well-grounded, as does her conclusion that the

witch-hunts were "sex-related" if not "sex-specific."

"This does not mean that simple overt sex war is treated as a satisfactory

explanation for witch-hunting, or that the ... men who were accused are not to

be taken into account." Rather, "it means that the fact that the

accused were overwhelmingly female should form a major part of any

analysis." (Larner, Enemies of God: The Witch-Hunt in Scotland, p.

3.)

Male

"witches"

Male

"witches"

Robin Briggs

calculates that 20 to 25 percent of Europeans executed for witchcraft between

the 14th and 17th centuries were male. Regional variations are again notable.

France was "a fascinating exception to the wider pattern, for over much of

the country witchcraft seems to have had no obvious link with gender at all. Of

nearly 1,300 witches whose cases went to the parlement of Paris on

appeal, just over half were men. ... The great majority of the men accused were

poor peasants and artisans, a fairly representative sample of the ordinary

population." Briggs adds:

There are some extreme cases in peripheral regions of Europe, with men accounting for 90 percent of the accused in Iceland, 60 percent in Estonia and nearly 50 per cent in Finland. On the other hand, there are regions where 90 per cent or more of known witches were women; these include Hungary, Denmark and England. The fact that many recent writers on the subject have relied on English and north American evidence has probably encouraged an error of perspective here, with the overwhelming predominance of female suspects in these areas (also characterized by low rates of persecution) being assumed to be typical. Nor is it the case that the courts treated male suspects more favourably; the conviction rates are usually much the same for both sexes. (Briggs, Witches & Neighbours: The Social and Cultural Context of European Witchcraft, pp. 260-61.)

How many

died?

"The

most dramatic [recent] changes in our vision of the Great Hunt [have] centered

on the death toll," notes Jenny Gibbons. She points out that estimates

made prior to the mid-1970s, when detailed research into trial records began,

"were almost 100% pure speculation." (Gibbons, Recent Developments.)

"On the wilder shores of the feminist and witch-cult movements,"

writes Robin Briggs, "a potent myth has become established, to the effect

that 9 million women were burned as witches in Europe; gendercide rather than

genocide. [See, e.g., the witch-hunt documentary "The

Burning Times".] This is an overestimate by a factor of up to 200, for

the most reasonable modern estimates suggest perhaps 100,000 trials between

1450 and 1750, with something between 40,000 and 50,000 executions, of which 20

to 25 per cent were men." Briggs adds that "these figures are

chilling enough, but they have to be set in the context of what was probably

the harshest period of capital punishments

in European history." (Briggs, Witches & Neighbours, p. 8.)

Brian

Levack's book The Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe arrives at roughly

similar conclusions. Levack "surveyed regional studies and found that

there were approximately 110,000 witch trials. Levack focused on recorded

trials, not executions, because in many cases we have evidence that a trial

occurred but no indication of its outcomes. On average, 48% of trials ended in

an execution, [and] therefore he estimated 60,000 witches died. This is

slightly higher than 48% to reflect the fact that Germany, the center of the

persecution, killed more than 48% of its witches." (Gibbons, Recent Developments.)

Nonetheless,

in the view of Gendercide Watch, even such a reduced and diffused death-toll

should be considered "gendercidal," in that it inflicted mass

gender-selective killing on European women. Such killing does not need to be

totalizing, either in its ambitions or its impact, to meet the definitions of

gendercide and genocide that we use. Indeed, it is arguable that at no other

time in European history have adult women been targeted selectively, on

such a scale, for torture and annihilation.

Who was

responsible?

The medieval

witch-hunts have long been depicted as part of a "war against women"

conducted exclusively or overwhelmingly by men, especially those in positions

of central authority. Deborah Willis notes that "more polemical"

feminist accounts "are likely to portray the witch as a heroic

protofeminist resisting patriarchal oppression and a wholly innocent victim of

a male-authored reign of terror designed to keep women in their place."

(Willis, Malevolent Nurture, p. 12.)

In fact, the

stigmatizing, victimizing, and murdering of accused "witches" is more

accurately seen as a collaborative enterprise between men and women at the

local level. "The historical record suggests that both men and women found

it easiest to fix these fantasies [of witchcraft], and turn them into horrible

reality, when they were attached to women. It is really crucial to understand

that misogyny in this sense was not reserved to men alone, but could be just as

intense among women." Most of the accusations originated in

"conflicts [that] normally opposed one woman to another, with men liable

to become involved only at a later stage as ancillaries to the original

dispute." Briggs adds that "most informal accusations were made by

women against other women, ... [and only] leaked slowly across to the men who

controlled the political structures of local society." At the trial level,

his research on the French province of Lorraine found that

women did testify in large numbers against other women, making up 43 per cent of witnesses in these cases on average, and predominating in 30 per cent of them. ... A more sophisticated count for the English Home Circuit by Clive Holmes shows that the proportion of women witnesses rose from around 38 per cent in the last years of Queen Elizabeth to 53 per cent after the Restoration. ... It appears that women were active in building up reputations by gossip, deploying counter-magic and accusing suspects; crystallization into formal prosecution, however, needed the intervention of men, preferably of fairly high status in the community." (Briggs, Witches & Neighbours, pp. 264-65, 270, 273, 282.)

Deborah

Willis's study of "Witch-Hunting and Maternal Power in Early Modern

England" similarly finds it "clear ... that women were actively

involved in making witchcraft accusations against their female

neighbours":

[Alan] Macfarlane finds that as many women as men informed against witches in the 291 Essex cases he studied; about 55 percent of those who believed they had been bewitched were female. The number of witchcraft quarrels that began between women may actually have been higher; in some cases, it appears that the husband as "head of household" came forward to make statements on behalf of his wife, although the central quarrel had taken place between her and another woman. ... It may, then, be misleading to equate "informants" with "accusers": the person who gave a statement to authorities was not necessarily the person directly quarreling with the witch. Other studies support a figure in the range of 60 percent. In Peter Rushton's examination of slander cases in the Durham church courts, women took action against other women who had labeled them witches in 61 percent of the cases. ... J.A. Sharpe also notes the prevalence of women as accusers in seventeenth-century Yorkshire cases, concluding that "on a village level witchcraft seems to have been something peculiarly enmeshed in women's quarrels." To a considerable extent, then, village-level witch-hunting was women's work. (Willis, Malevolent Nurture, pp. 35-36.)

These

comments and data serve as a reminder that gendercide against women may be

initiated and perpetrated, substantially or predominantly, by "other

women," just as gendercide against men is carried out overwhelmingly by

"other men." The case of female infanticide

can also be cited in this regard. Patriarchal power, however, was ubiquitous at

all later stages of witchcraft proceedings. Men were exclusively the

prosecutors, judges, jailers, and executioners -- of women and men alike -- in

Europe's emerging modern legal system.

Witch-hunts

today

Few people

are aware that witch-hunts still claim thousands of lives every year,

especially in the countries of sub-Saharan Africa, and above all in South

Africa.

Witch-hunts

in South Africa have become "a national scourge," according to

Phumele Ntombele-Nzimande of the country's Commission on Gender Equality.

(Quoted in Gilbert Lewthwaite, "South Africans go on witch hunts," Baltimore

Sun, September 27, 1998.) The phenomenon is centered in the country's

poverty-stricken Northern Province, where "legislators counted 204

witchcraft-related killings [from 1985-95] ... Police counted 312 for the same

period. Everybody agreed both numbers were gross underestimates." (Neely

Tucker, "Season of the Witch Haunts Africa," The Toronto Star,

August 1, 1999.) In 1996 The Observer (UK) reported that "the

precise statistics are not known, but the deaths from witch-burning episodes

number in the hundreds each year and the trend appears to be on the rise."

(David Beresford, "Ancient superstitions, fear of witches cast spell on

new nation," reprinted in The Ottawa Citizen, June 18, 1996.)

As with its

European predecessor, witch-hunting in South Africa is closely tied not only to

prevailing superstitions, but to socio-economic pressures, natural disasters,

and personal jealousies. In the Northern Province, "among the poorly

educated rural residents, traditional healers and clairvoyants claiming

supernatural powers hold broad sway. And hunger, poverty, and unemployment can

create jealousies that can quickly turn to anger and vengeance."

(Lewthwaite, "South Africans go on witch hunts.") Likewise, Peter

Alexander reports that "In a region of intense poverty and little

education, villagers are quick to blame any adverse act of fate on black

magic." These traditional tendencies have been exacerbated by a recent

hysteria (extending to Kenya and Zimbabwe) over the very real phenomenon of

"ritual killings related to witchcraft," which "include the

removal of organs and limbs from the victims -- the genitals, hands or the

head, all of which are believed to bring good luck." (Alexander,

"'Witches' get protection from superstitious mobs," The Daily

Telegraph, May 26, 1997.) Such ritual murders often bring

"retribution" against innocents accused of witchcraft.

The

intensity of the persecution and vigilantism in South Africa has reached such

levels that no fewer than ten villages have been established in the

Northern Province, populated exclusively by accused "witches" whose

lives are at risk in their home communities. One such settlement, Helena,

counted among its residents 62-year-old Esther Rasesemola, who "was

accused in 1990 of being a witch after lightning struck her village":

A group of people visited the Inkanga [village witch-doctor] to see who was responsible. When they returned, it was my brother-in-law who told the rest of the village that I was responsible. He owed me money and I think he did it to get rid of me because he did not want to pay the money back. People in the village became convinced I was a witch. They came to my house at night and burnt it down and took all my belongings. Then they put me in a truck and drove me to a deserted place and dropped me off with my husband and my three children. They told me never to come back to the village or they would kill me. My husband died two years after we were expelled. My children have gone away and now I have nothing. I don't believe in witchcraft. It is just superstitious belief. (Quoted in Alexander, "'Witches' get protection.")

Gilbert

Lewthwaite of the Baltimore Sun described the case of Violet Dangale, a

42-year-old woman who "was driven from her home 30 months ago by relatives

and neighbours who accused her of being a witch growing rich from the work of

zombies, as the 'living dead' are known." Now she was "penniless and

in fear for her life," living in Tshilamba, another of the refuges for

accused witches. Her "main accuser was her uncle. He first accused her

father of using zombies to enrich himself. Then he turned on her, suggesting

that she enjoyed her share of the family's wealth through witchcraft. ... As

the accusations and threats grew stronger, the Dangale family fled their homes

in Dzimauli." "They said I was a witch," Dangale told

Lewthwaite. "I don't know anything about witchcraft. I don't believe in

zombies. Since I was born, I never saw a zombie." (Lewthwaite, "South

Africans go on witch hunts.")

Both of

these women were luckier than 65-year-old Linah Seabi, "a sorghum beer

brewer ... [who] was charged with killing an elderly woman with a poisonous

potion. More than 200 villagers stormed Seabi's house in late May [1991], beat

her and burned her to death with straw thatch from the roof of her house."

(Nina Shapiro, "Wave of witch hunts sweeps South African

countryside," The Toronto Star, September 19, 1991.) In December

1998, "Francina Sebatsana, 75, and Desia Mamafa, 55 ... were burned to

death on pyres of wood in the village of Wydhoek," in the Northern

Province, for alleged witchcraft. "Eleven men, ages 21 to 50" were

charged with her murder. (Lewthwaite, "South Africans go on witch

hunts.")

The

gendering of the European witch-hunts appears to be closely duplicated in the

South African case. As the above accounts suggest, "traditionally, it is

women who are accused of witchcraft" (Alexander, "'Witches' get

police protection"). Especially vulnerable are "defenceless elderly

women, against whom the actions are taken without resistance," according

to Northern Province Premier Ngoako Ramatlhodi. "That women most often are

the victims of witch hunts stems from attitudes toward gender," writes

Nina Shapiro of The Toronto Star:

"In our culture, men go out in the afternoon, women remain in the home," said Russell Molefe, a local journalist. People believe women sit at home concocting potions, he said. Older women are suspected, according to Lebowa police lieutenant Mohlabi Tlomatsana, simply because they are alive. "People will think 'Why has she not died? Probably because she is a witch.'" (Shapiro, "Wave of witch hunts.")

However, as

in the European case-study, "these days almost a third of victims of

men" (Alexander, "'Witches' get police protection.")

Nonetheless, approximately 30 percent of accused witches are male -- reflecting

men's prominence as nangas, or traditional healers. Anton La Guardia

describes the case of "Credo Mutwa, southern Africa's best-known

practising healer ... [who] said he had been accosted by a mob and stabbed

several times. He lay bleeding on the ground and waited helplessly to die as

his assailants poured petrol and prepared to set it alight. Mr. Mutwa ... said

he was saved by the same superstition which was about to claim his life. 'A

young man shouted, "His ghost will haunt you." They vanished, leaving

me like a fish on dry land.'" (La Guardia, "South Africa's

non-political witch-hunts," The Daily Telegraph, September 9,

1998.)

As in all

these campaigns, it is difficult to assign particular responsibility for

fuelling the anti-witch hysteria. Although they may themselves be accused of

witchcraft, it is also generally the nangas who are called upon to point

out "suspicious" persons who can be accused as witches: according to

one South African police sergeant, "Generally, if people believe there is

a witch in their village, they will consult the [witch-doctor]. He or she will

then 'sniff out' the witch. The person who is accused will then be killed or

ordered to leave the village." (Alexander, "'Witches' get police

protection.") Village males usually carry out the murders and other acts

of terrorism. But as in the European case-study, patterns of gossip and rumour

are central to the process -- and to shielding the perpetrators from justice.

South African police inspector Matome Mamabolo reports: "If someone is

accused of murdering a witch, the community tends to support them by supplying

money for an advocate when the case comes to court. There is a solidarity there

-- after all, that person is accused of ridding the village of a witch."

(Quoted in Alexander, "'Witches' get police protection.")

Much the

same pattern is evident in Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and Kenya, although the gender

of the victims may be more even. In August 1999, Paul Harris of the Sunday

Telegraph reported that

Lynch mobs have killed hundreds of Tanzanians whom they accuse of witchcraft as black magic hysteria sweeps East Africa. Most of the usually elderly victims have been beaten or burnt to death by gangs of youths. Some old women have been singled out simply because they have red eyes -- regarded as a sign of sorcery by their assailants. The condition is actually caused by years of toiling in smoky kitchens cooking family meals. ... Police say 357 suspected witches have been killed in the past 18 months, but the Ministry of Home Affairs believes that the true figure is much higher. A departmental survey said as many as 5,000 people were lynched between 1994 and 1998. (Paul Harris, "Hundreds burnt to death in Tanzanian witch-hunt," Sunday Telegraph, August 22, 1999.)

In Zimbabwe,

as in neighbouring South Africa, the witch-hunts also seem closely related to

"the black market demand for human body parts, which are used in making

evil potions." The upsurge in such practices, the ritual murders they

require, and the vengefulness that results against accused "witches,"

are all linked to the country's precipitous economic decline. "It's

obvious the cause is economic," says Gordon Chavanduka, head of the

Zimbabwe National Traditional Healers Association (which counts 50,000

members). "The worse the economy gets, the more political tension there is

in society, the more frustrated and frightened people get. They turn to

witchcraft to gain riches or to hurt their enemies." (Neely Tucker,

"Season of the witch haunts Africa," The Toronto Star, August

1, 1999.)

In the

Kenyan case, as was also true in a handful of European countries, the

witch-hunts appear predominantly to target males. A British sociologist, J.F.M.

Middleton, records the conviction of the Lugbara tribe of Kenya that

a witch is a man [emphasis added] who perverts a mystical power of kinship for his own selfish ends and is therefore an evil person. Witches in general are given both physical and moral attributes: a witch has greyish skin, red eyes, a physical deformity; he may travel about upside down; he is bad tempered, secretive, petty and jealous; he is thought to practice incest and cannibalism. The distinction between witchcraft, a mystical activity, and sorcery, the use of material objects, was widespread in eastern Africa, Dr. Middleton said. When, as in Lugbara, the basic principles of organization were unilineal descent and seniority by generation it would be expected that men were believed to practise witchcraft, whereas women should have the less important role of sorcerer. ("How to recognize witches," The Times [UK], September 5, 1997.)

In Kenya in

1993, killings among the Gusii tribe were occurring at the rate of one a week.

"In most cases ... village mobs several hundred strong locked the victims

inside thatch-roof houses and set them on fire. ... According to tribal elders,

the Gusii have always executed people found to be witches. Sanslaus Anunda, a

99-year-old tribal elder, said that during his youth, villagers had a foolproof

method for determining guilt. The most respected men in the community would

call a meeting. Next, they would smear local herbs on the hands of the suspect

and that of a second, innocent man [emphasis added]. Both men would be

ordered to dip their hands into a pot of boiling water, then return in five

days. If the suspect was a witch, burns would appear on his hands. However,

Anunda insists, the innocent man's hands would remain unscarred." (Tammerlin

Drummong, "Kenya: Dozens die in witch hunts," The Ottawa Citizen,

August 28, 1993.)

A trend of

predominantly male victimization may also be evident in West Africa, where a

bizarre wave of accusations of "penis-snatching" has come to light.

The Reuters news agency reported in 1996 that "eight men in Accra, Ghana,

were accused of using witchcraft to snatch penises. Their motivation was

allegedly to return the sexual organs in return for cash. Mobs attacked them

... two died and six were seriously injured. The police examined all the

alleged victims and found their genitals intact. ... [But] the 'victims'

believed that sorcerers only had to touch them to make the genitals shrink or

disappear completely." ("'Witches' steal penises in Ghana,"

Reuters dispatch, January 17, 1996.) D. Trull reported in 1997 that "the

killings of alleged 'penis snatchers'" had been reported "along the

west coast from Cameroon to Nigeria." (See Trull, "Witches

Protection Program".)

Some of

the thousands of

Congolese children expelled from

their homes for "sorcery."

Other reports of

witch-hunting vigilantism have come from Congo, where "The Congolese Human

Rights Observatory ... announced that more than 60 people had been burned or

buried alive since 1990 -- including 40 in 1996. The victims were accused,

often by members of their own family, of being witches." (See "South

Africa Witch Killings", citing Reuters dispatch, October 2, 1996.) In

the neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Zaire), some 14,000

children in the capital, Kinshasa, alone have been accused of sorcery and

expelled from their homes; "the unlucky ones are murdered by their own

family members before they escape." (See Jeremy Vine, "Congo witch-hunt's child victims", BBC News,

December 22, 1999. For a recent report on accused child witches in Congo, see

James Astill, Congo casts out its 'child witches', The Guardian

(UK), 11 May 2003.)

Other reports of

witch-hunting vigilantism have come from Congo, where "The Congolese Human

Rights Observatory ... announced that more than 60 people had been burned or

buried alive since 1990 -- including 40 in 1996. The victims were accused,

often by members of their own family, of being witches." (See "South

Africa Witch Killings", citing Reuters dispatch, October 2, 1996.) In

the neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Zaire), some 14,000

children in the capital, Kinshasa, alone have been accused of sorcery and

expelled from their homes; "the unlucky ones are murdered by their own

family members before they escape." (See Jeremy Vine, "Congo witch-hunt's child victims", BBC News,

December 22, 1999. For a recent report on accused child witches in Congo, see

James Astill, Congo casts out its 'child witches', The Guardian

(UK), 11 May 2003.)

================================================================

To leave the list, send your request by email to:

wunrn_listserve-request@lists.wunrn.com. Thank you.